“If I weren’t an artist, I’d be a pop star.” Artist Karlo Štefanek, in conversation with Aleksa Jovanović, talks about how he started making art, his love for music, and whether “abroad” is really always better.

A little over a year ago, I began a rather unusual acquaintance that quickly evolved into what I’d call a highly productive friendship. Karlo and I started collaborating spontaneously—from exchanging compliments on each other’s work to long conversations about art, ideas, and personal experiences. Once we realized that, despite visual differences, our works were surprisingly similar at their core, it felt natural to begin creating together. That eventually led us to an exhibition. One of the pieces that emerged from that process was a performance/video work in which Karlo and I spent the night in a gallery—on February 14th, no less. Pretty fun, if you ask me. That night remained a kind of open-ended conversation that, I feel, is still ongoing. We had already touched on many of the questions Karlo explores in his work—about the body, identity, and space for queer art. This interview, conducted for Pride Month, is simply a continuation of that dialogue.

I’ve never experienced his work as cold, even if it might appear distant at first glance. Even less so as purely conceptual. I’d rather say that Karlo creates a space for vulnerability, uncertainty, and silence—one he doesn’t try to fill with explanations. The body, identity, the gaze of others and that inner gaze… all of it intertwines in his work, but without imposing a narrative. We talked about his practice, about how queer identity runs through his work, and about those in-between places where art and life overlap. And maybe most of all, about what happens when art doesn’t offer solutions, but gently leads you to a question you don’t yet know how to ask.

