Forty years in Hollywood sounds like a serious tenure, almost a parallel life. Yet in a city where time is not measured in years but in blockbusters, scandals, and the films that shaped us and then disappointed us, it is just long enough to become an indelible part of the cultural collective, even if you have never stood in front of a camera. That is what the career of Lauri Gaffin looks like, a woman who quietly assembled the worlds that defined our childhoods and all those phases we thought we would have under control but did not.

Related: Bojana Nikitović Reveals the Secrets Behind the Costumes of Movie Blockbusters

When I think about the films I grew up with, from the icy, claustrophobic frames of Fargo to the neon pop chaos of Charlie’s Angels, I realize I actually grew up inside her sets. It never occurred to me back then that someone had to decide what every snowy road would look like, every wild gadget used by the angels, every tilt of a villain’s office chair. Today, now that I know how much creative chaos and how many micro decisions stand behind a single frame, I find it even more fascinating how Gaffin managed to remain almost invisible while being crucially important.

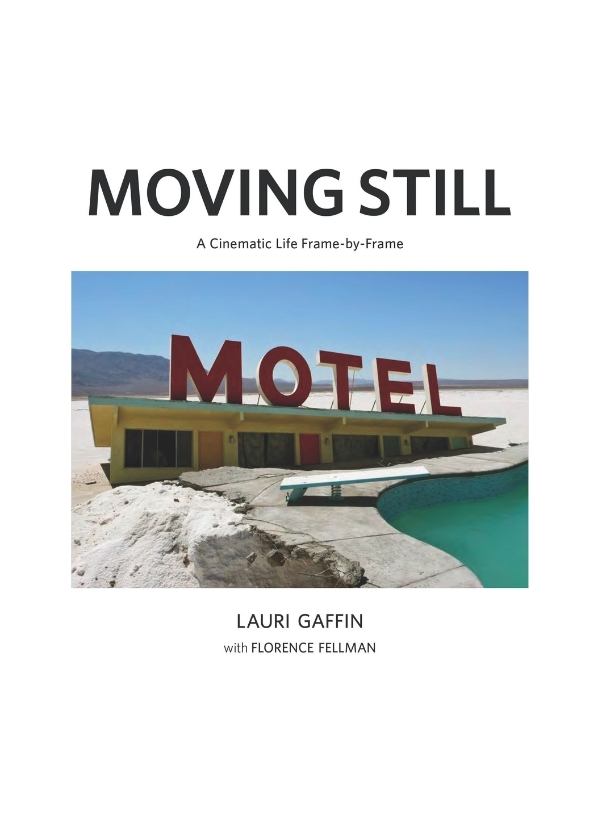

And who is Lauri Gaffin, really? A woman whose official title is set decorator, though it could just as easily be called shaping worlds that become part of our emotional archive. For years she quietly photographed everything that films never show, the moments between two clapperboard strikes, actors laughing when the camera stops, technicians repairing Mars in the middle of the Mojave Desert. All of this is now collected in the book Moving Still: A Cinematic Life Frame by Frame, which launched during Paris Photo.

