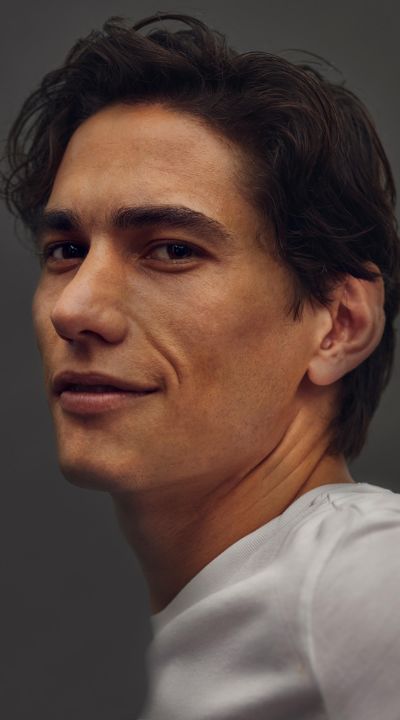

Rising Star: The irresistible charm and captivating talent of Enzo Vogrincic

Tina Kovačiček

February 27, 2024

Tina Kovačiček

February 27, 2024

After closing the Venice Film Festival last year and being showcased in cinemas worldwide, it achieved streaming fame at the beginning of 2024 on Netflix, becoming one of the biggest hits from a non-English-speaking region. We’re talking about the film Society of the Snow by Spanish director J.A. Bayona, which has been constantly talked about lately. Most recently, it has been nominated for the most prestigious film award, the Oscar, in the category of Best Foreign Film and for Best Makeup and Hairstyling. The film brings us again the story of one of the most incredible plane crashes in history (first adapted as the movie Alive in 1993), when a plane carrying a rugby team, family, and friends of the players along with the crew from Uruguay to Chile crashed in the Andes in 1972. In the merciless mountain snow conditions where they spent a little over two months, 16 passengers survived, a feat considered a miracle to this day. The film assembled a brilliant team of actors from the Spanish-speaking world, mostly newcomers. One of them is Enzo Vogrincic, whose connection to this part of Europe is evident. But besides that, Enzo is currently on the radar of global media as a name to remember. He revealed more about himself, what it was like to work on such a demanding film production that launched him into the cinematic orbit, and what he shares in common with Numa Turcatti, the last deceased in the tragedy he portrayed in the film. We caught him somewhere in flight between Europe and America, and we must admit, the way of thinking of this thirty-year-old charmed us. Enzo’s time is arriving.

Hi Enzo, how are you and where are you currently spending your time?

Interestingly, I’m currently on a plane. Lately, my life revolves around airplanes. Yesterday was the Goya Awards ceremony, and already at 6 in the morning, they picked us up to go straight to the airport in Madrid, and now I’m traveling to Los Angeles. I’ve been invited to a private lunch with all the Oscar nominees. It’s an interesting fate. And again, as so many times recently, I must be in the skies.

You’ve always wanted to dedicate yourself to acting, starting on the theater stages in your native Uruguay. What was that role that shifted you to film, and how did you adjust to film acting? Do you see a difference between theater and film, and do you plan to keep both?

Always, or at least almost always, there was a moment when I as a child was convinced I’d become a spy, yes, a real secret agent. I wasn’t sure how, but I knew two things; first, that I had to go to the United States, of course, and second, that I needed spy training. I vividly remember devising training sessions in the backyard where I’d spend the entire afternoon playing or, more precisely, training to become a professional spy. When my parents asked what I was doing, I’d convincingly lie that I was playing something because, of course, a spy never reveals his identity. Even then, there was something in that child’s play where today, as an adult, I see acting as an integrated part of myself. Keeping a secret and not revealing it is acting. Thinking of yourself as someone other than who you are, is acting. Preparing for that specific profession of a spy and realizing I needed training, is also preparation for an actor. Over time, I still find traces of early traits where acting, as a game, was already something natural for me. The next memory is tied to the moment I first experienced theater. I remember sitting with my elementary school peers in the theater, before the start of the show, I was as nervous as if something important was happening. As soon as the stage lights turned on and the huge red curtain was lifted, I was immediately transported to another place, I vividly remember my heart pounding fiercely.

