Our Vučko: the story of the mascot of the Sarajevo Winter Olympics

Timotej JevšenakJanuary 27, 2026

January 27, 2026

The charming wolf Vučko, created by academic painter Jože Trobec from Kranj, remains the most popular character in the history of the Olympic Games. In 1981, an anonymous public competition for the official mascot of the Sarajevo Winter Olympics, which marked exactly forty years this February, received as many as 836 submissions, with records from the International Olympic Committee noting only a single wolf among them. After an expert jury selected six mascots, a public vote followed via newspaper coupons, in which Vučko convincingly won twice and became a global icon that also became a people’s symbol and is still very much alive. On the occasion of the Milan Cortina Winter Olympics 2026, we revisit this unforgettable event held in Sarajevo in 1984.

The story of Vučko for Vogue Adria was told to me by his “father,” Jože Trobec, who began his professional career immediately after graduating from the Academy of Fine Arts, during the golden age of the Kranj-based company Iskra, one of the leading and most successful companies in Yugoslavia at the time. Iskra prided itself not only on technologically high quality products, but also on sophisticated product design aligned with global trends.

“Iskra was light years ahead of other companies in Yugoslavia. It had its own design department led by Davorin Savnik. Right after finishing the academy, at his invitation, I joined Iskra’s graphic design department team. At the time I did not have much practical experience in that field, but over five years I learned a great deal within an excellent team. I also participated in the design and realization of the iconic Iskra telephone ETA 80.”

Drawing had been Jože’s greatest passion for as long as he could remember. Already in the first grade of primary school, he often helped his teacher illustrate classroom posters with letters and numbers.

“But when it came time to enroll in university, my family was not particularly enthusiastic about my choice to study painting. My mother would often say that engineers are neat and respectable, and artists are drunks.” (laughter)

He noticed the competition for the Sarajevo Winter Olympics mascot by chance in a daily newspaper. Since the task seemed interesting to him, he immediately accepted the challenge.

“Misha the Bear, the mascot of the Moscow Olympics in 1980, had achieved great popularity and clear commercial success, so I also wanted to create a character that would be friendly, pleasant, and at the same time commercially appealing.”

Before developing the idea for the mascot, he first summarized his basic starting points. These were associations tied to the context in which the Games would take place: Sarajevo, Jahorina, the green, forested, and diverse landscape of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In that context, the image of a wolf came to mind first.