Design as a dilution of one’s own identity

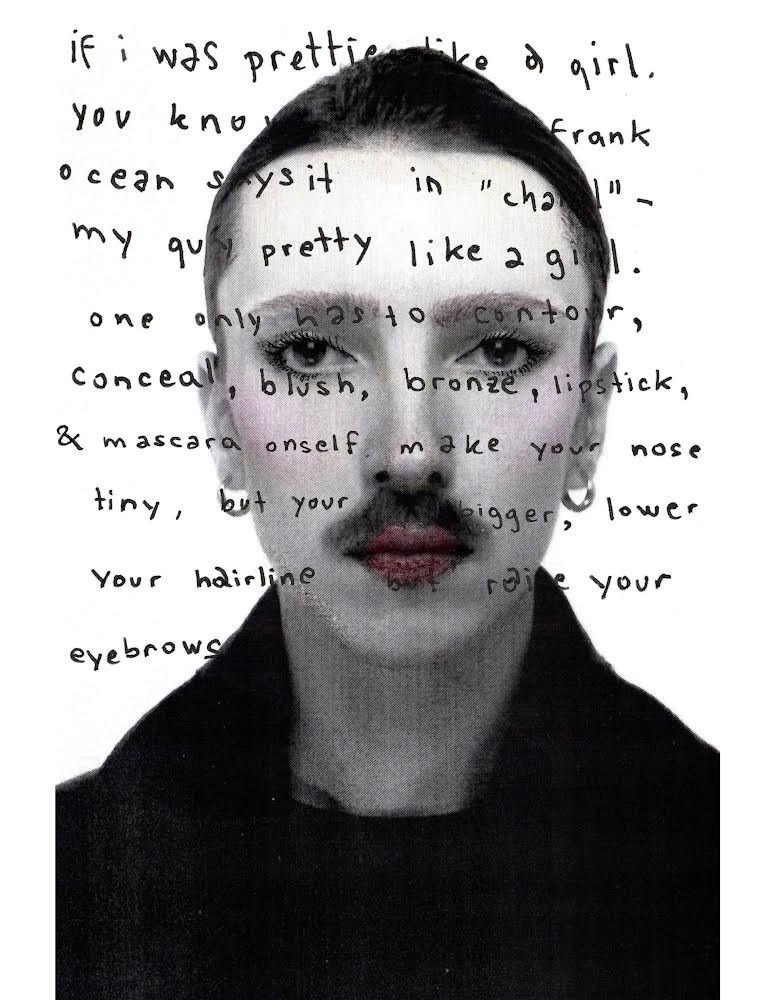

I wanted to start from the very beginning of his artistic journey—why he began making art and whether he remembers that moment. “It wasn’t a single moment,” he told me, “but more like a series of decisions to keep doing what felt natural. Still, it took me some time to allow myself to call myself an artist. I’ve always drawn and painted, and then I started dancing, performing, singing in a choir. Later on, I thought I would go into design.” “In fact, my first serious educational experience was at Parsons School of Design in New York, where I immediately fell in love with the design process. After returning from New York, I enrolled in a design program in Amsterdam. There, I soon realized that what interested me most was the very beginning of the design process—research and conceptualization—so I decided to specialize in branding. It was during those studies that I created the first piece in my self-portrait series Self-titled (2022–). In the series, I direct my own image through mechanisms like mystification and autofiction. Later, when I wanted to have an even more public and direct relationship with the audience, I began performing that self-portrait series through live performances. With those early performances, I returned to the younger Karlo, who had always wanted to be a performer. And once I became aware of that, I soon realized that choosing design had actually been a way of diluting my own identity into something with a safe, professional framework.”

I clearly understand what Karlo is talking about—and it’s something that comes through strongly in his work. The whole process of becoming aware of his desire for this vocation shapes his identity, and I believe the audience can feel that. That’s why the next question felt like a natural progression: about the works in which queer identity doesn’t appear merely as a theme, but more like a kind of pulse. Has it always been important for this to be a clearly present component, or did it naturally emerge through his visual language?

“First, I want to define what queer means to me. I don’t see queerness as a label for my fluid sexual orientation, but rather as a theoretical framework. That probably comes from my refusal to be placed in any kind of predefined identity box—or to speak exclusively to those already within the same one. In Zagreb, you don’t have to be gay to be ‘queer.’ Here, it’s enough to be unmarried, a single parent, or a boy wearing pink… In that sense, queerness doesn’t need to be explicitly emphasized in the work—it already shapes the way I look, feel, and choose what to show. Queer in my work isn’t decoration, it’s a lens.”

Since we’re on the topic of queer experience, I was also curious about the current state of the art world when it comes to queer artists. Is there more space, more support now—or is it still a struggle for visibility, just packaged a little differently?

“I’ve noticed that queer themes are becoming increasingly interesting and more widely explored, but given the current global situation—where the same content is more and more often being banned—it’s hard not to question the stability of that support. That’s why artists need to be as brave, loud, and direct as possible in their work. It’s no longer just about being seen, but about how we are seen and who controls the frame. That’s where the struggle still continues.”

Karlo’s visual language carries something that feels both gentle and direct. At times, it seems fragile—almost vulnerable—and then, in the next moment, brutally honest. That dynamic strikes me as a key element of his practice. I was curious to hear his thoughts on that—how important ambiguity and duality are in his work and overall approach.

“I’m interested in the moment when something soft becomes uncomfortable—and vice versa; when something that appears harsh actually embraces you. Gentleness and brutality aren’t mutually exclusive—they arrive together. Take, for example, my piece FAG, where I stage the act of shooting a gun at my own portrait, using a bullet engraved with a word that haunted me my whole life. Someone might initially say it’s an aggressive work—and yes, the act itself is undeniably violent, and the video I exhibit includes the jarring sound of a gunshot playing on a loop. But tenderness lies in the details, if someone chooses to see them. That self-portrait, for instance, was filmed right after I’d been crying. It’s also an act of reappropriation, where I’m finally the one in control—the one destroying the word, freeing myself from it. I think a lot about how to present emotion without turning it into spectacle. What matters to me is that it’s portrayed the way it actually appears in real life. I don’t shy away from reality, even when it’s harsh, uncomfortable, or hard to digest—that’s exactly where the fragility you mentioned comes from.”

Now that it’s Pride Month, it feels like suddenly everyone wants to “celebrate queer identity”—media, brands, institutions. That attention appears once a year and then somehow fades away. How do you see it? Do you think this kind of temporary focus can actually help artists, or does it sometimes feel like it distracts from what really matters?

“I’d rather not be ‘celebrated’—I’d rather be truly listened to. I don’t have a problem with attention itself, but I do have a problem with the conditions under which it appears. My identity is not a ‘promotional campaign.’ But at the same time, I understand that visibility can help younger people recognize themselves more easily, especially in a region with so few publicly queer figures—and I don’t underestimate that. In art, though, it gets even more complicated.”

There’s a risk that queer artists become fetishized or decorative—or that we’re expected to exist only within themes of trauma and sex.

