A well-known TV personality, director, activist, and much more, Maša Memedović recently returned from Namibia, impressed by the horizons she experienced there, especially one region where she spent the most time and from which come these cinematic scenes she shared for Vogue Adria.

For Maša Memedović, mountains and nature have always been alluring, and Africa led the way in that seductiveness, as a place where she could experience something completely different. Of everything African, Namibia seemed to her like a place where wilderness can be felt in a different way. “Namibia has always associated me with emptiness. The general facts were familiar to me; that it is the most sparsely populated country on the planet, that the Kalahari and Namib deserts are there, and that it has plenty of wildlife. In my mind there was a dirty yellow color palette. And the trip to that country came about unplanned.” And that was last December, which, as Maša tells me, is actually the ideal time to visit this African country. “The weather is pleasant, not extremely hot, which is good for camping. December allowed us to fully enjoy the landscapes and made all activities comfortable.”

Traveling by jeeps was their chosen mode of transport, and beyond the sense of adventure, it served above all a practical purpose due to the specific conditions that prevail in Namibia. “It is a vast country with a disproportionately small population. Cities are spread out, and the distances between them are therefore large. The roads connecting cities are good, but to be closer to the animals it was necessary to go off-road, and that requires appropriate vehicles. That is what truly set our trip apart from classic tourist tours. Traveling by jeep allowed us to experience the country fully and to be in constant contact with nature. I always prefer traveling by car because it gives me freedom. You can stop wherever you want, explore at your own pace, and experience places that are inaccessible to standard tourist routes. That way we had the opportunity to observe animals where they actually belong, in nature,” says Maša, adding that they organized the trip with the help of a Belgrade-based agency, especially highlighting small, intimate groups as an advantage and “the feeling that you are going on an adventure with friends you have known for years.”

Before I surrendered myself to Maša’s written notes from Namibia, I was also curious why she chose those particular parts of the country, which impressed her endlessly, as you will see below. “The agency we traveled with has a local guide who lives in harmony with nature and constantly explores Namibia: camping, driving, getting to know the country firsthand. Thanks to him, we visited places known only to locals, places we would never have reached on our own or where standard tourist tours do not go. That gave us an authentic experience and an adventure that is truly special.”

Read on to find out what impressed Maša about Namibia, a country that is definitely quite different to visit compared to classic tourist destinations.

Beginning

We landed in Windhoek in the morning. The city was quiet and orderly, with low houses and wide streets, as if it still had not decided whether it belonged to Africa or to some other continent. At the airport, our hosts welcomed us, brief greetings, distribution of equipment, jeeps lined up in a row. There was no ceremony. Just departure. The plan was as follows: we head south, toward the Namib and the Kalahari, then west to the coast, Swakopmund, Skeleton Coast, then north along the ocean, and east toward Etosha, before finally returning south.

We traveled in a convoy of six jeeps, four people in each, twenty of us, with four guides: Đorđe and Ivan, and the locals Chris and Jack. The tents were on the jeeps, water canisters in the trailers, dual fuel tanks, and a refrigerator with food. We drove 4×4 vehicles, Ford Ranger and Toyota Hilux. Over fourteen days we covered about three and a half thousand kilometers, punctured five tires, burned out one set of brakes, and had several minor breakdowns.

Namib

In the first days, the road led us toward the Namib Desert. As we moved away from the city, the landscape broke into layers: savanna, rock, then sand, mountains, plains, dunes. Horizons changed without warning. The drives were long, the conversations short. The landscapes spoke for us.

The Big Daddy dune appeared suddenly, immense, without any proportion to a human being. The ascent lasted longer than it seems from below. The sand slid underfoot; every step forward was half a step back. From the top, the world seemed flat and distant, as if everything were happening without you, and when you turn back, you sink into endless curves of dunes stretching into infinity. At the foot of the Big Daddy dune lies Deadvlei. Even greater than the view itself was the descent down the dune, where with every jump you slide another half meter down the warm sand.

