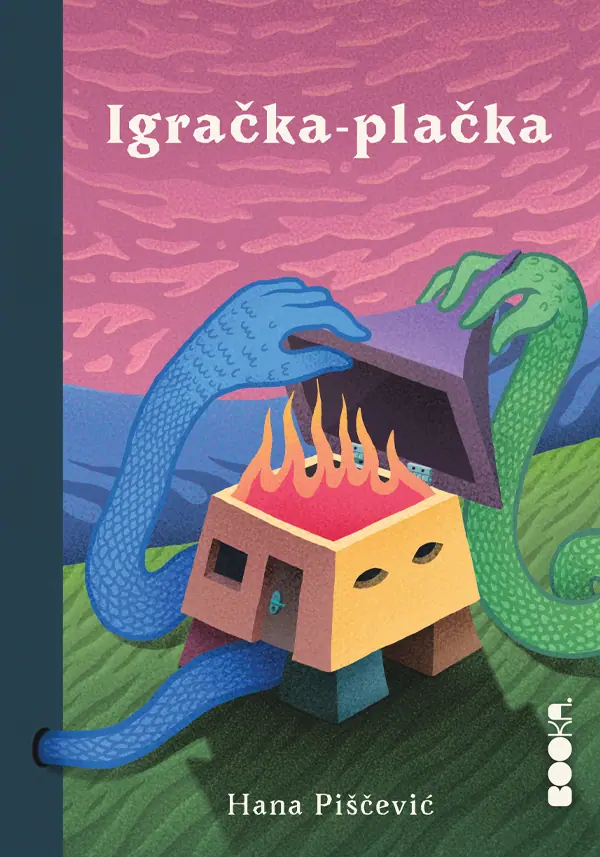

I don’t remember life before M. We were three months old when our mothers met on the promenade, both alone with their strollers. Her house was my second home; we went to ballet together, to kindergarten, and later to the same class at school. No one knew how to play like M did, or how to dance or philosophize about life like her. We were each other’s point of reference: T. was always by the book, M. was mischievous; T. should gain a little weight, M. should lose a little; we had the same model of shoes, birthday dresses, even New Year’s gifts. And in that childhood, marked by imagination, we experienced things those small shoulders could hardly carry. When I spoke with Hana Piščević, the author of the new novel Igračka-plačka, published by Booka, whose core is the story of two girls whose lives intertwine and whose growing up wouldn’t be complete without the other—without the one in whose eyes we see ourselves—Hana told me it’s a kind of unnamed first love.

The kind where, for the first time, we experience jealousy, happiness, betrayal, fear, and secrets. There’s a strong need to belong somewhere. Friends are the first mirror we look into, and often the one that shapes how we will love others for the rest of our lives.

The story begins when Savina receives a letter from Lu(ča) after years of silence. In her mind, the film begins to rewind, and frame by frame, she starts reconstructing their unusually deep, at times harsh, and profoundly delicate relationship. Their bond began in childhood, when children are both tender and cruel. It’s the time when we test limits, measure our strength, learn to survive, fall, and rise again. Every emotion feels intense, and time passes in bruises and scraped knees. We play, then get carried away, and suddenly everything becomes possible. When the girls, Lu and Savina, grow into young women, it’s as if they no longer know how to end the game that has, over time, become their language. They grow up in the same place but in completely different worlds, which makes things unequal from the start. Their closeness is constantly built in a space between pity and dominance, like two animals biting each other while, at the same time, licking each other’s wounds, Hana tells me.

Photo: Vedrana Vukojević

In the book, their interpretations of childhood differ, as if we’re witnessing the same events from two entirely opposing perspectives. We’ve all experienced that with our closest friends, whether we’re looking back on our hometown, school, or parents. I’ve often tried to “fix” or “correct” someone’s memory, or simply couldn’t understand where a certain perception came from. Some might call that the deceptiveness of memory. It has happened to me many times that while telling someone about my childhood, my sister would say, “Hana, you remember everything through rose-colored glasses.” And she’s probably right. I’m fascinated by how memory deceives, how it depends so much on the person it belongs to. I see it like a cassette tape onto which everyone records their own film. I believe it matters who we were, where we were, and under what circumstances when certain things happened to us. In the end, what we remember says more about who we are today than about what truly happened. Rashomon is a perfect reflection of that.

Sometimes we are defined by other people’s memories too. By their traumas and failures. Especially by those of the people who were part of our being during that long formative period, whose presence we carry with us even after we leave the shared shelter behind. I remember that shoulder to cry on that came a decade after we had lost touch, when I went through a sudden loss. And then, a few years later, the same scene in reverse. We didn’t need to reconcile, go back to the old path, or try to start a new one, everything except that one moment in time and the shared silence felt unnecessary. That silence helped us breathe more steadily, just like it once had. Yes, sometimes we’re so closely connected that we’re no longer sure what belongs to us and what belongs to someone else—where we end and the other person begins. Like communicating vessels, we spill into one another. Even today I still feel the sting of certain injustices that didn’t happen to me, yet I remember them as if they did. When you’re close to someone, their wounds become your own. There’s this invisible circulation of emotion between two people who grew up together, as if the same blood flows through them. Then the boundaries blur, and the membranes separating them become permeable. It’s not empathy or projection, but something else, I don’t know, maybe symbiosis?

