An exhibition capturing the bittersweet chapter of life we remember with nostalgia

Tara ĐukićNovember 5, 2025

November 5, 2025

Two girls are laughing and playing. Posters on the wall. Dolls on the bed. Hair clips in their hair. First nights out. First competitions. First crushes. These scenes take me back to a time of unrestrained freedom, carefree days, endless play that made time and space disappear. My room was like a playground, a small city where dolls lived in their Mattel houses — living a life that even Instagram would envy today. No obsession skipped me: from sewing clothes to collecting stickers, diaries, and magazines. I could invent, imagine, and direct anything in my head, and then live inside that fantasy for days. Completely untouchable. But when I had to step out of that world of childhood into the world of girlhood, I experienced it as a violent act. Suddenly, it was forbidden to dance in the rain, laugh out loud, sleep late, talk to objects, chase shooting stars. Where exactly does that transition begin? Do we decide that ourselves, or does society? And is girlhood just a passing phase — or also a state of mind, a feeling, even an aura we carry? The exhibition Girls. On Boredom, Rebellion and Being In-Between at MoMu in Antwerp this fall brings together interdisciplinary works by photographers, visual artists, costume designers, and filmmakers, exploring all the beauty and complexity of girlhood — from how our childhood has been represented and remembered, to how it shapes visual culture and fashion.

In the canonized history of Western art, girlhood has often been portrayed as a fleeting stage: tender, naive, in transition. As the eternal muse, the young girl in art history was anonymous — a silent subject, someone’s daughter. She plays the piano, holds a kitten, or properly folds her hands on her lap: her posture and attributes signal virtue and innocence. No one disturbs her; she simply exists. “Obviously, doctor, you’ve never been a thirteen-year-old girl,” says a line from Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides, perfectly encapsulating the nuances of growing up as a girl.

The Virgin Suicides

Art that places girlhood at its center is often dismissed as sentimental or intellectually shallow. But such trivialization overlooks the emotional, psychological, and political depth that this theme can offer. Through the eyes of the artists presented in this exhibition, girlhood is more than a subject — it is a way of seeing, remembering, and imagining. A space of reflection, stretching from the pain and suffering inherent in female existence to the magical and joyful bond that quietly, yet profoundly, connects us all. Curator Elisa De Wyngaert chose to include and highlight one element that represents the essential state of mind of a young girl: her room — a place that guards all her restlessness, questions, and visions. Perhaps one of the most iconic rooms in cinema is the one that imprisoned the five Lisbon sisters in The Virgin Suicides. At the exhibition, that very room has been reconstructed — a space that contained not only all the anger of the world but also all its boredom, a double-edged sword for the young mind, a catalyst for either the most creative ideas or an uncontrollable fear that triggers the desire to disappear.

Two other rooms come to life through the works of Jenny Fax and Chopova Lowena. The first recreates her European-style room in Taipei, a space that hid not only her OCD habits but also reflected her mother’s taste more than her own. The second interprets a shared space between two girls who met only at university — yet through what they created together, it seems they had once inhabited similar worlds in childhood.

Petra Collins and Jenny Fax, I’m Sorry, photo by Fish Zhang

Eimear Lynch, Girls’ Night

The exhibition is divided into three main conceptual parts — boredom, dream, and coming of age — exploring how these ideas reflect on girlhood and how they have been represented across different media and disciplines. From sculptures such as Edgar Degas’s Little Fourteen-Year-Old Dancer, to works by artist Sofia Lai created specifically for the exhibition, and paintings like Memories by Alice Neel, pieces by Arise Yoshioka, and photographs by Fumiko Imano and Roni Horn. Fashion also plays a significant role, with garments by Simone Rocha, Maison Margiela, Ashley Williams, Raf Simons, and D’heygere, as well as various historical iterations of white dresses — worn for baptisms, communions, and weddings. It seems that the life of a girl is defined by white fabric, whether by choice or by imposition (I never liked it); the exhibition leaves this question open for debate.