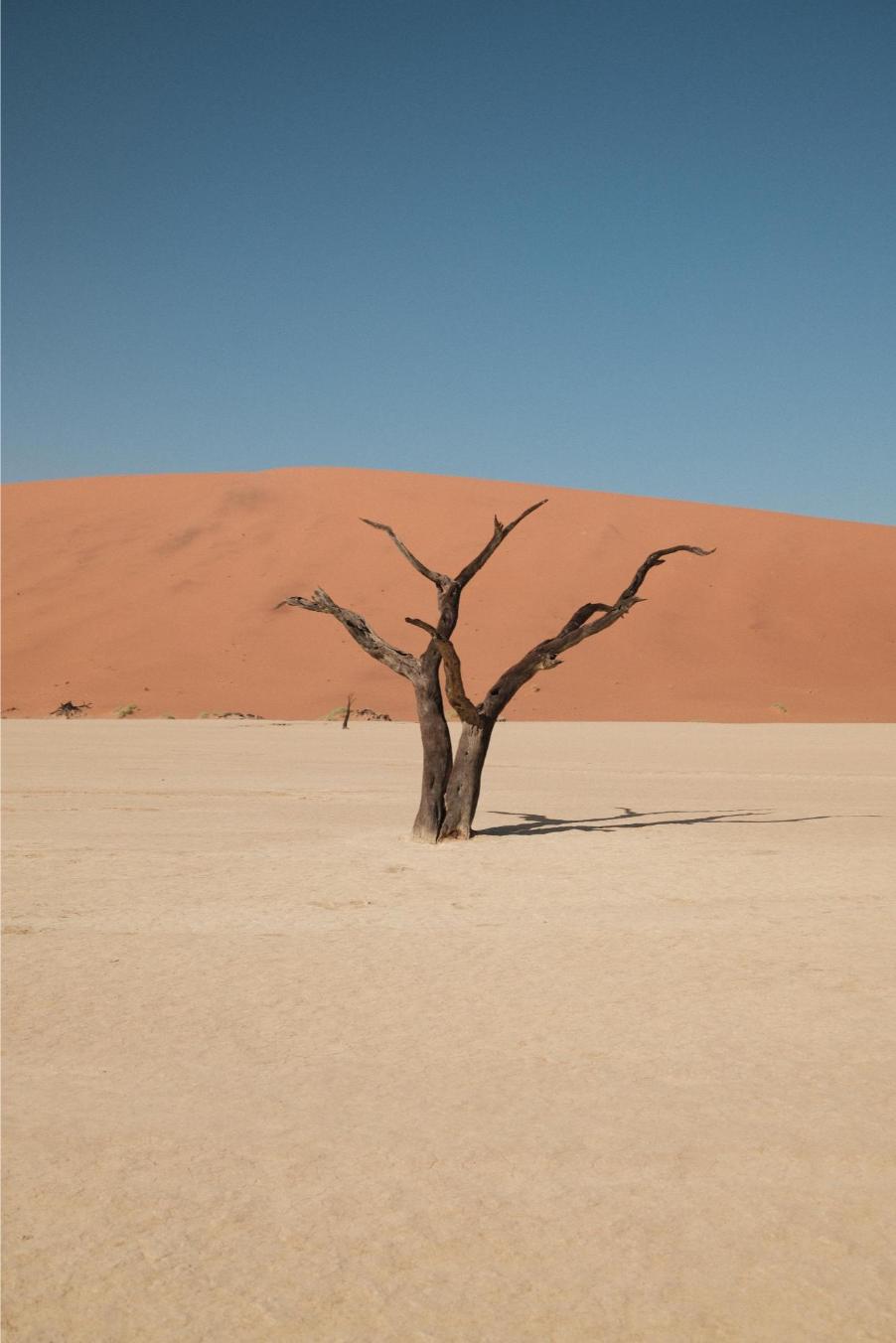

Deadvlei is a valley in the heart of the Namib Desert, a place where water once flowed, and now only grooves of dried clay remain. In Deadvlei there is complete silence. Black trees, dead for hundreds of years, stand motionless on white clay, surrounded by red dunes and a blue sky. It does not feel like a place of death, but rather a place that remembers that life once existed here.

As we continued on, it became clear that the country’s name is misleading. Namib means “a place where there is nothing,” but in that emptiness everything was present: time, space, movement, life that has adapted and survived without excess.

Plants here do not wait for rain. They obtain water from winds that come from the Atlantic Ocean in the form of fog. Leaves are replaced by thorns, trees reduced to a minimum, and roots either deep or widely spread in order to retain the little moisture that arrives.

Animals have learned not to waste energy. They are active at night or in the early morning hours, while the cold still holds. The color of their fur follows the color of the ground, movement is economical, tracks are short. Oryx and springbok can go days without water, elephants cross vast distances in silence, following memories of water sources that often no longer exist. Everything is subordinated to survival, without haste, without excess, without error.

Still, sometimes it cannot do without human help. During long droughts, water disappears faster than memory, so people have created waterholes. Not to change nature, but to give it time. Discreet places, without signs or noise, where water lingers. Animals come as they do everywhere else, cautiously, according to an established order.

Camping in the desert

We left the desert slowly, almost imperceptibly. Sand turned into rock, rock into low grass. The road became firmer, faster, but the sense of vastness did not disappear. In Namibia, distances are not measured in kilometers, but in time spent in vehicles.

Days in the camps had their own rhythm. Waking before sunrise, a quick coffee, packing the tents. Driving. Breaks without a particular reason, simply because the landscape demands a stop. Nights were cold, with a sky that does not remember light pollution. The stars were not just a backdrop, but a space in themselves.