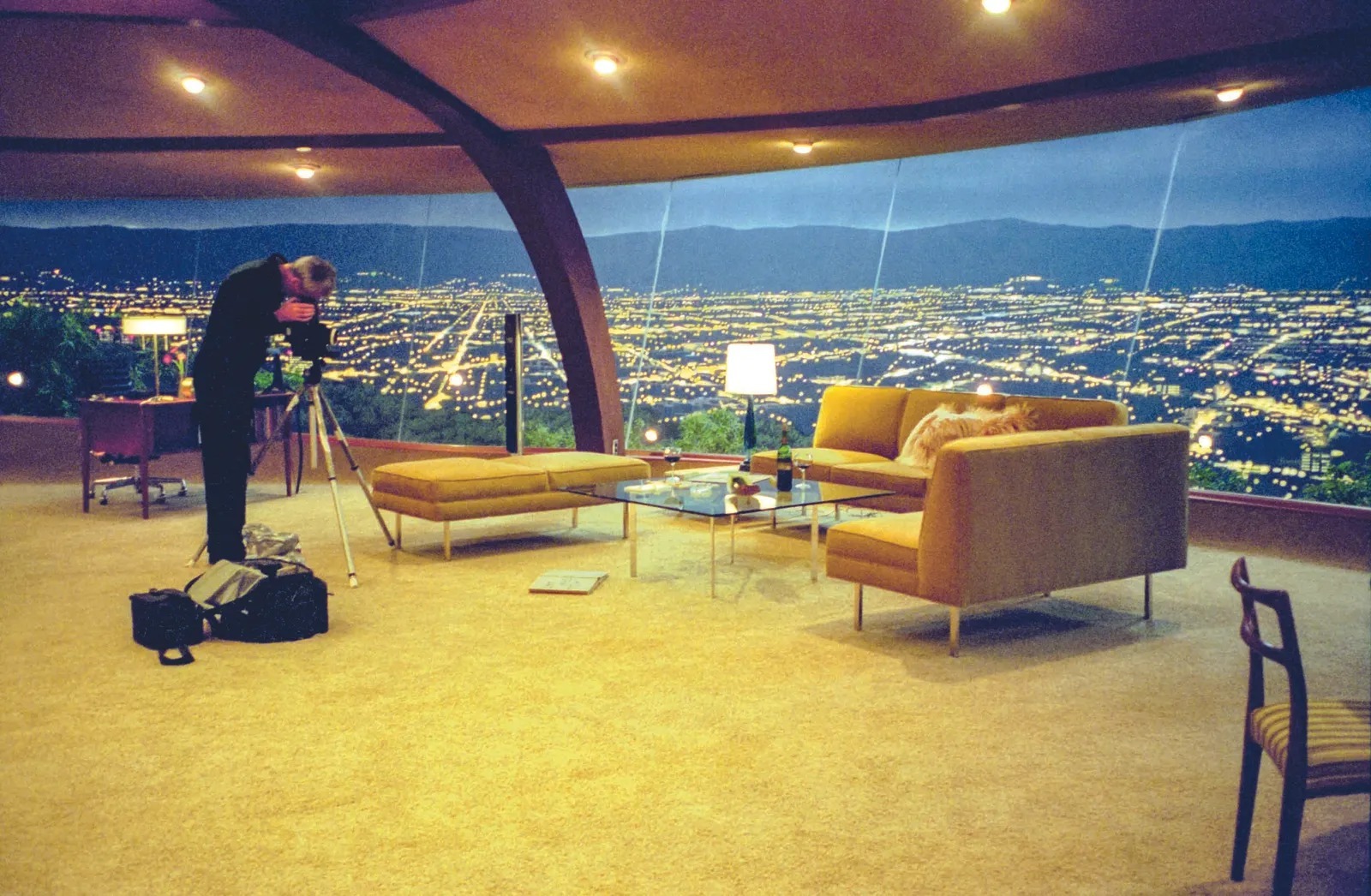

Through the photographs in that book we jump from the frozen plains of Fargo to the sticky swamps of Louisiana, then to the Martian landscapes of the California desert. We enter the organized chaos of the set of The Pursuit of Happyness, fall silent before the controlled madness of Iron Man, and at one point we stand right next to the crew leaning over a submerged airplane in Six Days, Seven Nights, as if we too might have to give a statement to the insurance company.

What Gaffin does is surprisingly intimate. Not intimate in the sense of look at the actors without makeup, but intimate in the sense of who truly stands behind the stories we devour. Directors, production designers, actors, costume designers, people who work sixteen hour days so that we can forget reality for two hours.

The book also records completely bizarre details, for example the enormous reptilian alien from Evolution left on the floor between takes as if it were a crumpled raincoat. Or the stylized, almost too shiny aesthetic of Charlie’s Angels, which looks as if it lives only on adrenaline and lip gloss. But Moving Still is not just a film artifact. Gaffin also inscribes her own story into it, caring for her parents, complicated relationships, the emotional weight of working in an industry that, despite all the Oscars and awards, does not joke about deadlines or expectations.

In the end, Gaffin achieves something few others can. She fuses spectacle with tenderness. She shows us the worlds we watched on screen and also the world behind them, vulnerable, creative, wild, messy, beautiful. This is a book about what life behind the scenes looks like and how, even there, someone can discover another form of art.

Moving Still: A Cinematic Life Frame-by-Frame