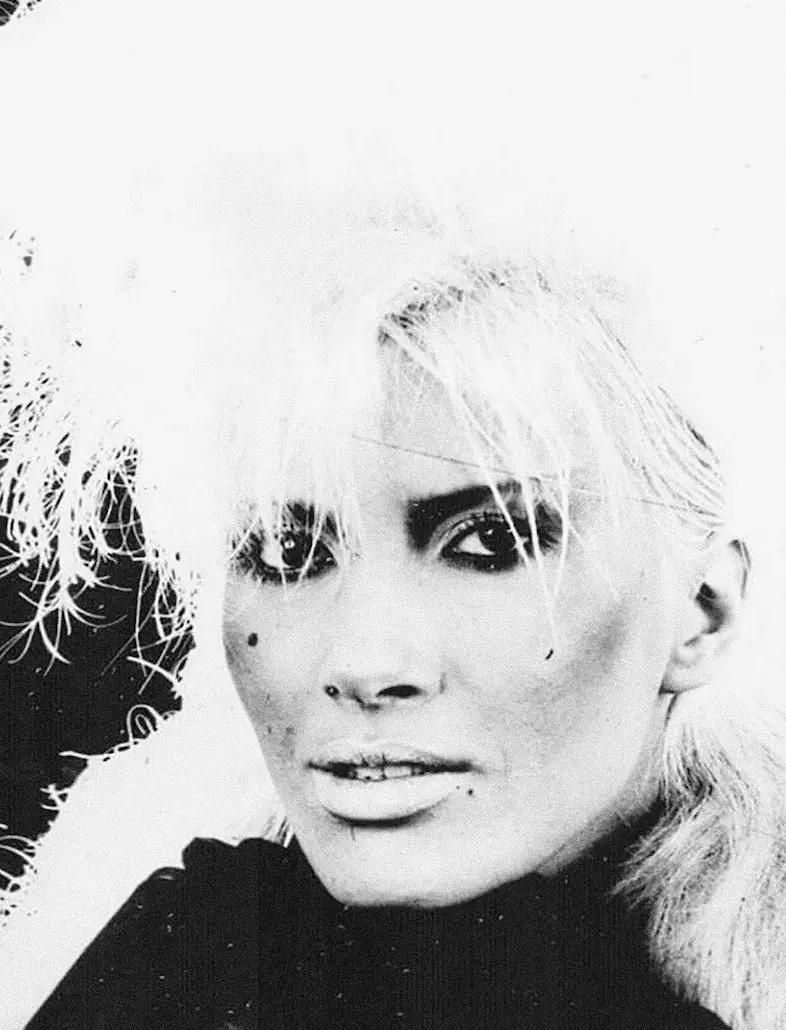

I met Brena three times. The first time I was six years old. At that time, there was already a big craze for Brena among us children, so I competed with my friend from the neighborhood to see who would be the first to get the album “Bato, bato”. The phenomenon that Brena represented when she appeared is difficult to explain and perhaps impossible to understand for those who did not live at the time. Boys, girls, dads and moms (OK, maybe moms a little less) all jumped on the bandwagon called Lepa Brena, which seemed to be leading to places out of this world. Her hot pants were part of the sexual revolution in our country, and children (both boys and girls) bought Barbie dolls with her image in hundreds of thousands of copies. Maybe you’ve seen footage showing the mania surrounding the Beatles, Elvis or later Michael Jackson and Madonna? I am not exaggerating when I say that it was like that when Brena appeared. (Those who possessed a folk cap with fringes, from Lika region of ex-Yugoslavia, were lucky because they could imitate Brena’s image from the “Tight Skin” movie).

The second time I met her was at a photoshoot in 2011. A friend told me he was working on a photoshoot with Brena, so I immediately asked him to bring me along. It was important for me to meet in person the woman who had influenced me so much in my childhood. She was extremely professional, which surprised me given how many stars and models behave on set. Brena was down-to-earth. This both surprised and inspired me to try to make some changes in the fashion industry in which I was working. I always told my colleagues: “No one should treat you poorly. If it happens – stop the shoot.”