“I mean, look—we’re doing this interview for Pride Month, which already says quite a bit. On one hand, I’m grateful to be given space. On the other, I’m fully aware that this space comes as part of a moment. My identity is recognized as relevant, but also as a potential tool. My art deals with identity, so this kind of exposure is, to some extent, inevitable. Still, I don’t necessarily see it as a bad thing. It just requires a very good filter. It’s important for me to stay aware that I’m not being invited because I’m the only one like this—but because there are still far too few of us at the center… And it’s not like we have nothing to say once June is over.”

As an artist, there are certain works that mean a great deal to me. They’ve helped shape who I am, helped me position myself more clearly within the art scene—but perhaps even more importantly, they’ve allowed me to locate, in my own mind, who I am, what I want from art, and why I even need it in the first place. Karlo had already mentioned a few of his own works, so the question of whether he’d had a similar experience naturally came up next. Is there a work that holds particular significance for him? Perhaps because it helped him resolve something personal, or because he finally felt he was able to express something that had long been simmering inside?

“The work I’ve been thinking about the most recently is called 139 Letters to Noa Marlo. It was created last year, during what was supposed to be a 139-day stay in New York—the longest I’d ever spent there. At that time, communication had ended with someone I loved and had lived with for years, Noa Marlo. Instead of conversations, I started writing him daily letters. Alongside each letter, I took a self-portrait in the garden where I was staying at the time, as a kind of diary—those portraits track time, the changes in nature, and in me. I never sent the letters. They were first exhibited in Groningen—where, quite unexpectedly, Noa himself showed up. The piece consists of the letters, performance, and photographs, and it will soon be presented as a publication. Recently, I shared some of the letters with other artists whose work resonates with their content, and from that came a film that brings together their video interpretations. Although I describe it as autofiction, this is probably my most intimate work so far.”

Since Karlo is, so to speak, torn between three cities—New York, Amsterdam, and Zagreb—which sounds like an ideal balance, I believe it also comes with certain challenges alongside the obvious advantages. In such a busy lifestyle, it seems to me that finding peace, fitting in, and calling one place home isn’t easy. These three cities are completely different—not only in pace of life but also in culture, approach to art, and everyday life. I was curious how all of that affects a person. Is it really better outside the Balkans? Are there more opportunities? Because here in Belgrade, it often seems like “abroad” is easier: more content, more support, greater possibilities for quality artistic production and exhibition. So I wanted to hear how it looks from his perspective. Does Zagreb influence his work? And is it really better somewhere else, or is it just that old story about the grass always being greener on the other side?

“I left Zagreb when I was eighteen. Growing up there, what inspired me most was the desire to leave. And when I finally arrived in the so-called West, I realized the grass really is greener—but only because it’s fake. That disappointment was a key moment in shaping my worldview, including my view on art. My relationship with Zagreb has always been tense, and when you leave a city with unresolved issues, sooner or later you have to come back. For me, that return doesn’t mean reconciliation—it’s more of a constant confrontation. And there’s huge creative potential in that. It’s easier to be an artist somewhere else, where no one knows you. But that’s exactly why Zagreb is my greatest challenge—because here, everything reminds me of who I was, and that stirs the deepest cracks. One part of my performance and self-protest Against Self, which I performed last June, was precisely an attempt to come to terms with that.”

I return so that I can leave; I leave so that I can return. That uncertainty feels closest to my definition of home.

“Today, Zagreb, Amsterdam, and New York form three different anchors for me. I was shaped in Zagreb, in Amsterdam I first felt freedom, and in New York I have family—so I return there whenever I can. In terms of the scene, Zagreb might not have a large number of contemporary performers in the field of performance art today, but it has that raw, deep, historically rooted something that intuitively draws me. In Amsterdam, there’s a strong focus on the relationship between technology and the body. New York is completely different; everything is theatrical, exaggerated, and often intentionally ‘cringe.’ I find all of that very inspiring. Actually, most of what happens to me takes place between these places. I return so that I can leave; I leave so that I can return. That uncertainty feels closest to my definition of home. Being a stranger here and there—or at least feeling that way—sharpens your perspective. You become a tourist of everything, including yourself. You look more carefully, notice more, and keep the world at a sufficient distance to actually see it.”