When evening fell, we were already settled in camp, tents pitched and a fire lit. There was no need to turn on lights, the moonlight was full, colors were discernible in the dark, and shadows were sharp as during the day. We turned on our headlamps only when jackals crept close to the camp, to drive them away with beams of light.

After a couple of beers and dinner, prepared for us by our hosts by the fire, we tiredly gathered the impressions of the day and planned the next one. Most people could not remember what happened yesterday, because today lasted a long time. Landscape after landscape, one impression after another. Sensory stimuli lining up at every new bend. One easily falls asleep inspired by such experiences, deeply, so much so that only in the morning, by the tracks around the tents and vehicles, can one see that during the night a herd of elephants passed right beside them.

All shades of yellow

As we approached the north, the colors changed. Red gave way to ochre and gray, and the horizons expanded even more. One of the words that could often be heard on the journey, both among us travelers and among the guides, was ETOSHA. For me, it is a beautiful word with no particular meaning. As I said at the beginning, my knowledge of Namibia was reduced to a dark yellow color palette. Very quickly, that word acquired a special place and special meaning in my mind.

Etosha

A national park the size of Belgium, named Etosha, is a plain. Vast, white, almost blinding from the light. A former lake, now a dry salt pan that reflects the sun so strongly that the boundary between sky and earth is erased. In that plain, everything is exposed. There is no shelter, no hiding. However, along the edges of the salt pan there are areas where grass and low trees follow waterholes and rare sinkholes that still retain moisture. There animals find shelter and food. Oryx graze on low grass, giraffes tear leaves from dense acacias, and antelopes seek shaded parts of the plain.

Waterholes are centers of life. Everything intertwines there: water, food, shelter, and the rhythm of nature. Here too, most waterholes are man-made, to help the animal world return to balance. Etosha is balance. Water brings life, grass and trees sustain it, and animals preserve it.

Elephants arrive first, heavy and confident, as if the space belongs to them by some ancient right. Rhinos approach more cautiously, always on the edge. Zebras, antelopes, giraffes, constantly moving, constantly alert. Predators wait. They are not always seen, but they are felt.

During the day we would drive through the park in search of animals, from waterhole to waterhole, following whatever we encountered along the way. We split the convoy into groups of two vehicles, thus expanding the field of vision. We stayed in contact with the other vehicles via radio, and everyone was expected to report immediately as soon as they noticed something.

As soon as we entered the park, we saw a black rhinoceros, an animal we had been trying to find for the previous ten days. That is Etosha, everyone is there. Shortly afterward, trophies followed one after another, animals familiar to me; the only one we did not see was the leopard.

The park closes for movement in the evening. We stayed in camps by the waterholes. Night in Etosha carries a different weight. Sounds come before images. Footsteps, breaking branches, the deep breathing of something large that you cannot see.

This was a journey during which we had no contact with people, except during brief stops in civilization where we procured supplies for the continuation of the trip. Namibia is not emptiness. It is a space where every step, every breath, and every glance carry weight. A land that at first glance seems harsh and desolate is actually full of life that has adapted, that asks for time and space, and that teaches us patience.

What you should know before traveling to Namibia

Best time to travel?

From May to September, during the dry season in the country, known for moderate daytime temperatures and clear, sunny weather, which makes it an ideal period for long days spent on an African safari. The transitional months of April, October, and November are also an excellent option due to pleasant weather conditions, with the added benefit of fewer visitors outside the peak season.

How long is the flight?

From Croatia, Slovenia, Serbia, and the region, the flight takes around 12 to 16 hours in total, with one to two layovers. The most common routes go via Frankfurt, Doha, or Istanbul, arriving in the capital, Windhoek.

The best way to get around Namibia?

Renting a 4×4 vehicle is almost mandatory, and the roads are long and deserted, so it is important to plan the route and fuel carefully.

Traveling with an agency or independently?

For a first visit to Namibia, an organized trip with an agency definitely offers the most advantages: transportation, accommodation, safari.

Official language in Namibia?

English.

Types of accommodation in Namibia?

Hotels: In the capital Windhoek there are many hotels, from simple to more luxurious. Similar options exist in Swakopmund on the coast, Walvis Bay, and other larger towns. Hotels are a good option before and after long journeys.

Lodges and guesthouses (local homes or small hotels): Lodges are a common option in tourist areas such as Etosha National Park or Sossusvlei. They usually offer comfortable rooms, breakfast, and often meals, and may include guided excursions and safaris. Guesthouses or pensions are often a more affordable and comfortable middle option.

Camps and camping: Camping is very popular and often the most affordable option, with camps located in national parks, for example in Etosha, and along main routes. Within safaris there are options for tents with comfortable beds and safari lodges that provide a sense of authentic stay in the wilderness. They come in very luxurious versions, with views of the desert and the starry sky above you.

Photo: Maša Memedović, Bogosav Apostolović