The third time I met her was in October this year. I wanted to interview her and complete this journey from my childhood by giving her the recognition she deserves. There were many stars on our scene before and after her, but there has never been a phenomenon like her. After four days of shooting in four cities and two countries, we arranged a meeting for the interview. When we set up the initial meeting to organize the shoot for the November issue of Vogue Adria, she invited us to her office. When we were setting up the interview after the shoot, she invited us to her home. As I entered her house, I realized we had established a relationship of trust and that what we had created meant something to her. We brought two bottles of white wine, even though we knew she usually doesn’t drink, but with just a few hours left until her birthday, I had a feeling this might be a special moment.

“Are you from Vojvodina?”

“I am. Novi Sad. You must hear it in my accent.”

“I do,” she says with a smile. “That’s why I asked.”

Her tone changes at that moment, as if we’ve suddenly grown a bit closer, and she turns to her friend.

“Pour some wine for me, please. So I can tell everything I shouldn’t.”

They head to the kitchen and stay there, clearly feeling they’re no longer needed.

“Novi Sad saved me.” She takes a sip and continues. “You know, when we’d finish a performance or a concert, everyone from my band would go home to someone. I had no one; I was completely alone. That city was my oasis of peace. After two concerts a day, I needed simplicity, a reset. I needed a break from Lepa Brena. And I found it in Novi Sad.”

“No fans interrupting you on the streets?”

“Of course, there were. But in Novi Sad, when I’d walk by, they’d say, ‘There’s Lepa Brena’” (she mimics the Novi Sad accent and laughs). “And that’s exactly what I needed.”

“I’m glad we helped.”

We must remember that she was never merely a “singer,” a term that can sound derogatory even today—meant to imply someone just there to sing and entertain, from whom people rarely expect opinions, values, or success.

“None of us are really aware when we start what’s going to happen. But every being on this planet has a path and a purpose. I’ve met so many successful people in my life, both here and abroad, and I think that those who achieve great things are fundamentally very simple.”

“Was there a specific moment when you thought, ‘That’s it, I made it’?”

“Yes, when I first appeared on Minimaks’s show, I knew that was the start of my career. The second moment was when I performed at the Dom Sindikata hall, my first of thirty-one consecutive concerts. Walking across that stage, feeling the audience’s reactions and love, I realized this was it.”

“Is that when Lepa Brena was born?”

“My high school basketball coach gave me the nickname Brena: ‘I can’t call you Fahreta; it’s too long. I’ll call you Brena.’ At that moment, I thought: fine, he can call me whatever he wants, just for basketball. But the nickname stuck. And then Minimaks, before that famous show, added the ‘Lepa’ (Beautiful). When he announced Lepa Brena, I thought he was introducing another guest. I didn’t realize he was talking about me.”

Nowadays, we don’t see phenomena like those we had in the ‘80s. Brena released her first album in 1981, and within just three years, she became such a big star that she was invited (something many people don’t know) to sing at the opening of the Olympic Games in Sarajevo in 1984. “It was an incredible honor for me. I sang with Balašević at the opening. He was a special person. A poet. Someone who, like me, didn’t change despite all the fame.”

Brena was not like her peers. With her parents’ blessing, she started singing at dance parties at the local theater in Brčko as early as high school, earning money. She admits it was twice as hard because she had to balance work with school, sometimes after only a few hours of sleep. “Then I’d come to the first class, and the teacher, who had been at my show the night before, wouldn’t even put down the attendance book before calling, ‘Jahić, come out to the board!’ I always had to go first! So, I had to study harder than everyone else to make sure I was never caught unprepared.”

That was also when she dyed her hair blonde, marking the beginning of the Brena we know today. “My mother sewed all my costumes. She was a tailoring genius. And I always knew what I wanted and what made me feel good. I think that freedom, of a young woman feeling comfortable in her skin, was something the audience later recognized and accepted. But still, I never wanted to cross the line. I wanted everyone watching and listening to me to feel good.”

Today’s readers and audiences might not realize just how controversial Brena was when she appeared on the scene. She wasn’t just another singer; she was the first of her kind, a unique figure, and the resistance and criticism she faced were not easy to handle.

“From an early age, I had to deal with prejudice. I’ve never shared this before—when I was in high school, they held elections for the president of the Communist Youth League. I thought, ‘Why not?’ and applied. They told me I couldn’t be elected because I was a ‘singer.’ I couldn’t understand why I was penalized just for working and earning my way while others lived off their parents. I still don’t understand why singers aren’t given the same credibility as other professions. So, as you can imagine, I had to work even harder to prove myself and show them I was good enough.”

