I often think about how my greatest fear isn’t death as disappearance, but death as forgetting. It seems that what we truly fear is not the end of existence, but the moment when no one speaks our name anymore. Forgetting is, in a way, a quieter and more lasting kind of death. While the body disappears once, memory fades gradually, over years, generations, with those who once knew us. Some people live forever through what they’ve left behind: through art, science, words, or stories that continue to echo. But there are also those whom oblivion swallows even while they’re still alive. Their names are no longer mentioned, their ideas fail to reach new people, and what they created remains locked away in dusty archives or in the memories of a few.

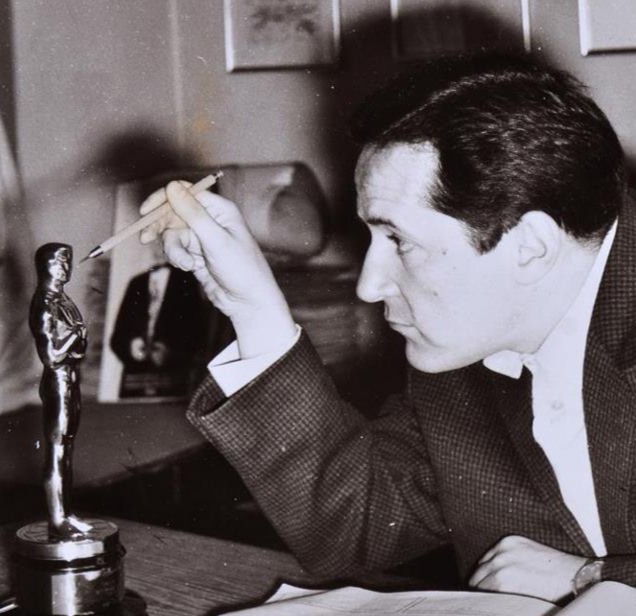

Such was the fate of artist and animator Dušan Vukotić Vud, one of the pioneers of Yugoslav animation, a man whose imagination expanded the boundaries of what drawing could express, and the only Oscar winner from the former Yugoslavia, for his 1961 short animated film Surogat. Today, his name is known to few, even though his work shaped an entire era of cinematic art. The film Vud, You Won, directed by Senad Šahmanović and screened last Friday at the Slobodna Zona Film Festival in Belgrade, brings back into focus the very questions of how we remember, whom we choose to remember, and how easily one can be forgotten. In my conversation with Šahmanović, we spoke about the importance of preserving cultural heritage, about play as the foundation of every creative process, about the child that endures in every artist, and about the difficult task of reviving—through a documentary—the figure of a man whose life was complex, almost mythical.

Senad Šahmanović reditelj. Photo: Svetlana Milović

When I told Senad how deeply moving and powerful I found both the title and the ending, he said that the closing line, “Vud, you won,” carries a universal message for him. “It’s a message about the importance of creation, about cultural heritage that remains for generations. It’s only a matter of time before it’s reactivated and reappreciated,” he explained. Sitting across from me in a noisy café, he continued in a calm yet firm tone, “I wanted us to leave a message for the generations to come—to show that society can change for the better, that we must value people who devote their lives to creation. Culture is a special kind of treasure because it’s something timeless, something eternal.”

I wanted to know more about his creative process and how he decided to make this particular story the focus of his film. He said that curiosity and challenge guided him in his decision to tell Vukotić’s story—how to portray a man who had already told so many stories himself. “Every author engaged in a creative process—be it writing, painting, or anything else—searches for themes that resonate, that they want to share with an audience, something that challenges them at that moment. For me, the challenge was how to tell a story that already exists, but to make it authentic, to offer a new perspective and a fresh interpretation of the material,” he said. “And I must admit, it wasn’t an easy decision. There’s always the risk of losing authenticity, of making a film that simply reproduces someone else’s work,” he added. “That’s why it was crucial to find a balance—between the authorship of the material I was using and my own creative vision.”

Slododna zona promo

While watching the film, I felt as if I knew Dušan Vukotić personally, mostly through the way he was portrayed as a friend, husband, and teacher. The people who spoke about him brought a special kind of warmth to the screen, revealing his character and creative spirit. In Senad’s words, as he answers my question about what it was like working with all of them, there’s a deep sense of respect, not only for Vukotić himself but also for his collaborators, family, and friends.

“Many of them, unfortunately, are no longer with us. Their testimonies might be the last ones ever recorded,” he says. “It was especially emotional in Zagreb when the families of some of our interviewees came and reminisced about the times when we were filming—and even earlier. For me as an author, sharing those experiences and conversations with them was invaluable. Then came the long hours in the editing room. And now, after the film is finished, all of it feels like a kind of treasure that’s hard to describe in words. It’s something that stays with you. I’ve grown through this process, both as a filmmaker and as a person—technically and spiritually. These are people who marked an era of a great cinematography, the Yugoslav one, and their achievements were truly remarkable worldwide. So this film has brought me so much—not just knowledge, but genuine joy that I had the chance to meet and speak with those people.”

Senad admits that what fascinated him most about Vukotić was his persistence and his faith in what he was creating. “This was the 1950s—there were no books, no tutorials, no examples to follow. He had to find solutions on his own. Out of that scarcity, a new style was born: reduced animation, a blend of lucidity, imagination, and modernism. Something entirely new came out of it,” he says. “As his friend Rajko recalls in the film, Vud carried a kind of Montenegrin sense of honor that people around him sometimes misinterpreted, what seemed like strictness was actually fairness. Maybe that firmness was just a mask, hiding the child within him. In the film, it’s mentioned how he used to play with toys. And one of his friends once said about his sense of honor and discipline: ‘If he hadn’t been that way, he wouldn’t have been anyone at all.’ I think that’s brilliant,” Senad adds with a smile.

As I listen to him, I can’t help but think how incredibly contemporary Vukotić’s films still feel today. His short formats, rhythm, and visual language are strikingly close to the pace and brevity of today’s social media era. “He was a visionary,” Senad says. “Within such a small space, through short form, he managed to say so much. That’s true mastery—to convey deep meaning in simple language.” The films The Game and The Grasshopper, which left the strongest impression on me while watching the documentary, perhaps best reflect that quality. “Those films were far ahead of their time,” he explains. “They combined live action, animation, and documentary elements—forms that only decades later became a trend.”

As our conversation unfolds, we naturally move toward the state of culture today. “That topic is always relevant in our region,” he says. “Governments change, systems shift, and yet artists remain on the sidelines. Everything that has been achieved gets relativized. And yet those are the things every society must protect. As Churchill once said:

“If we lose culture, what will we have left to defend?”

We also talk about the Slobodna Zona festival, which this year, for the first time in twenty years, was held without any state support, making it a truly unique and special edition. “That’s exactly why it was so important for it to happen,” Senad says. “The enthusiasm behind it is enormous. Continuity is crucial, it’s easy to pause, but it’s very hard to start again. This festival puts Belgrade on the map of European cities, and that’s priceless.”

At the end of our conversation, I ask him what he considers the greatest victory of this film. What does he hope the audience takes away after leaving the cinema? He doesn’t hesitate. “That we’ve pulled another great artist out of oblivion. After the screening, people stayed to talk, to ask questions, to reflect on his life and work. If even one person walked away wondering who Dušan Vukotić was and felt inspired to explore his films, that’s already a victory.”

I stop the audio recording and say goodbye to Senad. As I walk out through the crowd after the interview, I think about how small victories like this always restore my faith that culture in the Balkans still has a chance for a better tomorrow—because there are still creators like Senad Šahmanović, who, like a magician with a wand, manage to save people and stories from being forgotten.