Only at 15 did I realize that acting was a profession I could dedicate myself to, but of course, in Uruguay and for me, a child born in a context of an unfavorable or somewhat forgotten neighborhood, it was hard to project myself as a film actor or at least that idea was impossible to me. At the same time, cinema didn’t interest me at that time, so theater became my goal. I explored further; I found out I had to train at EMAD ( Escuela Multidisciplinaria de Arte Dramatic ), attend lectures from Monday to Saturday for 6 hours a day, I had to pass an entrance exam, and there were only 20 places in the class. My parents asked me what Plan B was if I didn’t pass the entrance exam? “There is no Plan B,” I told them. For me, there was never a doubt, there was no other option but to dedicate myself to acting. And over the next four years, I fell more and more in love with this profession. From the second year, I started working professionally as a guest actor at the Comedia Nacional theater in Montevideo, simultaneously discovering the pleasure of devising shows with friends. It was pure improvisation. Many hours spent in rehearsals, without finances, and with a small audience, usually, only friends and family would come. Theater without profit, just a dedication to acting.

Films came later, gradually and somewhat accidentally. Initially, there were certain opportunities to participate in student short films. UNPAID always was written on the poster they would stick on the EMAD’s door, but that was never important, I was already accustomed. From recommendation to recommendation, I came to shoot a professional short film Yí (el río que no se corta), then to participate in the film A Twelve-Year Night by director Albaro Brechner, and after some time, to my first leading role in the film 9 by Nicolás Branco and Martin Barranchea. During this time, I realized the difference between theater and film. I realized I could break the limiting ideas of myself as someone who couldn’t act in films, that I wasn’t convincing, that my theatrical acting was too exaggerated for the camera. But still, something worked. In the end, I conclude that theater and film, in their vast differences, are complementary. One strengthens characteristics the other does not, and vice versa. Comparing them, I learn about film by doing theater and about theater by doing film. I couldn’t leave theater as much as I wanted. What is clear is that theater is a journey with friends, while friends in film are made along the way.

In 2021, your first leading role was dedicated to Christian Arias, a successful Uruguayan-Argentinian soccer player. Interestingly, considering your father was a soccer player in Uruguay. Tell me more about that.

Once a director told me something that stuck in my memory, “One does not choose characters, characters choose him.” At that moment, I didn’t fully understand what she meant, but over time it made sense. When a person deeply connects with a character, there’s something in that character that reminds you of your own self before you start recognizing yourself in it. In the case of Christian, the story is fantastic. My father experienced a moment of fame as a professional soccer player, and as a soccer lover, he took me to practices in different teams from my 4th to 12th year. He tells me how I immediately entered the game on the field and very quickly started mastering the sport. I, unaware of it, simply never wanted to play soccer. Today I enjoy playing with friends, but generally, I’m not interested and don’t follow it. What I could never tell my father is that I’m not interested in soccer at all, I didn’t want to play, every time I was grateful when the training was canceled, and even more so when the match was canceled. When the script for 9 came, I knew it was for me. Christian, a professional soccer player who doesn’t know if he wants to play soccer because he didn’t personally choose it, but had to play because his father led his career. It was wonderful to live through this character to somehow express that deep desire, which I could never publicly admit, the desire to no longer want to play. Characters and acting give you the opportunity to discover yourself, to examine and deepen your insights about yourself. This is one of the reasons I fell in love with this calling. When Christian finally manages to tell his father that he no longer wants to play, and when my father came to the cinema to watch that film, for me, a liberating cycle was completed.

Your surname Vogrincic is particularly interesting to us, you have Slovenian roots. Can you briefly tell us more about your family history?

I should explore more about it, it seems like an interesting story. What I know is that my great-grandfather came by boat from Slovenia to South America, during World War II. He came with his whole family including my grandfather who was about 2 years old at that time. They planned to go to Argentina, but for some reason, they decided to continue their journey by boat to the next destination – Montevideo, Uruguay.