After high school, she went to Belgrade to study.

“I had to study and pay for my tuition and apartment. I wanted to know what my future held. I asked my dean what I would become after finishing my studies, where I could work, and how much I’d earn. When he answered, I realized that wasn’t the future I wanted. I remember my parents had bought me new boots and a large brown cape before I went to college. After that conversation, I decided to go back and tell them I wanted to sing and get their blessing. I wanted to earn my own way.”

She coughs slightly, takes a sip, and sighs. You know the feeling when someone is about to reveal a vulnerability? Lepa Brena, sitting across from me on her white loveseat, puts her wine glass down on the side table, twirls a strand of hair again, gently adjusts her vest as if she’s warming up, and says:

“At that time, bus stops didn’t have shelters, and suddenly this terrible rain and wind started. The umbrella I had flipped inside out, and the fabric of my cape soaked up more and more rain, becoming heavier and heavier. Then, two lightning bolts merged, making a thunderous sound as if they struck a power line. A stray dog approached me and stood beside my feet to shelter from the rain. That’s when I thought: ‘I’ll never wait in the rain again. I’m changing my life.’” And she adds, sincerely, what was the first thing she did after transforming from that soaked girl at the bus stop into Lepa Brena.

“I bought a raincoat. Waterproof and warm.” As she says this, she runs her hand over her vest, and I imagine a scene from Gone with the Wind playing out, not in the American South, but in Belgrade.

“If you could go back and talk to that soaked girl at the bus stop, would you have any advice for her?”

“I would tell her that life is fantastic. But it all had a price.”

“Now that you know everything you’ve been through, accomplished, sacrificed, would you choose the same path?”

Without hesitation, she answers, “I would never choose the same path again.”

“No?”

“No. Maybe I would be a doctor. That’s what I wanted when I was little. But I know that if I could choose, I’d choose to be a man. Because I’ve gone through it all and know how hard it is for a woman. And if you’re a beautiful and smart woman, the danger is that everyone wants to manipulate you and claim you. It took a lot of strength and wisdom to remain my own person. Maybe that’s my greatest success—that I stayed true to myself.”

For that authenticity, honesty, and freedom, she was both adored and criticized.

What was the strangest gift you ever received in your career?” I ask, genuinely curious.

“When I went to sing in Romania, it was an incredible experience. Back then, the Ceaușescu family ruled Romania. They took me to the stadium in Timișoara, where the crowd threw flowers at us when they saw us. I cried so much. During the concert, they lifted me on a crane above the audience, and up there, I sang ‘Long Live Yugoslavia’ while I saw tanks with raised turrets surrounding the stadium. I thought they were relics from 1945, that there was no way they were there for me. And then I realized how they lived compared to us, even though we were a socialist country. I was ‘the West’ to them, even coming from Yugoslavia. I was a potential spark against the regime. After the concert, they took me to a presidential suite. It was so big I needed a lot of time to get from the bathroom to the bedroom. Then security took me to a refrigerator to show me a special gift delivered just for me. When they opened the fridge, there was a bottle of Coca-Cola.”

“What was it like in Bulgaria? How was it performing in front of tens of thousands? Brena, that helicopter landing!”

“Well, you know all about that, but did I tell you that I visited Baba Vanga, the clairvoyant when I went to Bulgaria?”

“No! Did she predict anything?”

“She predicted everything!”

Some parts of this conversation I need to keep to myself, but I feel she recognized a kindred spirit, one prone to astrology and fortune tellers. “The things she told you must have sounded completely crazy?”

“Absolutely. But she only said nice things. She told me I’d marry a man in a white uniform, that I’d only have sons, and that I’d return to Bulgaria the following September. And she told me to come back to see her. I told her, ‘I’m not coming back; I’m taking a break. I won’t be singing next year.’”

She continues.

“In the meantime, I met Boba; we started dating, and I realized my plan to take a break. My manager Raka respected my wish and gave me space and time, but one day, he decided to call me while I was at a hotel in Opatija, relaxing by the pool. I had told them not to disturb me because I was there incognito. But he was so persistent that they finally ran a cable from the reception to the pool. ‘I know you said not to call, and I don’t need anything from you, just relax, but please promise me that we’ll go to Bulgaria on the first of September.’ I think I said yes just to get him off my back. Then I realized—Baba Vanga told me I’d come back in a year!”

