Monsters have always been diagnostic beings. In The Philosophy of Horror, Noël Carroll describes them as “categorically interstitial,” while Mary Douglas places them, in Purity and Danger, into the realm of “matter out of place”: forms that provoke disgust because they blur the boundaries on which social order depends, giving shape to our anxieties through flesh, teeth and claws. They live in the cracks of cultural taxonomy, beings with no fixed place, feared not for what they are but for how they destabilize the borders that keep our worlds “under control.” Even the word itself reveals its function. It comes from the Latin monstrum, a sign or divine warning, from monere, “to show.” Monsters were never just beasts. They were messages, animated signs of cultural disturbance.

In my clinical work, as a therapist in training, I’ve come to think of the monster as the parts of ourselves we deny, neglected places that keep asking for integration. In my work as a journalist and writer, which in its commitment to pattern-seeking doesn’t differ much from therapy, the monster takes on a different shape. It becomes the body of everything unsaid, the parts of the story we exclude, impulses or realities we mark as wrong or taboo. In both cases, the monster exposes refusal. It reveals the gap between what is allowed into discourse and what gets pushed out.

Dracula: A Love Tale, Director: Luc Besson

With the renewed rise of the monster canon, from Besson’s Dracula to Del Toro’s Frankenstein, and in the shadow of last year’s Nosferatu and the Oscar-winning body-horror film The Substance, it’s clear that the monstrous remains one of our most persistent cultural languages. Instead of functioning as simple terrors, their gothic anatomies read like questions. They ask which parts of ourselves and others we’ve declared unworthy.

In that sense, meeting the modern monster isn’t just meeting a creature, but a reflection. This is what gives Jacob Elordi’s performance in Del Toro’s adaptation its pull. At first glance, the eleven hours of pale makeup didn’t convince me. Elordi looked less like a frenzied, subhuman Frankensteinian creature and more like someone who went too far with a Halloween makeup tutorial. But then it clicked. That was the trick. Del Toro has always been a master of creating monsters we feel for. From the aquatic saint in The Shape of Water to the grotesques of Pan’s Labyrinth, his creations carry something deeply human in both form and desire. While other horror narratives insist on the anatomical “otherness” of their monsters, Del Toro insists that we recognize ourselves in his. Across Frankenstein adaptations, from James Whale’s stiff, thick-necked creature of 1931, through Branagh’s operatic 1994 remake, to the polished but emotionally hollow reboots of the 2000s, the monster was treated as a clinical experiment or gothic mechanism, far removed from the human.

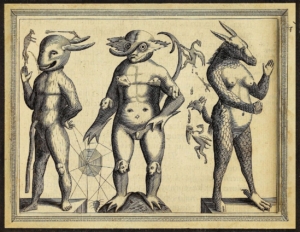

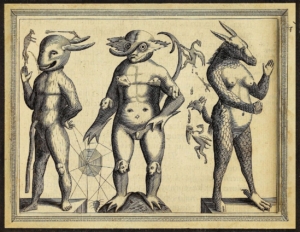

1665. edition of Fortunio Liceti’s book, De Monstris.

Perhaps, paradoxically, the almost-human quality of figures like Frankenstein’s creature exposes the limits of our imagination. We build beings in our own image because what is truly “other” lies beyond our reach, leaving monsters to carry our distorted impulses. In Del Toro’s Frankenstein, the creature’s monstrosity becomes a moral accusation. Nearly every human he meets, from shepherds to villagers to Victor Frankenstein himself, reacts with instinctive violence. They recoil not from his nature, but from what he reveals: the fragility of our claim to goodness. Meanwhile the creature, assembled from death, grieves with a sincerity the living characters cannot muster. His longing for closeness is painfully human. Del Toro flips the myth. The monster is not the unfeeling one. Humanity is the one incapable of compassion.

Related: After Frankenstein, we’re rediscovering Oscar Isaac’s brilliant early roles

That inversion, where grotesque bodies hold the moral center, feels distinctly modern. In a time when identity is built through optics, the monster becomes a figure of honesty, a being unable to hide its difference. As Charlie Fox writes in This Young Monster, the monstrous is not a deviation from the human but its natural extension, a figure exposing how arbitrary “normal” has always been.

The archive of monstrosity, from classical depictions of cyclopes and sirens, to medieval bestiaries, witch-hunt pamphlets and reports of “monstrous births,” to Victorian freak shows and today’s body-horror renaissance, forms a continuous genealogy of the monstrous. It’s an evolving lexicon of everything that cannot be absorbed into the category of human. Monsters are invented whenever a culture needs to discipline differences. In early modern Europe, the monstrous body served as a warning: a deformed infant signaled divine anger, a rupture in the moral order. Over centuries, the monster acted as a cultural disposal site, a container for what we refuse to integrate. That logic hasn’t disappeared. It has only moved inward.

Johann Heinrich Fussli, The Nightmare, 1781.

My first encounter with monsters, like most children, was the idea of something hiding under the bed. A shoebox-sized space full of exiled artifacts. Those were the original monsters: lost, forgotten, repressed things that hovered in the shadows. Heidegger gives that childhood intuition a philosophical outline. In Being and Time, he writes that Angst is not fear of one specific thing but the moment when the familiar structure of the world, the bed, its frame and the neat order we rely on, slips out of joint. The bed is meant to be a place of safety, a stable platform that holds the self together. Everything that falls beneath it becomes instantly alien. That dislocation is what makes the space monstrous: a miniature theater of the unassimilated, a storage zone for what has slipped out of the net of order. Heidegger, following Freud, calls it the unheimlich: when what was once homely becomes strange. The monster isn’t a horned creature lurking in the dark. It’s the dark itself, the painful awareness that something is present where it shouldn’t be, disrupting the assumed coherence of the world.

Looking at popular culture, it seems we never outgrow the monsters under the bed. We just move them. Into the psyche, into pop culture, into figures we fetishize or demonize. Into each other, and into the world, again and again, until their origin blurs. Until we forget that we banished them, holding on to the fantasy that we look nothing like the creature we made. Frankenstein’s arrogance is simply the earliest expression of this logic. Today the monstrous emerges wherever human control slips: in artificial intelligence, biotechnology or algorithmic systems that exceed the intentions of their makers. Fargeat’s The Substance visualizes that refusal with surgical clarity. The monster is no external sign but a warning about the consequences of our own overreach.

If we return to the warning embedded in the word monster, it becomes easier to keep playing the comforting fiction that we look nothing like the forms we create. It’s almost too obvious to say: what makes a monster is its maker, in full Mary Shelley fashion. Maybe monstrosity doesn’t arise from creation itself, but from the refusal to acknowledge that creation. In this sense, the monstrous is less a being and more a consequence, an image of our psychic rejections laid bare for the world to see, inviting both analysis and further escape.