Photo: Vedrana Vukojević

The novel’s very synopsis poses the same question: where are the boundaries of friendship? Those shifting, invisible, and porous membranes that should, at least in theory, protect us from others—and others from our whims and madness. And whether, and to what extent, the people closest to us remain a part of us even after contact is lost, when they exist only in unreliable memories and subjective praises or resentments. Is that unbreakable connection a source of strength or weakness? I ask her. Both, she says. Strength because you know you’re not alone. Weakness because you know you’re not entirely your own. The line between love and dependency is thin, and somewhere in between lies their relationship—one moment it gives you wings, and the next it presses down on you like a stone. I don’t think love necessarily ends, but destructiveness begins the moment we start hiding parts of ourselves or inventing others. When we want to be someone we’re not, or feel ashamed of who we are. As we grow up, small cracks turn into fissures, and fissures into holes. And maybe that’s the hardest part of adulthood—to recognize who is worth fighting for, and who you need to let go.

The novel is a tangible form of introspection—Hana’s, Savina’s, and Luča’s. She began writing it after the end of a long friendship, as a way to understand and come to terms with that loss. The more she wrote, the further she drifted from herself, and as the story grew, she slowly disappeared within it. Some friendships truly endure, but others continue out of habit, out of fear of loneliness, or from a sense of debt to a shared past. As if we’re afraid that, by ending them, all the previous years would lose their meaning. So we try to freeze time, to stay the same, to resist change. Only much later do we realize that with some people, growth simply isn’t possible—and that not every relationship is meant to last forever. Some connections existed only so we could become who we are now. And that’s all there is to it, she tells me when I ask about the friendships we keep maintaining in adulthood, even though we stopped being who we once were in them long ago.

Photo: Vedrana Vukojević

In that context, I turn to another important motif in the book—the abrupt kind of growing up, the one shaped and imposed by society, that happens when we don’t yet feel ready for it. Maybe we still wanted to play with dolls, to be held in our parents’ arms, to enjoy carefree moments of idleness. There’s a kind of metaphor in the story: the main character suddenly grows so tall overnight that she feels like she’s hitting her head against the ceiling. I’ll answer with an excerpt from the book, or rather, I’ll let Savina answer: “While she was trying to catch her own tail, I was trying to catch hers. I was short and undeveloped, without any curves, and from behind, I could easily have passed for a boy. Sometimes I thought that was why I was so wild, that the boy’s body I had been given was to blame for everything. Even though I was constantly moving, when I walked, I took small steps, as if I were in no hurry, so it always felt like I was lagging behind Lu. Only when I ran was I the fastest, but that was because I thought I had to run away. When elementary school was coming to an end, when the entrance exams were approaching, it was as if I suddenly had to grow up overnight, to stretch my body so forcefully that it could suddenly contain everything that belonged to adolescence. So I grew quickly, and in a few months I surpassed my peers—everyone except Lu, who by then had already gone too far ahead. My bones didn’t hurt, but my head did. While I was taking the entrance exam, I stared in confusion at my childish handwriting, those crooked letters filling the pages, and thought I was going to faint.”

Photo: Vedrana Vukojević

When she isn’t writing, Hana Piščević plays—or rather, she never stopped playing. As the creative mind behind the brand Pako Nao and through the way she approaches parenting today, play for her is a way of understanding the world, but also, I’d say, a way of preserving the child within her that keeps her alive. “My parents always let me do everything through play. By that, I mean sports, running around, hide and seek, dancing, camping, traveling… There’s no single definition for it. My partner and I try to pass that on through Pako Nao—that both adults and children should find time to play. Because play shouldn’t be a luxury, but a life jacket. A way to stay alive, to keep the world from becoming too hard.” When it comes to parenting, she adds, the idea is the same: “We believe there will be time for everything in life, and that for now the most important thing is to keep playing for as long as possible—to make it the main tool for survival before all the duties, school, and everything else.” In a way, through motherhood, she also looked deeper into her own introspection—out of fear of repeating her own or others’ mistakes. “I actually love going back, seeing who I was, what has changed. Of course, that brings a lot of guilt, self-criticism, and questioning, but if you stay with it long enough—but not too long—if you’re not afraid of what you see, it also brings acceptance. Of yourself, and of those around you. It helped me love all my versions—the combative one, the confused one, the vulnerable one, the too-loud one, and this current one, still trying to reconcile them all.”

Photo: Vedrana Vukojević

To end our conversation, I ask her whether the past can ever truly be reconstructed, or if every story about memory inevitably becomes fiction. Hana doesn’t have a definitive answer—but perhaps that’s the point. “I think memories belong to the person who remembers them, and because of that, in a way, they’re already fictional by nature. But maybe it doesn’t even matter what was ‘real’; what matters more is what that memory means to us today.”