When Croatian director Nebojša Slijepčević’s film was nominated for an Oscar earlier this year, I felt it as a quiet victory for all of us who “couldn’t keep silent.” In just thirteen minutes based on real events, it confronted us with questions of responsibility: what do we do, or fail to do, when we witness wrongdoing? It is easy to be righteous when there is no risk, but when danger draws near, do we remain upright? A story drawn from wartime past illuminated moral dilemmas that still live with us, and along that path, each in its own way, the region’s candidates for the 98th Academy Awards, to be held in March 2026, has set out.

From the suppression and release of women’s voices and bodily autonomy, to the relationship between humans and nature under threat of destruction, to the scars of societies sliding into authoritarian and nationalist ideologies, every film in the race testifies to what I believe, almost utopianly, to be true: that art today has an obligation to be engaged. The fates of their characters show how personal courage, resilience, and compassion are tested under systemic pressure, exposing the weaknesses and absurdities of entrenched patterns, and the individual’s power to preserve humanity in spite of them. Some invite us to become authors of our future again, others remind us to protect the vulnerable and step away from every kind of division, and still others tell fable-like stories of healing the soul in a consumerist world. Each one brings back that fragile, electric, and necessary spark of meaning.

„Kaj ti je deklica”, Urška Đukić | Slovenija

In her first feature, Little Trouble Girls, Urška Đukić captures moments of growing up through a subtle yet subversive exploration of sexuality. Between two students in a Catholic choir—Lucija (Jara Sofija Ostan) and Ana Marija (Mina Švajger)—an attraction grows as they meet every weekend in a rural monastery. “The inspiration came while I was watching a concert by a Catholic school choir. The girls sang an old Slovene folk song with such force that I cried. There was something extraordinary in those voices of young girls on the verge of becoming women. It felt powerful and important, especially given how often women’s voices have been silenced. I remember three priests in the audience, equally moved, and the scene felt unusual: patriarchal, celibate men listening to voices filled with female energy. That image was so enigmatic I knew I had to explore it,” she says. “I followed that choir for a while, observed, and that became the seed of the script. I started from the question of the female voice—how it has been repressed, and how it can be uplifted. That led me to the body, sexuality, guilt, shame, spirituality, and the long path to one’s own strength.” Not just any voices, but voices in unison, which gives the film a potent sensory charge.

It began with self-reflection. “As a girl I often felt guilty about my impulses. My family wasn’t very religious, but my mother still passed on traditional Catholic ideas of what a ‘good girl’ should be. It took years to see how limiting such ideas are, especially around the female body and sexuality.”

Lucija, the protagonist, is a quiet, pensive girl from a religious family. She is drawn to Ana Marija, a charismatic, confident peer who captivates others with her cynical view of the world. Lucija’s innocence amuses her, but she recognizes in Lucija a calm and confidence that comes from within. Attraction does not always mean a desire for an act. Sometimes we are drawn to something another person has and we lack. That, too, is a form of sexual energy. Lucija is pulled toward something she does not yet understand but must follow to grow, like contradictions yearning to intertwine.

On the surface, Kaj ti je deklica is a story of queer desire awakening under the watchful eye of the Catholic Church. The film resists simple reading. The idea of sexuality as sin is a hidden form of control, one that cuts us off from our own source of strength. The connection between Lucija and Ana Marija may be brief, but through it both touch a deeper truth that reunites body and soul, long divided by dogma. “The film tells us how important it is to feel our bodies more deeply and to follow our own inner guidance rather than blindly obey social instructions that history shows are often senseless and limiting,” Urška concludes.