Are you connected with your Balkan roots? Do you visit these parts or are you only still planning to?

I love the word Balkan, it stirs in me a desire to connect. But the truth is that to this day I don’t know much about Slovenia, it seems like a beautiful place that every time I return to Europe motivates me to get to know it. I would probably start with Murska Sobota, where my family comes from. Maybe there I find something for myself.

What was it like growing up in Montevideo, what do you remember, what marked your childhood there?

Montevideo, like any other city, has its zones. Neighborhoods are very different and in each one lives and grows in a different way. I grew up near the Gruta de Lourdes shrine, which is located on the outskirts of Montevideo and within the area the media calls the Red zone. The name indicates that it’s a marginal area, and everything that is marginal is always connected with danger, and that for those who don’t live there, of course. I grew up with limitations and shortages such as denied opportunities and possibilities which over time can also create a mental burden that is hard to let go of. The world from there always seemed like everything works against us. However, I remember as a child I was always aware of this. My older brothers often complained that in a job interview they have to invent where they come from because if they mention the Red zone, they will be rejected. On the other hand, Uruguay itself is a modest country with few inhabitants and almost no tourism, where going out on the street means that you will probably meet someone you know or meet a person with whom you have mutual acquaintances. This makes Montevideo a tiny town. It’s a wonderful peace that attracts me more and more as I travel and return to it, increasingly appreciating the way we are connected there, warm, close. It seems to me that we forget that we are all somehow neighbors there. Also, growing up in a place where progress is complicated always leads you abroad, far from the place you come from and where there are better opportunities for you.

However, I remember learning about the geography of Uruguay and its characteristics at 10 years old, when the teacher mentioned that in Uruguay we don’t have earthquakes or volcanoes, nor tornadoes, monsoons, or tsunamis. I remember, looking at the world map, thinking: What luck to have been born here.

You are currently experiencing the peak of your career, I would say. The film Society of the snow is being talked about worldwide. What has changed in your life recently?

My life has revolved around this project for a long time, practically from its inception. Going on such a long journey because of filming already implies changes. For starters, it was the first time I had left South America and since then everything has become more intense. After the premiere of the film, I had a moment when something that had been a part of me for so long became public, and people have the opportunity to emotionally attach themselves. Likewise, you start building a version of yourself that is somewhat fictional, and that’s what I’m currently discovering. People know me through Numa, and it mixes with who I really am. It’s as if it’s a blend of both personalities; people who call me Numa, people who call me Enzo. What’s a bit stranger is that I start to rebuild my intimate spaces in public, and that line is somewhat blurred somewhere. In Uruguay, the media follows me, but luckily people there are generally calm and not intrusive while in Madrid the whole media story is more intense. It’s strange to experience ending up as a character on a T-shirt or mug or even a life-size cardboard cutout. That media noise is so loud that I start to see myself from the outside. I know myself and believe in who I am, but when that external image surpasses me, it all becomes something else. My life is gradually changing, and the change happens before I even realize it has just occurred.

How challenging was it for you to prepare for the role of Numa Turcatti, the last deceased who almost saw salvation in the mountains along with 16 others who were all on the brink of strength after 72 days spent in incredible winter conditions among the mountains. The real story of surviving this plane crash is more than fantastic and almost surreal.

Already transitioning from theater to film, unexpectedly participating in a mega-production in the middle of the mountains is a scenario that’s impossible to predict. Fortunately, during 7 months of auditions and 2 months of previous rehearsals we went through before filming, I built the character of Numa and prepared for what was to come. The rest, as always in my life, is learning through work, something in which I also feel very comfortable. This filming brought me a lot of practice and experience. We shot for 147 days, with a team of top professionals, and also the story challenges you on a physical level, and acting becomes part of you and your real body. (Note: Enzo had to lose 23 kilograms in just a few months for the role). Cold and hunger are elements that make everything more real. You actually carry the character in your own body. My biggest challenge was to fight my own mind. To conquer the constant idea that often lives in me and tells me deep from within: They made a mistake, and they’ll realize it wasn’t me. That idea, that impostor syndrome that is so common in this profession, over time became my motivator, kept me going, didn’t allow me to give up because if I gave up, they’d notice. Luckily, they were wrong until the very end and didn’t fire me. That thought always drives me to immerse myself in the role to the fullest.