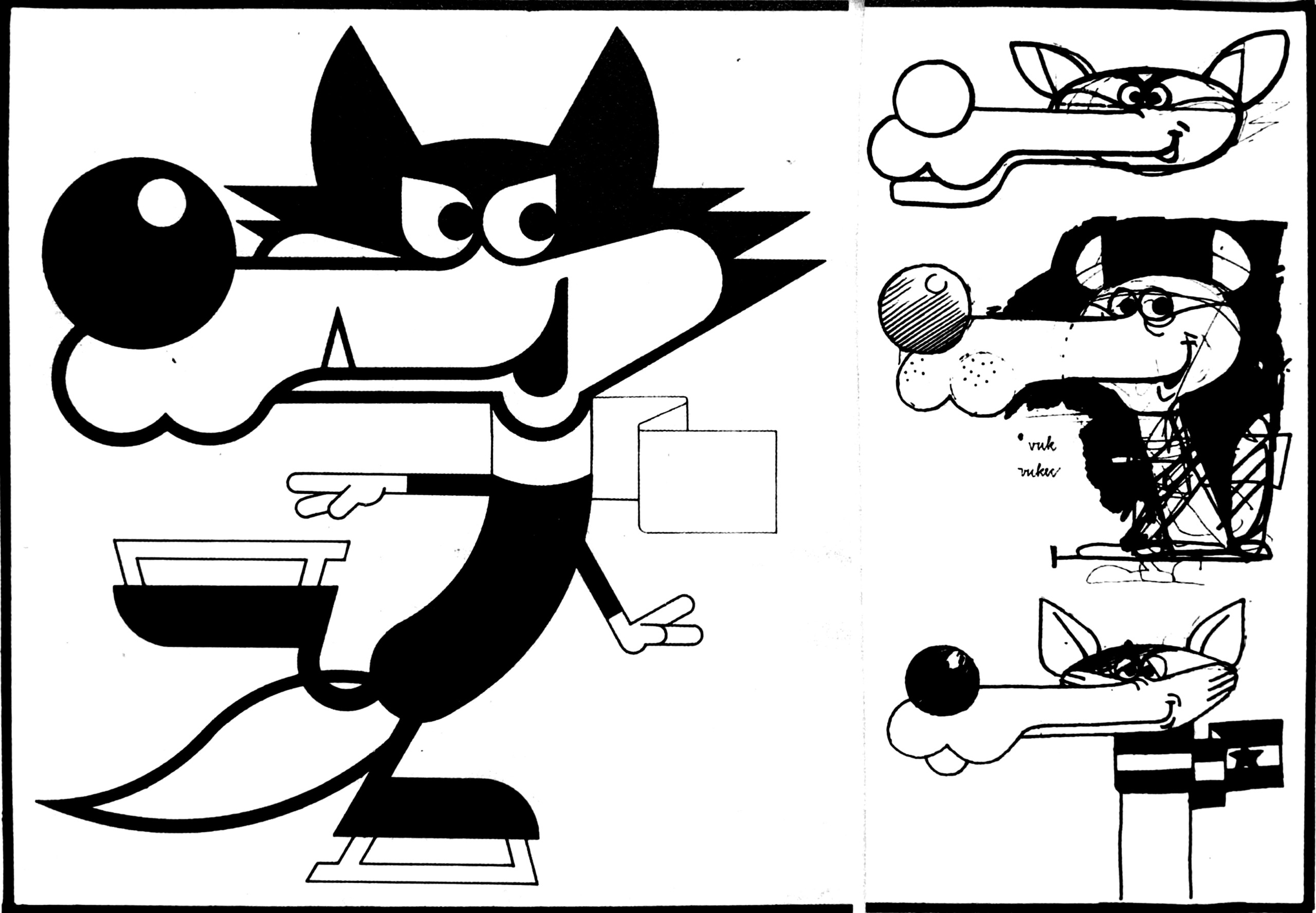

“At that moment, memories from my childhood surfaced, when I loved stories about Jahorina and wolves. Imagination began to do its work, but at the same time I consciously wanted to distance myself from a Disney-like appearance of the mascot. I made the first three trial sketches of the wolf and set them aside for a while.”

The public competition did not include specific limitations. Even children participated, cutting out their favorite comic book characters and sending them en masse as mascot proposals.

“The competition brief was not complicated. While developing Vučko, I also studied the pictograms of the Moscow Olympics, so it seemed logical to me that already at the competition stage I should prepare, in addition to the basic figure, three positions of the wolf in different sports disciplines: downhill skiing, ice skating, and ice hockey.”

His drawings lay on the drafting table for some time until his wife convinced him, just before the deadline, to pack them up and send them to Sarajevo, where his proposal arrived practically at the last moment.

“Mladen Kolobarić, the creative director of the Sarajevo 1984 Winter Olympics, later stated that even if my proposal had arrived slightly late, it would certainly have been accepted, because Vučko allegedly stood out strongly among the broad competition they had before them. He joked that they would even have been ready to ‘cheat’ to make my wolf win, because the expert jury’s opinion of him was unanimous.” (laughter)

Among the 836 submissions, the jury selected six mascots for the first final round: a hedgehog, a snowball, a mountain goat, a lamb, a weasel, and the wolf Jahorinko, as Jože initially named him.

“Voting was conducted through coupons in daily newspapers across the republics of the former Yugoslavia. Vučko won with more than half of all submitted votes, but due to a complaint by one of the competition participants, the author of the hedgehog mascot proposal, they were forced to repeat the competition.”