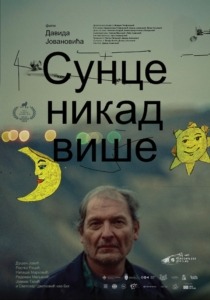

„The Sun Will Never Shine Again”, David Jovanović | Srbija

On one side there is life, hard and gray, in a landscape poisoned and dangerous. On the other, spectacular vistas and fantastic micro-worlds the locals have created for themselves. From the first shots it is palpable that The Sun Will Never Shine Again follows an individual who stands against those whose actions threaten irreversible destruction of nature and heritage. The most devastating element is that it is based on real events. Director David Jovanović, inspired by childhood summers in a Bosnian mining village, shot the film in Krivelj near Bor, where mines do exist and expand right up to residential areas. “Involving the people of Krivelj was essential. First, everything they did for us—demolishing, building, cooking, plowing, cutting—and everything they allowed us to do, we could never have afforded. More importantly, their stories and culture shaped the film. Without them this would have stayed a short. I filmed many additional scenes inspired by what I heard and saw. That is why we are now within reach of the Oscars,” he says. Some residents accept the offer to sell their land and leave, hoping to escape the pollution and the tremors from the explosions. The protagonist, Vid (Dušan Jović), is a tough, principled man who refuses to let his way of life fade away, breath by breath. His son Dule (Rastko Racić) looks up to him. Together, they build a greenhouse — for Vid, an act of defiance against the encroaching ruin; for Dule, a refuge for imagination.

The motif mirrors what Jovanović witnessed. “We met people who religiously collect antiquities and say with pride: there are things here that will blow your mind. We met a man who made a small paradise in a grove with a fishpond, and a nudist beach called ‘At The Cheat’ in the middle of a tailings dump. Their worlds are fantastic and surreal.” This is how they survive daily blasts, collapsing houses, black water, withered plants, sick bodies, the total devastation of nature that looks like abandoned planets. A divine figure appears as well, played by Svetozar Cvetković. “When Đorđe and I shot a documentary in Bosnia, researching a world like ours here, we interviewed my grandma’s friend Rađo, who built a little oasis in a mining village. In the middle of that ‘paradise’ he stood before the camera and said, word for word, everything Svetozar says in the film. It was natural to cast him in such a role, since in two of my student shorts he played similar authority figures—Charon and a directing professor.” The film’s visual language, made of long, slow takes, keeps everything in duality: lyrical and raw, defiance and imagination, hope and hopelessness, honor and brazenness. When it was announced as Serbia’s Oscar submission, it was marked as an auteur work with a contemporary and universal theme.

Two things weighed in its favor: the universal story of people and nature suffering at the hands of multinational mining companies across the planet, and the coherence of a tragic story told in a stylized mode of poetic naturalism. Although Jovanović says he does not believe in agitprop cinema, making a film that defends honor, integrity, and common sense in a world running out of breath is the kind of engagement we need.

„Blum: Masters of the Future”, Jasmila Žbanić | Bosnia and Hercegovina

I first encountered this film in late spring at Beldocs in the Battle for Reality section, a selection that probes how we interpret truth and build a shared reality in an era of rapid technological change, rising authoritarianism, confusion, fragmentation, and media overload. After narrative features like Grbavica (2006) and her Oscar-nominated Quo Vadis, Aida? (2020), which exposed Serbian war crimes during the breakup of Yugoslavia, the most acclaimed contemporary Bosnian director Jasmila Žbanić turns to documentary to illuminate an extraordinary figure—Emerik Blum, the engineer and visionary who founded the renowned Energoinvest company in postwar Bosnia and Herzegovina, built on a model of workers’ self-management. Through rich archives and testimonies, the film shows how Blum, in a rural and shattered environment, created a global company guided by a philosophy that now, in capitalism, feels almost utopian. Although it portrays Yugoslavia’s largest exporter, a giant with 42,000 employees and a billion dollars in profit, Energoinvest appears through small, almost family scenes.

For workers it was more than a job: Yugoslav economic structures and Blum’s initiative meant company-owned apartments, seaside cottages on the Dalmatian coast, and annual sports competitions. In contemporary interviews interwoven with archives, Blum appears as a paternal figure, strict but fair and loved. More than forty years after his death, employees still recall his words with nostalgia. The film is a vivid testament to the enduring power of Blum’s vision and a reminder that companies can thrive under models very different from today’s rapacious capitalism. For older generations it is a return to a fairer refuge, and for younger ones a hope that work, knowledge, honesty, and decency pay off if we push back against what we witness, locally and globally. After the premiere, Žbanić paraphrased Blum: “Let us become masters of our future again.”