“Let’s not skip over Slobodan Zivojinovic Boba.”

“When I met Boba in my late twenties, that was the first time I truly… you know… fell in love.” As she says this, cheers and shouting begin to come from the kitchen. Her friends are listening, after all.

“Don’t shout!” she laughs and continues. “When he showed up, I realized that was what I had been missing. My bandmates would go back home to their families. And I would go back to an empty apartment. That love gave me a new understanding that what I was going through was too much for one woman. I didn’t want to be Lepa Brena twenty-four hours a day—cheerful, happy, a singer, a public figure.”

“Did he bring you the balance you needed?”

“Yes. Because he was a global star at the time and knew what I was going through. I simply felt I could relate to him. He had a childlike joy for life. He completed me.”

“You were our celebrity couple even before David and Victoria on the world stage!”

“When he took me to London to pick out a ring, the jeweler brought such a big diamond that I thought they were joking with me, like he’d taken it from the chandelier.”

“And let’s not forget, a Dior wedding dress.”

“I remember doing two concerts a day, slimming down from 85 to 64 kilograms, and I was as slim as a model. I fit into the dress easily. But journalists didn’t let me enjoy that moment, writing that I’d removed ribs. I couldn’t understand why they wrote that, knowing how natural and beautiful I was.” She laughs heartily, making everyone in the room smile.