Preparing for the role, you had the opportunity to talk with the actual survivors. How did you experience that, and how did it help you for the role?

Meeting them in person brought the story down to something real and concrete, and that’s a good thing. When you first hear about what happened back then, it seems like a myth that slowly disappears as you talk to them and becomes a story that really happened. I first met them before filming, and then later we traveled together because of the film’s promotion at festivals. They are people who have a very strong and spiritual life experience, they teach a lot without being aware of it, they talk about life through a special perspective because they’ve lived through it, and they’re here today, have families, and lives that have continued. For embodying Numa, it was essential to meet them. I always say in interviews that the aggravating circumstance with Numa is that he was someone real, and I don’t have the opportunity to meet him and get closer to him. Therefore, I must build him from the memories of those who knew him, his brothers, friends, and also survivors who spent 60 days in the mountains with him. With all the people we talked to about Numa, I found common things related to him being an exceptional friend, his integrity, his strength, virtues that everyone unanimously highlighted. And that’s rare, for all survivors to agree on something.

Those who survived are not just those who crashed in the plane in the mountains, they are today bigger people than that, with real lives they continued to live. Still, that story follows them all their lives, and I see that most of them still feel it. Even though things are overcome, they also follow you.

What was it like working with director J.A. Bayona? What did you learn?

A better question is what didn’t I learn? It was exceptional to work with him on the project, it was like taking an accelerated master’s degree in film. He made a lot of effort to eventually make my job easier. Without a doubt, he is intense, goes so fast that he forces you to try to keep up. He is a director who leaves no aspect to chance, but takes care of everything. I saw him come onto the set excited after discussing with the designer and in the end painted the plane with blood because he noticed that detail was missing. At the same time, he listens a lot on set and takes ideas from everyone for making each frame. He works hard and improvises, has both aspects, that’s a virtue. You also have to be brave to put such a huge set at the disposal of creativity and the spontaneous moment. After we practiced 2 months every day, had the script and changed it after rehearsals, we saw him coming to the set with a new printed shooting plan, and new scenes he sketched the night before after seeing in the editing that something was missing. This as an actor forces you to be available and to trust him.

Are you going to the Oscar awards ceremony?

It seems that I am.

What are you currently working on? What are your plans?

Currently, I’m enjoying every additional outing with the film. Until recently, I only suspected that all of this could happen, and since I don’t know if I’ll have such opportunities again, I decided to free myself from every obligation and be available to follow the film wherever it goes. Currently, that’s the priority and there will be time to think about what I will dedicate myself to next. Luckily, I’m not someone who is anxious, on the contrary, I really like when time passes between two characters. Something changes in the person during that period, and that’s good to listen to for this acting call. We’ll see what’s next.

Netflix Studios

When you’re not acting, what do you like to do, what occupies your thoughts, what do you think about?

So many things… By nature, I’m curious like all people, I believe, but above all, I seek creativity in everything I get my hands on. I have several ideas that I’m currently working on… I’m writing a book, some kind of reflective diary of filming, I don’t know if it will ever be published, but I’m working on it. Every experience I like to bring down to something more concrete.

On the other hand, I’m building a mini theater 75 cm in length x 40 cm in width x 65 cm in height. It’s like a realistic model of a theater where I want to show the experience through sound, light changes, and scenography. It’s a kind of tribute to theater, it’s hard for me to explain it just with words, but it’s something that combines handwork and sound assembly, and I really like that. I always think of theater, I’m developing some experimental theater projects for just a few viewers, two to three only, which I plan to make as an experimental prototype at home. Sometimes I paint, sometimes I design furniture in 3D (my hidden geeky side). I like to hang out with family, friends, I love my plants, photography…