„Honor”, Nikola Vukčević | Crna Gora

Obraz, or Honor, is multilayered in our culture. It sits at the center of moral and social codes, signaling dignity, integrity, and personal honesty. To lose it is to lose one’s place in the world, the trust of others, and oneself. To keep it is to remain true to one’s principles even in hardship. To stain it is shame, deceit, betrayal, moral fall. In a patriarchal context, especially Montenegrin, where pride and honor are pillars of social order, honor can outweigh life. A word given on one’s honor—stronger than any other obligation in the Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini, which served as law among Albanians for centuries—is the starting point of Nikola Vukčević’s third feature, Obraz (Honor). “I was most interested in the individual who chooses to resist the law of the strong. That was my main motive, while the Kanun in the film is a frame, the cultural and moral landscape that makes the protagonist’s path harder. More than the code itself, I cared about what happens to the individual inside that system, to a man seeking a moral compass as order collapses in the chaos of the Second World War when rules of honor do not hold.

In such a moment, honor stops being tradition and becomes identity, humanity, responsibility. I believe the moment my protagonist makes his difficult choice is what prompts audiences to ask themselves what they would do,” the director says. Set in Montenegro’s mountain regions inhabited by Albanians during the war, this historical drama with phantasmagoric touches follows a clash between an SS unit and one honorable household over the fate of a boy from an Orthodox village who found refuge there. In his community, Nuredin Doka (Kosovar-Dutch actor and director Edon Rizvanoli) is a respected hero and clan representative, a man who honors the code yet can still rule in favor of life. He ended a blood feud with the rival Gjonaj clan and, instead of killing their son, chose to adopt him. During the war Nuredin chooses to stand aside, to survive by hunting with his son Mehmet (newcomer Elez Adžović), unwilling to side with cowardly Nazi collaborators or atheist Communist partisans. “In Nuredin I saw a man trying to reconcile who he is with what is on offer at the cost of his family’s life. His decision to protect a child who is not his, a child of another faith and nation, raises a timeless question:

How far will a person go to preserve moral peace?

The attraction lies in the ancient dimension of a tragedy unfolding on our Balkan ground, where honor, family, and responsibility are pillars of identity. The film doesn’t idealize heroism. It shows how courage and fear, doubt and love, can coexist within a single decision.” The result is not only the portrait of one man, but a reminder of what compels us to protect the vulnerable and preserve our humanity, even as divisions of creed, nation, and ideology persist. Čojstvo — humane virtue — stands equal to bravery.

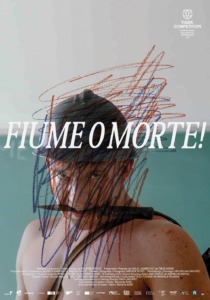

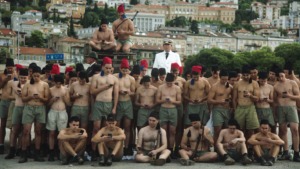

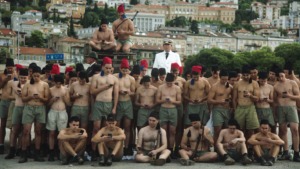

„Fiume o morte!”, Igor Bezinović | Hrvatska

The most watched Croatian documentary of the last thirty years, Fiume o morte! investigates a controversial episode led by poet and nationalist Gabriele D’Annunzio, who in 1919–1920 occupied Rijeka (Fiume) to annex it to Italy. His sixteen-month rule was marked by authoritarianism, militarism, and a cult of personality. The consequences were dire not only for the city but for the world: D’Annunzio’s exploits inspired a young Benito Mussolini. In an era of surging fascism and the far right, Bezinović’s film feels pointed, although the idea predates today’s moment. “I do not remember when I first heard of D’Annunzio, but I remember when he became important to me. In my early 20s I studied philosophy and sociology and read Hakim Bey’s ‘T.A.Z.: The Temporary Autonomous Zone’ from 1991.

There is a chapter about D’Annunzio in Rijeka. I read it several times to be sure it was really about my hometown. Bey calls Rijeka a ‘pirate utopia.’ I hoped he was right because I wanted my city to have that anarchist legacy. Unfortunately, it turned out his theory was not based on serious research but on surface speculation,” the director says. Born in Rijeka, he approached the project “with a personal interest in my city’s history and to understand the present from a new perspective.” The film assembles a vast archive and casts mostly amateurs, locals he stopped on the street to restage scenes from historical footage, laced with lucid humor and self-irony. Young men play soldiers; when he finds a house that used to be the hotel where D’Annunzio slept en route to the city, he persuades the current homeowner to play the maid. Some scenes required a full transformation: a nail salon now stands where D’Annunzio’s favorite tavern once was.