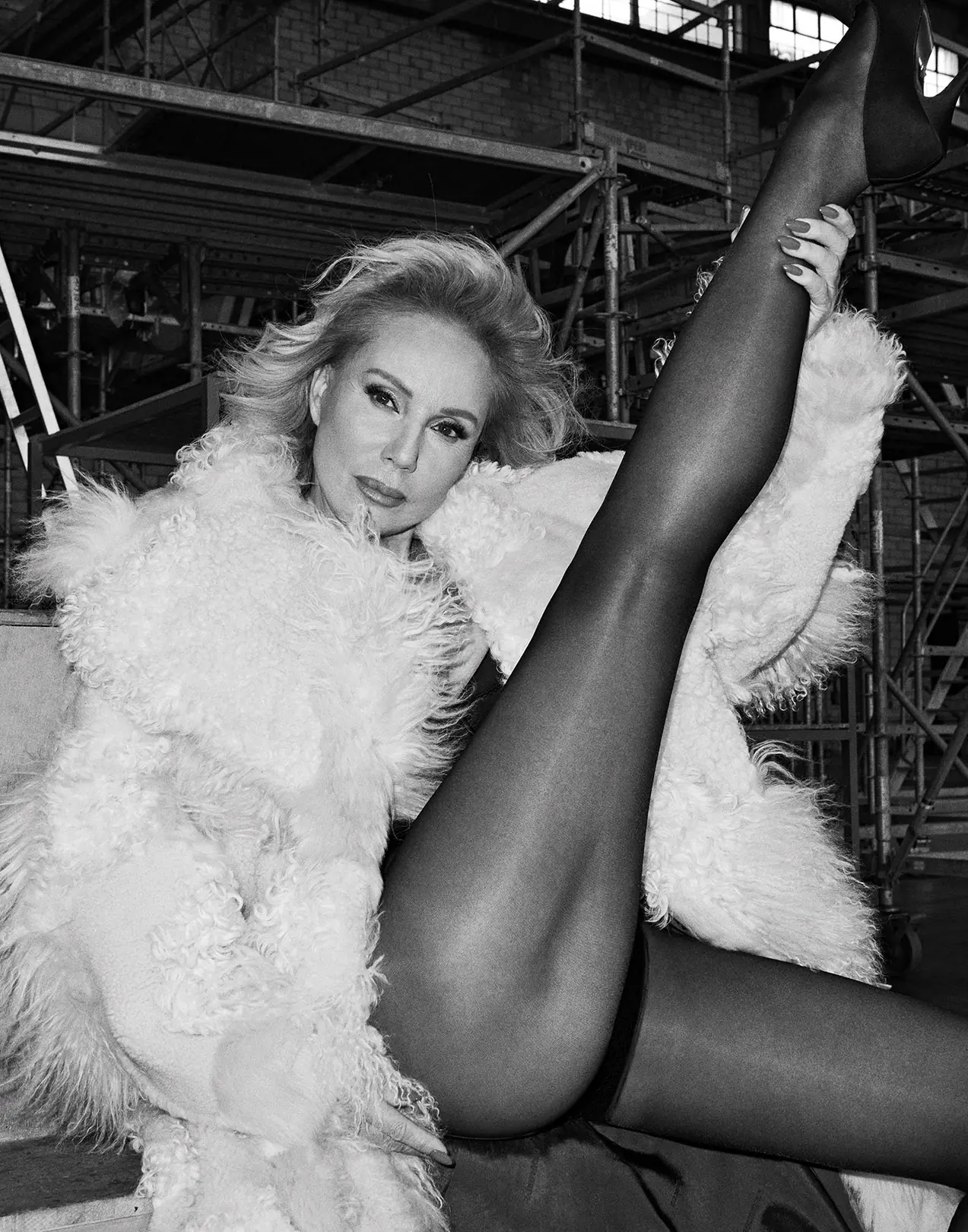

“What will people say when they see you in these runway sizes for this editorial?”

“I’ve always been naturally attractive.” We continue laughing, and she decides it’s time to order food. “I’m on a protein diet right now. But I’m not excluding wine! That’s entirely natural!”

“When it comes to the shoot, let’s be clear, you’ve set the bar for me. But seeing the enthusiasm you put into all of this gave me the strength to persevere. Remember how I kept telling you, ‘No giving up!’”

Lepa Brena has shown, both before and during this shoot, that she’s a rare professional. After the mood board was made and the shoot agreed upon, she completely surrendered to the process. Not once did she act like a diva during the shoot.

“I recognized you as my own. And when you work for family, you give everything—the last drop of love, the last ounce of strength.”