Tina Barney, The Dollhou

This exhibition — through a selection of works by those who understand girlhood from the most diverse perspectives, as well as through conversations with real girls and women throughout the process — achieves a universal yet deeply personal understanding of the theme: all the contradictions between what it means to be a girl and how that experience is represented or interpreted by others. Some of the most moving works are those inspired by Louise Bourgeois’s performative costumes, particularly the apron from She Lost It, which reads: “I had to justify why I was a girl.” We must never seek forgiveness, or feel as though being a girl requires pardon — and we must never stop feeling joy in being women.

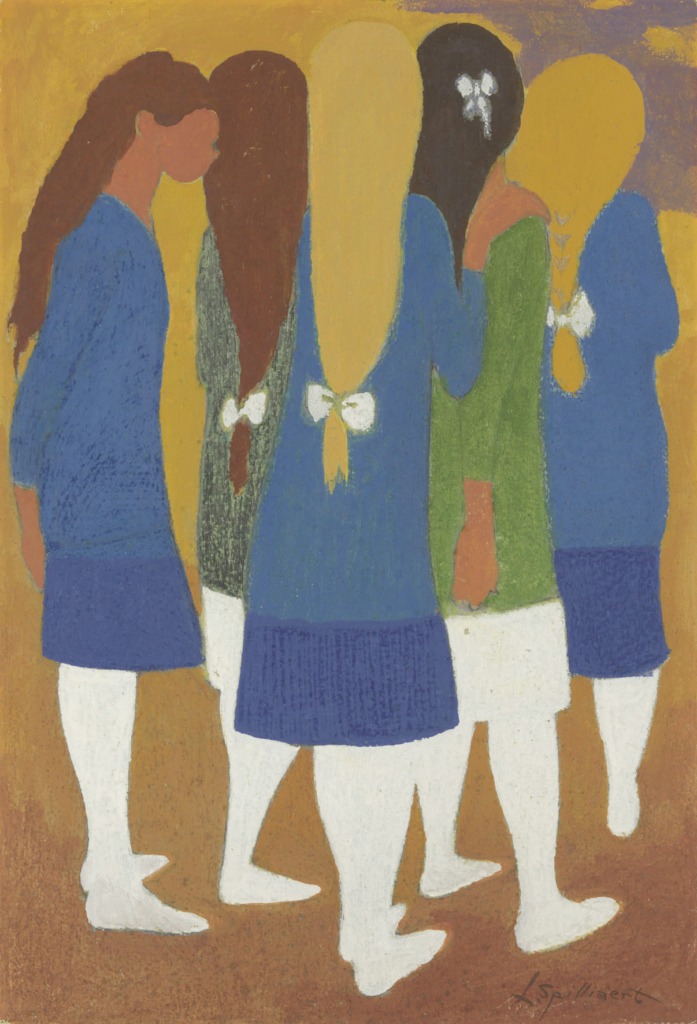

Léon Spilliaert, Girls with white stockings

Micaiah Carter, Adeline in Barrettes

The future is uncertain for all of us — shaped by gender inequality, poverty, conflict, and deeply rooted discrimination that denies us opportunities before we even have a chance to claim them. But the answer is resistance. This exhibition is a reminder that art, fashion, and culture — as forms of storytelling and representation — are essential for making our perspectives visible. Much like this year’s Photo Vogue initiative, which shares the same theme under the title Women by Women.

Jim Britt, Sisters

“For many female artists and designers, adolescence has always been a central part of creation — and as we grow older, it’s impossible not to keep at least one foot in those years. Many of the works in this exhibition aim to express precisely that: that girlhood is not something we leave behind, but a lens through which we continue to see the world. That’s what makes those years so precious,” says the curator for Vogue. The message is clear — never forget the girl within you, in all her delicacy, subversiveness, and fluidity; in the boredom that has now become a luxury, yet fuels creativity as a state of wandering or daydreaming, charged with the desire for transformation and self-growth. That is what keeps alive the spark that makes us truly living beings.

Girls. On Boredom, Rebellion and Being In-Between runs until February 1, 2026, at MoMu in Antwerp.