Faces have always fascinated me. Even the smallest twitch at the corner of a mouth or a raised eyebrow would capture my attention, prompting me to try to read someone’s thoughts, their life, what goes through their mind as they sit on public transport, wait in line at the bank, or gaze into the distance on a beach. I believe a photograph becomes exceptional the moment it captures those raw, honest fragments of everyday life. Much like in film, what has always drawn me to photography is the act of documenting something unfiltered—situations and scenes that we all recognize or have been part of ourselves.

The first time I saw the work of British photographer Martin Parr, I thought I was looking at grotesque oil paintings, bodies caught in a trance. But then I began to notice the details: gestures, the glimmer in the eyes, cracked skin, thinning hair, chipped nail polish, faded tattoos, discarded trash, toys buried in sand after a day of children’s play, drowsy people unconcerned with the lens of a skilled photographer who elevates ordinary moments into high art. Moments like that scene of family chaos where a mother tries to wipe ice cream off her children’s faces amid the crowd of an overcrowded tourist beach become symbols of reality, forever frozen in that mix of disorder and consumerism. The seagulls rushing to grab the leftover fries on the shore make us think that Martin is simply always there, in the right place at the right time.

Martin Parr, England. Clacton. 2017.

To make things even more complex, and my relationship with Parr even more complicated, I wrote my master’s thesis on his work. His photographs gave me exactly what I needed at that moment—something raw, something true, something that made me feel as if I had traveled the world, something that pulled me out of the dull routine of student life. They still have the same effect on me today. Simply put, they show both the good and the bad sides of modern life, with Parr always managing to capture the extremes. These everyday scenes are just as important to document as anything else. Life on the beach, dog shows, melting ice cream, family chaos—they make up our lives, and we should make sure that future generations don’t see only war photography, social issues, or Instagram selfies in the archives.

We also see ordinary life—sometimes funny, sometimes surreal—but always through an unfiltered lens that Parr provides, along with his distinct perception of reality.

Unlike the old masters and their photographs often described as timeless, Parr’s images are anything but. On the contrary, they are deeply tied to the moment. They are rooted in their era, and that is not a flaw.

I spoke with Martin on a hot July afternoon, just after his trip along the Croatian coast, which wasn’t purely for leisure. At moments, he hinted that we might one day see a project emerging from that journey, which delighted me. When I asked whether it had been difficult for him, this time, to turn the camera on himself, at least metaphorically, for his autobiographical project, he gave me a typically British, straightforward answer: “I knew I would be the only person who’s always there,” he explained. “When we started those studies, it became clear that it had to be me. I couldn’t smile, because that makes the pictures boring.” His new autobiography, brilliantly and wittily titled Utterly Lazy and Inattentive, reveals how his artistic practice has matured over the years. “This book helped me see how everything connects. You can trace the development of my work in it, how my interests have sharpened. From photographing tourists to beach scenes, those themes have always been constant,” he explained.

Martin Parr, RUSSIA. Mosow. McDonalds. 1992.

Although he didn’t discover anything particularly surprising about himself or his creative process while working on this project, looking back at his work was important to him because it allowed him to connect all the pieces and see the line of his artistic path. “By the age of fourteen, I had already decided I would become a photographer. That’s what I’ll do for the rest of my life, until I drop dead. I knew it when I was very young. It was a firm decision. Don’t ask me why, I just knew it was the right thing,” he said. The title of the autobiography comes from an unusual but humorous anecdote from his school days, Martin explained with a half-smile, when he was about twelve or thirteen.

My French teacher wrote that on one of my assignments. My mother tore it up, and I pieced it back together. It stayed in my memory ever since.

