They can be hilarious and sardonic using humor as a tool for resistance. They take the system and smash it down to the pieces. Or go in the opposite direction and use sensuality to disturb expectations. After her book “I am Jugoslovenka”, an unique story of women’s resistance through the intersection of feminism and socialism, Jasmina Tumbas comes with a new essay where she turns to the feminist figures of Jugoslovenkas artists active in the diaspora today.

Repugnant in the artifice of her irresoluble multiplicity and contradictory manifestations over decades of time, disparate geographies, and clashing feminisms, the figure of Jugoslovenka, as I theorized her in my first book, was once compared to a frankensteinian monster. In feminist, queer, and trans theory, as well as popular culture, the monster has long been reclaimed as a magnificent icon of resistance, threatening those repressive patriarchal regimes that seek to govern gender, sexuality, bodily autonomy, and communal life.(1) To quote gender studies historian Susan Stryker’s exquisite theorization of the creature’s fate as analogous to her trans experience: my exclusion from human community fuels a deep and abiding rage in me that I, like the monster, direct against the conditions in which I must struggle to exist.(2) At the time when Stryker launched her critique in the U.S. academic and medical-psychiatric context in 1993, Socialist Yugoslavia was disintegrating in civil-war, engendering generations of disobedient misfits who to this day haunt their makers; this essay turns to Jugoslovenkas active in the diaspora today, whose art reveals powerful elements of a monstrosity inherited from the failed socialist state that birthed them, and is infused by the Western democracies that seek to tame them.