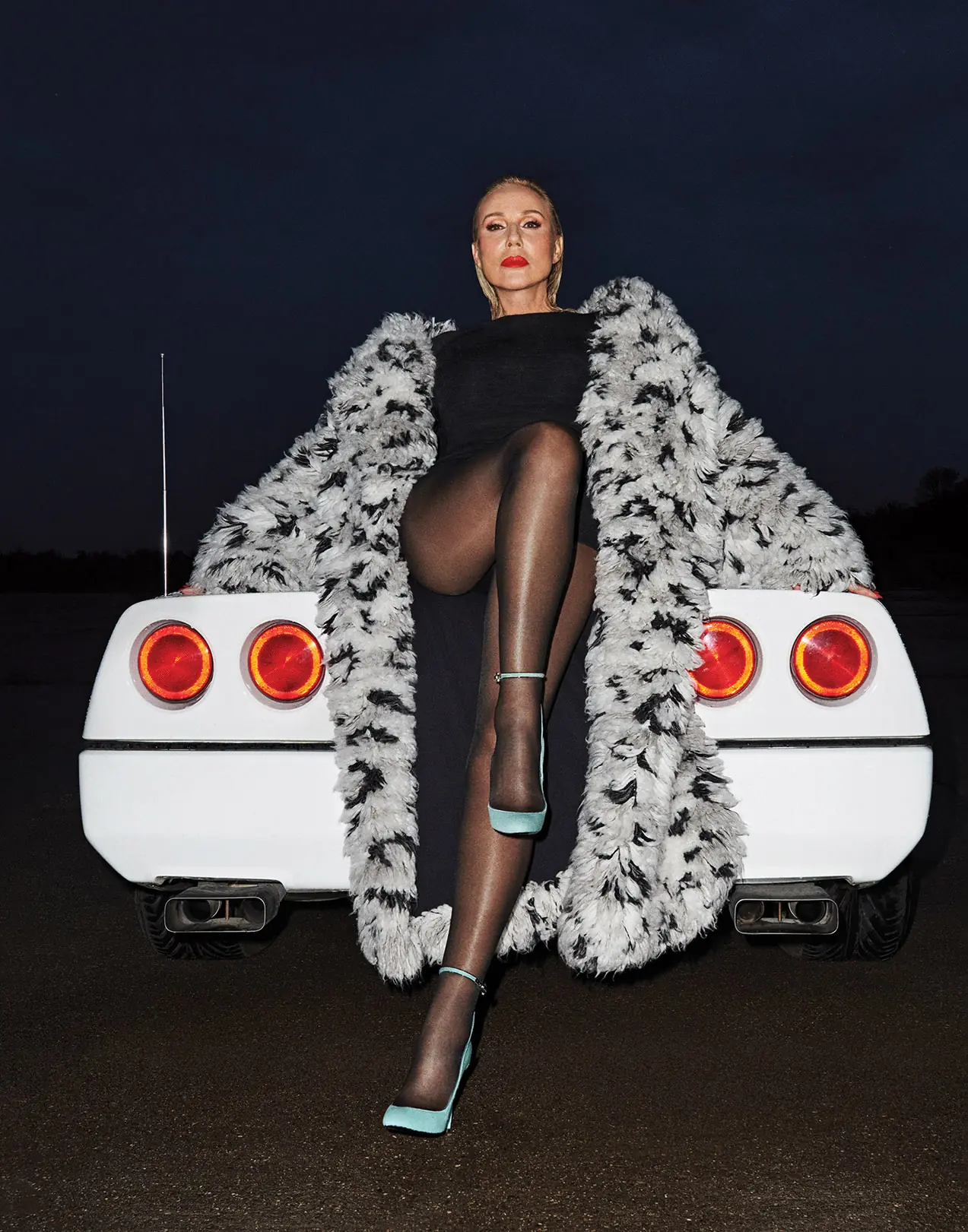

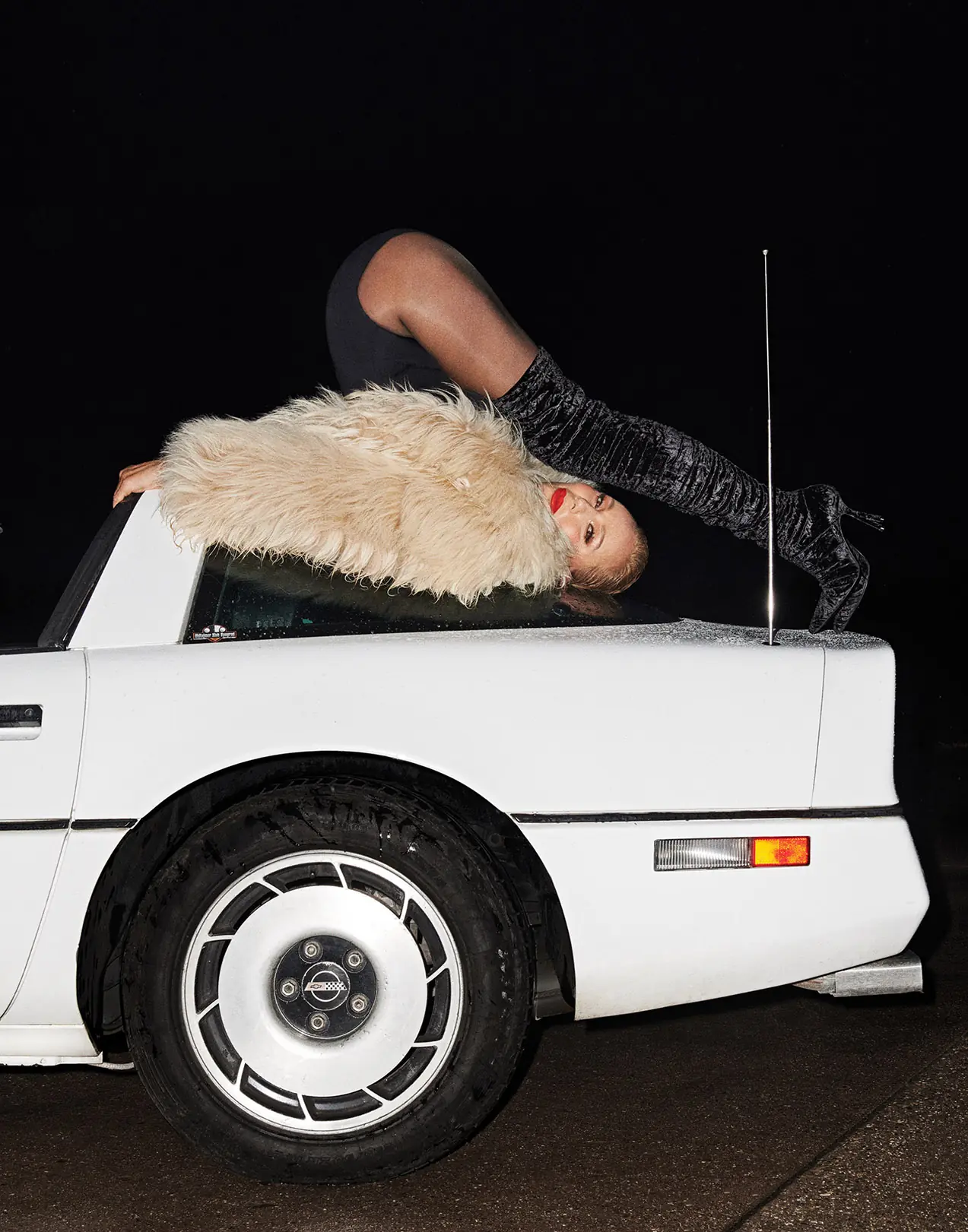

We can attest that it was truly so. On one of the four days of shooting at the airport, after 12 hours, it began to rain, and Lepa Brena, on the car, swung her legs over her head on the hood.

“That photo is incredible,” I exclaim.

“I know I used to be a hot babe, but even now, I’m not that bad.” As we laugh, we remember how nervous we were while she was doing acrobatics during the shoot. “I used all my yoga skills during the shoot, but after I did it, I just thought: ‘Hey, woman, you’ve fallen so many times, hurt yourself, what are you doing?! Act normal!’ But you and your energy swept me up.”

When we say that Lepa Brena was the symbol of Yugoslavia, we don’t mean a political figure—she was simply a symbol of the idea of unity, a symbol of “let’s love each other.”

“I understood Yugoslavia as a little European Union—we had one currency, one president…”

“One Lepa Brena!”

“One Lepa Brena!” she repeats, laughing.

“Do you ever sing your songs when you’re alone?”

“I try, when I enter my home, not to be Lepa Brena. To hang her up on a hook. But I love singing traditional folk music. I love sevdalinka. I have several that are my favorites. She calls out to her friends in the kitchen: “Can we have a little more wine, please? We’ve run dry already!”

“If we go back for a moment to you being a symbol of the time, a time that eventually began to fall apart, did that add an extra burden for you?”

“There were so many beautiful moments in my life. But so many painful ones too. And as I said before—I wouldn’t want to relive them.”

And I ask her just one final thing.

“Are you thinking now about stopping singing? About hanging up the microphone?”

“Not anymore. Only now, in a way, I’m enjoying it; I have ideas about what else I can do. I’m unburdened because I no longer have to prove myself. I can create without any pressure. If people like my voice and my song, that’s what makes me happy. Even if I sing just for one table where two people are sitting, it doesn’t matter to me. What matters is that I love what I do and that they love me.”