In the narrowed selection, the wolf once again appeared alongside the fox and snowball mascots. Jahorinko, or Vučko, thus convincingly won twice, both according to expert and public opinion, with competition that, in Jože’s view, was not particularly strong.

“Oskar Kogoj’s weasel was extremely elegant and beautifully shaped, but it lacked character. A mascot must have an important connecting function and carry a specific positive message. It must have personality and soul.”

The media reacted strongly when the wolf won. On one hand, there was much euphoric positive enthusiasm, while on the other, part of the public expressed indignation and concern that Yugoslavia would send a negative message to the world with such a mascot, as the wolf was believed to be a dangerous, aggressive, and bloodthirsty animal. In the first version, Jahorinko, or Vučko, had a tooth protruding from his lower jaw, but after the repeated victory in the competition, Jože did not have to make many changes or adjustments to his appearance in later stages of realization.

“A wolf does not attack without reason. It is an animal that fights for survival, and sport is also a struggle. Ante Sušić, then mayor of Sarajevo, told me at one of the meetings: ‘Joža, if you bring this wolf among the people, all respect to you.’ At that meeting we agreed to make him a bit friendlier by removing the tooth. That was the only visual adjustment, and the organizers changed the name Jahorinko to Vučko, little wolf, because the Games were not held only on Jahorina, but also at other locations.”

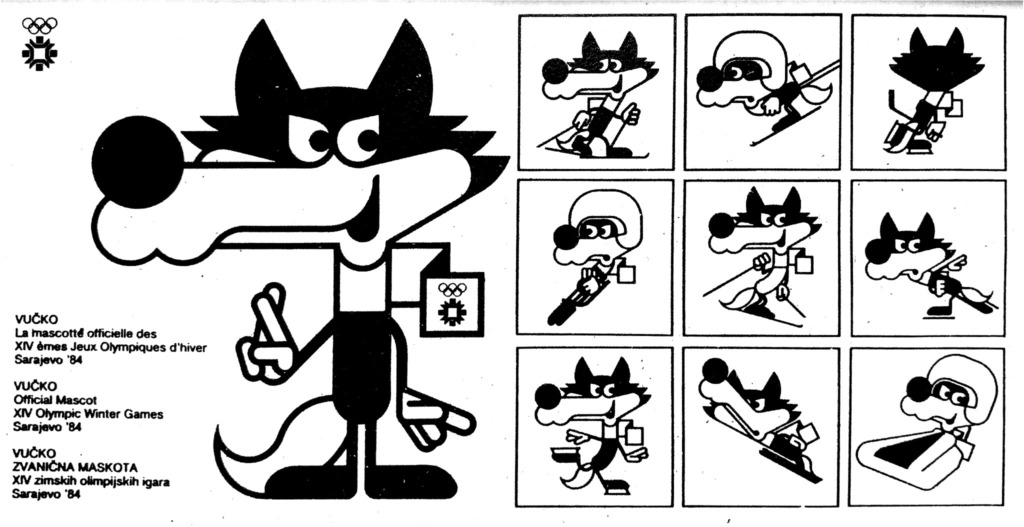

Vučko then also took on positions in which he did not participate in sports disciplines. He would simply greet people in a friendly manner with crossed fingers, or smile and laugh. Jože prepared these positions on his own initiative, even though he did not have much time to create all the pictograms and representations.

“The process lasted a good three months and there was quite a bit of pressure. There were nine pictograms in which he performs winter Olympic disciplines, as well as several so called atmospheric positions, where he crosses his fingers to wish luck to all participants of the Games. We also specially prepared his images for posters, for which I drew Vučko using colored pencils.”