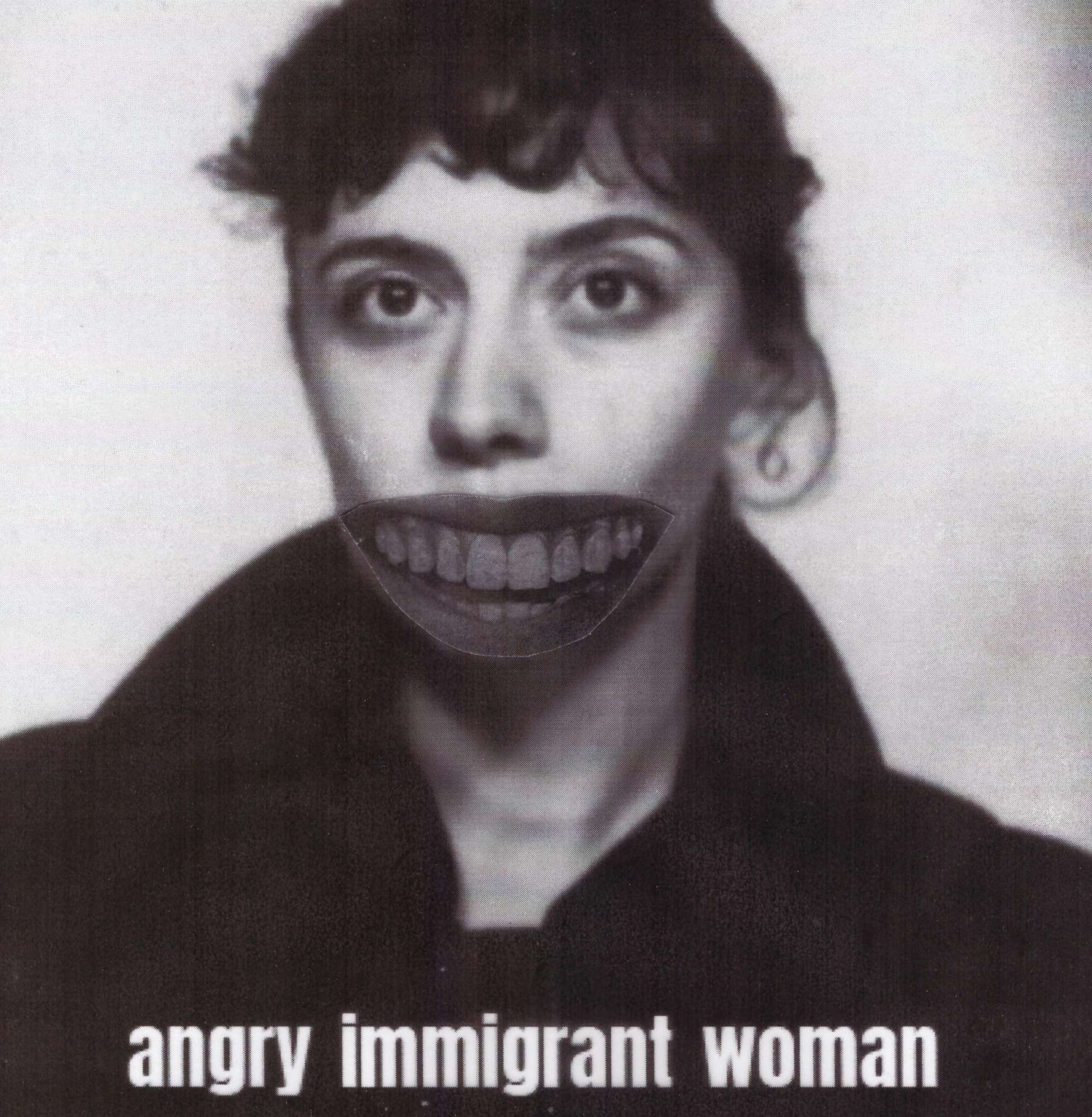

Feminists of the Yugoslav diaspora have been at the center of powerful ideological clashes in some of Europe’s most important capitals for contemporary art; as I am writing this text, writer Lana Bastašić has terminated her contract with the prestigious German S. Fischer Verlag to protest the censorial crackdown on pro-Palestinian sentiments in Berlin(3); there, she is joined by many others in her criticism of Germany’s cultural elites and institutions, including Hana Ćurak, founder of the well-known multimedial and collective platform, It’s All Witches (Sve su to Vještice), which focuses on creating a counter-archive of Yugoslav feminist history, with the aim of radical intervention into possible feminist futures.(4) Hilarious and sardonic, anger and humor play equally important roles in feminist and diasporic relief needed for shaping such alternative futures, especially for foreigners in Germany. Mila Panić’s self-portrait Angry Immigrant Woman foregrounds the grotesque force of compulsory assimilation in the perfect smile—afforded to the privileged—fixed on the artist’s own mouth, muzzled, her wrath spilling over the edges of her containment. Commanding strength from such disfigurement marks her audacious speech; as a stand-up performer, Panić frequents art and comedy venues alike, cunningly sizing up her audience and presenting herself as a barbaric other from a disgraced region of the Balkans: …While other kids were playing with Legos, I played with leg bones. They were not always from animals. It was war in Bosnia, what did I know? The game was to collect the set. It’s fine guys, you can laugh. Thanks to me my family is finally together. Pointing at the painful aftermath of war, leaving families desperate to find the remains of their loved ones, Panić adds: It was a very hard game. My village was a frontline in the war. Do you know how hard it is to tell apart Muslim and Serbian bones?(5) As her audience laughs, many of us from the region grimace with searing pain of grief beneath our deep but discreet gratitude for her courage.

Gratitude, when expected from others, however, may shackle its bearer; those who gain mobility and access to the elite contexts of art and the academy through merit and good foreigner legibility know this too well. Gratitude can eat the heart out of you, working-class feminist writer Dorothy Allison once remarked, because it forces one to surrender to the certainty of one’s status in society as lesser, or as that of a beggar.(6) Resisting this indignity marks Selma Selman’s extraordinary ability to talk back to the artworld and expose the exploitative regimes that feed the elites who run it. My parents are not rich like yours, she writes in one of her Letters to Omer.(7) In another, she writes I know no one deserves my gratitude.(8) A formidable pride underlies Selman’s unrelenting commitment to turning the social economy of expected submission on its head: instead of obedient appreciation to the West, the artist forces her audiences to their knees in astonishment of her promethean expertise—bequeathed to her by her family—of dismantling discarded machines and extracting precious capital from the trash laid at her feet.(9)

Šejla Kamerić and Aleksandra Vajd, Review, 2023 Part of Darker, Lighter, Puffy, Flat at Kunsthalle Wien, curated by Laura Amann (November 29, 2023–April 14, 2024)

Intrigued by erotically charged bodies morphing and colliding in Šejla Kamerić and Aleksandra Vajd’s collaborative magazine Review(10), currently exhibited at Kunsthalle Wien, viewers in Vienna kneel to touch its alluring pages, perforated and affixed by metallic poles onto a pedestal and distributed on the gallery floor. Releasing the pressure of corporeal cohesion in copious close-ups of bare skin colliding, fingers entering mouths and other orifices, the confines of the self dissolve: things appear upside down and diagonal, genitalia are interchangeable, and erotic desire permeates everything, including inanimate objects. Vulnerability, sensuality, and connectivity disturb expectations for diasporic integrity, in both of its meanings: resistance lies not in bodily autonomy but in the artists’ hunger for fusion with the world, here too spilling over the edges of moral containment, such as ascribed heterosexuality, professional boundaries, and expected victimhood, so readily projected on women from war-torn contexts. In the words of Bikini Kill: As a woman I was taught to always be hungry. Women are well acquainted with thirst. Yeah, we could eat just about anything. We’d even eat your hate up like love.(11)

Collective resistance in lieu of capitalist individualism lies at the heart of Jasmina Cibic’s newest film, Beacons (2023), in which the artist transports her audiences to moss-covered forest and snowy mountain sites that bear Yugoslavia’s histories of anti-fascism and their spectacular monuments. Female protagonists use diverse creative strategies such as dance, Morse-code, light signals, and playing various musical instruments to rehabilitate revolutionary declarations that were originally made in 1985, at the first conference for cultural workers of the non-aligned held in Titograd (today: Podgorica).(12) These messages of resistance are broadcast via megaphone at the beginning of Beacons, by a lone horse rider filmed in the forest of Jelovica above Dražgoše, a Slovenian village that was burned to the ground by the Nazis in 1942. Reviving the memory of what the artist calls “ancestral resilience,” we witness a chain of skilled female messengers inhabiting the singular task of transcending vast landscapes—ideological and real—with their craft. They are the beacons that transcode the unfulfilled promises of the past, culminating in a mesmerizing speech that emphasizes the liberation of workers globally. Its messages are everything but outdated, especially considering the difficult state of the world today. Beacons thus becomes a powerful analogy for an emerging feminist Yugoslav diaspora in the arts: dispersed and fragmented as they may be, the artists share robust albeit diverse commitments to feminist resistance; framed as a collective body—emerging from the unique legacy of Yugoslavia across different generations and geographical boundaries—they are a monstrous force of beauty, or in Cibic’s words, they are breaking free through empires of defiance.