Since we mentioned Zagreb, I couldn’t help but recall our joint exhibition and conversation that evening. We talked a lot about performance and the role of the body in art. For me, the body is, above all, a means of communication—whether in painting, video, or performance itself. In moments of creation, I often see it as a tool, something through which I speak, but at the same time somewhat separate from. I was curious if Karlo feels the same. Does his relationship with the body in his art change? And more broadly, how does the relationship with one’s own body evolve over time? It seems to me that this relationship changes as we grow, and I’d say it’s even more complex, intimate, and political for queer artists.

“The body is everyone’s first language, and at the same time the most uncertain tool. In performance, my body is both my instrument and my opponent. And I don’t always know how to handle it. I know how to abuse it, neglect it, sabotage it. But before every performance, without exception, I prepare my body. Sometimes I fast for days before the show, bathe in silence and darkness, get a massage if I can. All to align it with myself before I exhaust it again. Recently, in the performance Something Like Time (In the Event Of), I performed completely naked for the first time. That act was not a provocation, but an organic continuation of the concept I wanted to explore fully—it was simply the only way to fully embody endurance, exposure, and vulnerability. The performance lasted four hours—only the sound of a metronome, my counting, white chalk, and my own skin. Sometimes on a dusty floor, sometimes on my toes, sometimes running from wall to wall—I left traces of time across the space and on myself.”

Something like time (In the event of), performance, 4h, Self-titled (2022-), 2025

“The body in performance is my way of reclaiming ownership over myself—not ownership in terms of power, but responsibility. There are days when I can’t bear to look at it. There are days when I celebrate it. I don’t believe in pure acceptance, but in the body as a constant zone of negotiation.”

Another big struggle that, I believe, all artists face within themselves—I certainly do, and I assume you do too—is dealing with themes that are important to us but that we still haven’t managed to “capture” in our work. As if they’re always there somewhere, present, but always just out of reach. Is there such a theme for you? Something close to you, but that hasn’t yet found its form in your work?

“Identity. Although it may be the only thing I constantly work on. Maybe precisely because of that. I try to attack it from all sides—gender, nationality, sexuality, religion, language, time. Identity has to be constantly dismantled and reassembled to be real. Autofiction and performance can escape singularity the most, and it seems to me that identity is the freest there. I try to understand myself, but only up to the point that won’t block the work. Because too much self-awareness is sometimes the worst enemy in creation.”

I know Marina Abramović is a huge inspiration for both of us—we keep coming back to her in our conversations. But who else do you follow? Are there artists, contemporary or from the past, who inspire you? Or maybe simply calm your thoughts?

“From artists of the past, Egon Schiele, Louise Bourgeois, Joseph Beuys always come back to me. Of course, Marina Abramović and Mladen Stilinović. And then Andy Warhol and Felix Gonzalez-Torres. I’m quite late to the party, but my recent discovery is Sands Murray-Wassink. His work is messy, gentle, strange, beautiful to me. My Vlasta Delimar is always important to me. Among younger regional artists, I especially appreciate Ilja Simin, Marlen Ban, Ines Borovac, Maja Simišić—they’re different, but they all have something unfiltered in their work, and I love that. On the international scene, I follow Joan Horrach, Billy Morgan, Benjamin Francis, Nicholas Sanchez/Wonderful Cringe, Jens Huls. These are all artists whose works seem to come from some kind of unrest.”

Finally, something that’s often on my mind and that I personally love talking about—music. I know it’s important to many, but in the queer world it definitely has a deeper, more significant role. As a space for identification, liberation, escape, but also community. Has music influenced you in forming your identity, in your work? Are there musical stars you keep coming back to—visually, emotionally, or however?

“My mom was the first to play me Madonna’s videos. Later, Lady Gaga. I grew up with these women who weren’t just talented, but clear, unstoppable, smart. For me, pop divas were the first lesson in fame, iconography, performance, and control. If you stalk me on Spotify, you’ll see I have a playlist for every occasion. Sometimes I even create playlists for specific works. Music is always playing in my studio. I always sing in the shower. If I weren’t an artist, I’d be a pop star.”

Photographs: David Bakarić

Creative and Technical Production: Marlen Ban

Location: Autoelektrika Štefanek

Fashion: VICKO RACETIN Spring/Summer 2025 & Spring/Summer 2024