When we were choosing the title for my autobiography, I suggested it, and everyone loved it.” This project is also the first in which he collaborated with writer Wendy Jones, who recorded his photographic stories and shaped them into a coherent narrative. “She had a tape recorder, I talked about the photographs, she transcribed and edited everything, combining it into a whole that follows my life chronologically.” Immediately, images of his most famous photographs began to play in my mind—the ones I’m sure we’ve all seen at least once, perhaps without realizing that Martin Parr was the author behind them. What defines all his works are the vivid colors and use of flash, which have become a kind of signature of Parr’s visual identity. With that in mind, I asked how his visual language helps him explore himself, and whether photography also serves as a form of self-discovery. He answered simply but effectively: “I create photographs that reflect my view of the world. I’ve always loved bright colors and flash. I took that from commercial photography, realized I liked it and that it represented how I see the world, so I applied it to my own work.” That honesty shows how photography for him is both a personal expression and a way to clearly convey what he sees and feels, always perfectly aligned with the times—and for contemporary art, that is certainly one of the greatest strengths, as well as challenges.

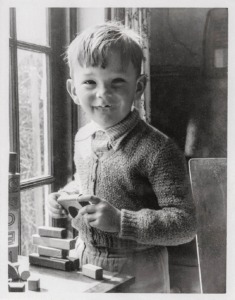

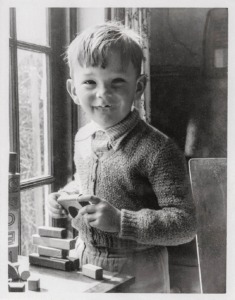

England. Martin Parr. Age 5. 1957.

I was also curious how he sees the difference between a selfie and a self-portrait, given today’s obsession with selfies on social media. Does he think that difference even exists? With a slight smile and a short pause to consider the question, he began: “Yes and no. I communicate through photography, and I rarely talk about it. I try to make my images entertaining and engaging, and if people want, they can look for politics or meaning in them—but I don’t impose it.”

His early works, such as The Last Resort and Small World, carried a strong social commentary. “What I’m doing now is just a continuation and expansion of all that,” Martin said. “I’ll never stop exploring those themes. I’ve just returned from Croatia, where I was photographing on a cruise. Places like Split are full of tourists, which is perfect for my style,” he added with a laugh. I had to ask him about the absurdity itself and about the balance between empathy and documenting that absurdity, since I see it as one of the most important strengths of his photography. “I don’t control anything. I just take pictures. Other people, researchers, journalists, art historians—are the ones who draw conclusions,” he said, laughing. “My job is to make photographs that interest me at that moment, and if someone wants to, they can later read into them whatever they like.”

Despite the digital age and the new aesthetics of social media, Martin believes his approach is more relevant than ever. “More people are traveling now, especially after Covid. Places like Rome and Venice are overcrowded, and that gives my photography meaning.” In the end, his relationship with his native Britain remains complicated. “It’s a love-hate relationship. We all love the country we come from, but politics frustrate me, especially the rise of the right wing. Still, I love the simple things—Britons have a good sense of humor, good television, good radio.” Martin is also planning a new book about Britain and says he will definitely publish it within the next five years, though that’s all he can reveal for now. “Everything’s already there, we’ll easily pull something together.” When asked about future projects, he said that this summer he plans to photograph northern England, a theme he hasn’t explored much before.

And while talking about the Balkans, he doesn’t hide his appreciation for the food and coffee, though his ambivalent relationship with the crowds, which, as he says, “may not be pleasant, but they’re good for my camera”, still brings him a certain kind of satisfaction.

Anyone who knows even a little about the work of this great British photographer understands that he doesn’t simply record people and places—he captures the way we live, with all the imperfections and paradoxes that surround us. His work is neither a cliché about beauty nor a critique of reality; it becomes an honest reflection of what life looks like now, in its seemingly chaotic form. In a world that is increasingly filtered and constructed, Parr reminds us that art can exist precisely in that immediate, imperfect, and often unglamorous essence. His ability to document such moments with empathy and sharp insight makes his work enduring, because it offers neither victories nor defeats, but an honest image of ourselves.