With the owner’s permission, the team rebuilt a replica of the long-gone bar. Crucially, the reenactments do not only show archived events, they repeat the original compositions and camera setups, reconstructing the directing process itself. D’Annunzio’s fanatical nationalism is set against images of today’s soccer fandom—flares, chants, clashes between Rijeka and Split supporters—everyday identity performance that opportunists can turn into a weapon. In one harrowing scene, after a referendum in which Rijeka’s citizens largely rejected annexation, D’Annunzio smashes ballot boxes, beats civilians, and declares his victory. “That obstruction of elections is the most tragic moment for me. I fear that practice, still common after D’Annunzio, where one claims to believe in democracy while mocking and criminalizing it, can only lead a country into ruin,” Bezinović adds. Fiume o morte! shows how easily an ambitious demagogue and his circle can ride a wave of complicity and apathy in a divided society to absolute power.

“We were lucky this film came out when it was needed,” he says.

„The Tale of Silyan”, Tamara Kotevska | Severna Makedonija

Imagine a documentary that is also a poetic meditation on the unbreakable bond between human and nature, love and healing. Tamara Kotevska, best known for her Oscar-nominated Honeyland (2019), now weaves an old folk tale about a young man, Silyan, who becomes a stork after his father curses him for refusing to continue the family trade, with the real struggles of a farmer in contemporary North Macedonia. In Nikola, the head of a farm family under threat, she found a personification of both themes. The Tale of Silyan was the first story my grandparents ever told me, and when I began filming I had no idea I would include it. As a filmmaker who has spent ten years on environmental and migration documentaries, my initial focus was on white storks and how their migration is changing due to new feeding habits and overflowing landfills. But as often happens, the story shapes the author. I was struck by the mirror effect between humans and storks and wanted to show the similarities. After more than a year and a half of filming, when Nikola found an injured stork and decided to care for it, the tale of Silyan returned to my life as inspiration. Watching these two beings share loneliness and give one another meaning, I could not ignore the images I had as a child. It was a symbol made real,” she explains. At first, Nikola’s life seems almost idyllic.

His beloved wife Jana is always by his side in the fields, and they act like teenagers flirting between chores. Unlike Nikola’s son, who left the farm and country in search of an easier life, his daughter Ana and her family remain. Then everything changes when state regulations prevent the family from selling their crops. Tons of produce end up on landfills where they rot and feed storks. In the struggle to survive, Nikola is left alone as family members leave. His fate intertwines with Silyan’s, a lonely traveler who longs for his father, migrates from place to place, and never quite fits among other storks. The idea reflects our reality: we must become something else, move, constantly refashion ourselves to survive.Because of its unique form, the film belongs to a docu-fable, a new narrative mode. “The term did not exist before. It arose organically through the process.

Documentary has always been the freest form, refusing strict rules and genres. That is why I love it. Each story has its own style and usually tells the author what it wants to be. Some require interviews, some archives, others pure observation and cinéma vérité, others still use narration, animation, and more. Today documentaries are in crisis because streaming platforms restrain creativity and impose tight templates. No one should police what is or is not a documentary, as long as it shows real life on a socially relevant theme.”

I tell her I believe art must be socially engaged, although many still shy away from that stance. “Absolutely. I consider myself a socially engaged author and believe this is an artist’s responsibility. I do not believe in art for art’s sake. Art is expression and a powerful energy that shapes and changes lives and perceptions.

Anyone with artistic talent must be careful and aware of how they use that gift.

Otherwise art loses its value,” she says. The ending nearly mirrors the folk tale. “My biggest ethical dilemma was whether the film should end happily or sadly. Early on I was sure it would end with a tragic scene of people and storks living together in a landfill, an image of our consumerist reality. Circumstances led to a story of a man who saves a stork and a stork that saves an almost lost soul. At that point I decided the story needed hope at the end, to inspire everyday heroes not to abandon their values, no matter how hard things get.”