The organization of the Sarajevo 1984 Winter Olympics was extremely complex and involved many domestic experts. Part of the creative team preparing visual materials included animator Nedeljko Dragić, puppeteer Ivica Bilek, graphic designers Branko Bačanović and Čedomir Kostović, and set designer Meta Hočevar. The voice for the opening song in the promotional spot was provided by Zdravko Čolić. However, Jože worked directly only with Bilek, because from the outset the organizers wanted Vučko to become three dimensional as well.

“Throughout Slovenia I searched for experts who could bring him to life in a way that the three dimensional representation would express his positive character. We tried with model makers at Iskra and puppeteers from the Ljubljana Puppet Theatre.”

Their efforts did not pay off, however, because they failed to capture Vučko’s true character, his soul, as Jože calls it.

“Until Kolobarić called me and recommended the puppeteer Ivica Bilek. We exchanged contacts, and I immediately sent several of my drawings to Sarajevo with that goal.”

On his next visit to Sarajevo, Bilek greeted him with the first plush Vučko already at the airport terminal.

“I cried with happiness, because he captured his character down to the finest detail. I remained friends with Ivica until his death.”

Vučko is a specific icon not only because of his exceptional recognizability, which he still has today as the most popular Olympic mascot, but also from a graphic perspective. His image is highly adaptable from small to large scales, among other reasons because it is composed of basic geometric shapes, which allowed even manual reproduction of Vučko using drafting tools based on a grid. However, with such mass application of the mascot, users often did not adhere to graphic guidelines. Jože also remembers many “altered” versions of Vučko.

“With such frequent use of a character like that, it is difficult to keep everything under control. For these reasons, I technically constructed Vučko from pure geometric elements, circles, straight lines, and curves. I was guided by practical experience at the company Gorenjski tisk, which mass produced packaging for large Yugoslav companies and their products.”

There he came into contact with the first computers that technicians used to create packaging. They entered points that connected into lines, which he found remarkable, so he also constructed Vučko according to that basic geometric system, but not using a computer.

“I drew everything by hand myself. With a compass, a technical pen, and other drafting tools.”

Many different products were produced in the form of or featuring Vučko, which can still be found in many homes today. Thermometers, radios, keychains, badges, glasses, mugs. During the Olympics alone, as many as 126,000 plush Vučkos were sold, thanks to which a Croatian factory even built a new production hall. However, despite repeated calls to sign contracts, there were complications regarding Jože’s author rights, even on the part of the financial director of the Games’ organizing committee.

“The copyright agency filed lawsuits three times in a row immediately after the Olympics, but without success. Then Kolobarić called. He proposed that we settle for 16 million dinars. At the time, that was the price of a new Zastava 101 or a garage. We consulted and eventually settled, because a lawsuit would have dragged on endlessly. I went to Sarajevo on a Friday, had dinner with Kolobarić in the Baščaršija, and on Monday the money was in the account. And I immediately bought…”

An apartment?

“No, a garage.” (laughter)

Jože describes his personal memories of the atmosphere in Sarajevo during the Olympics as very positive and pleasant, although as the author of the mascot they initially “forgot” to send him an official invitation to the event.

“A few days before the opening, I had an interview for the newspaper Oslobođenje, in which the journalist asked me what I would be watching at the Olympics and in Sarajevo. I honestly replied that I did not know, because I had not yet received an official invitation. The article caused a strong reaction early the next morning. My wife and I immediately received a telegram with an invitation, the highest possible accreditation granting free access to all events and VIP boxes, accommodation at the Holiday Inn hotel, and a stewardess who met us at the airport and drove us around Sarajevo wherever we wished throughout the days.”

Vučko is a phenomenon, having become a universally accepted character that is internationally recognizable. He did not fade into oblivion like many mascots created for various events that are momentary and quickly become part of the past. Yet even today, Jože has no answer to the question of why he has remained so popular and timeless.

“People simply accepted him as their own. According to official data from the International Olympic Committee, Vučko is still the most popular mascot of all time at this most important sporting event. And you know what they say in Bosnia? ‘The one thing we all agree on, that is Vučko.’”