She stands up slowly and asks me to come with her to another room. There, photos of her family are arranged. She picks up a framed photo of her mother and father and shows it to me. Her mother wears a fitted floral dress, her father a tailored suit. “Look at them. They were farmers, yet they sat in the hay like this, dressed so well. She made everything for me. She made me who I am. Even that suit I wore for the yacht photoshoot—she made that. Imagine if she knew her creation would end up in a magazine like Vogue.” As she says this, tears start rolling down her cheeks. She returns the photo and continues, “You know, that plaid suit from the shoot—it represents everything I am. The symbol of my life. The symbol of the love I want to give people. That’s ‘Hajde da se volimo’ And I wore stockings, and shoes a size too small. With those stockings, two sizes too small!” she laughs. “But nothing was a problem for me. I stood on that catwalk in that suit, and nothing was a problem because I knew why and for whom I was doing this.”

Maksi patcwork bunda od vune, Dsquared2

I feel that, instead of a gift for her 64th birthday, this third meeting and that sentence she spoke are a gift to me. I am grateful to her for that because, through these photos, she has shown that everything I’ve written about her is entirely true and has justified all the reasons we chose her for our cover. I hope you will feel the love that Lepa Brena is sharing with you.

—–

Photography: Branislav Simoncik

Fashion: Petar Trbović

Creative direction: Stanislav Zakić

Photography Assistant: Darko Sretić

Hair: Milena Maršić

Makeup: Saša Joković

Makeup Assistant: Marija Stošić

Models: Marija Žarić, Jelena Simonović, and Nikola Bubanja

Production: Strahinja Đurčić

Location: Tito’s Villa “Galeb”