I am inclined to believe that, of all forms of human expression, film is the closest to magic. It can seduce, enchant, take us into another reality, and reveal a new world. Yet it can also act as litmus paper for the world we live in. It can illuminate painful places, touch the neuralgic points of society, mark unmarked territories, criticize, question, and call out. In his text “Before the Subjective Mirror: I Pretend to Be a Member of a Generation,” Makavejev noted that a “phenomenon can have as many faces as there are eyes observing it. I didn’t say half as many, because each of us can have more than two eyes—say, a skeptical eye, an optimistic eye, a teary one, both the one saddened and disappointed and the one wet with tears of joy. It’s all very, very complicated.”

All those eyes are film—thousands upon thousands of films, including those of the Black Wave. That brief but fertile period opened each of these eyes and looked at reality unafraid to say what it saw. Ethically, politically, and aesthetically bold and progressive, this era is likely the most valuable cinematic legacy we have as a region, reminding us, should we ever forget who we are and what we are capable of.

That is why, “before the subjective mirror,” we returned decades back to the legendary titles of this era, from Feather Collectors to Monday or Tuesday. To recall and revive them—not out of nostalgia, but to think more critically about the future and to remember that the role of art is to awaken us from apathy, self-loathing, complacency, and even self-sabotage. The films of the Black Wave are courageous, experimental, alive, furious, erotic, political, raw, and deeply human. In a time when culture is under particular attack from repressive and regressive politics, it is worth remembering that film is not an escape but resistance.

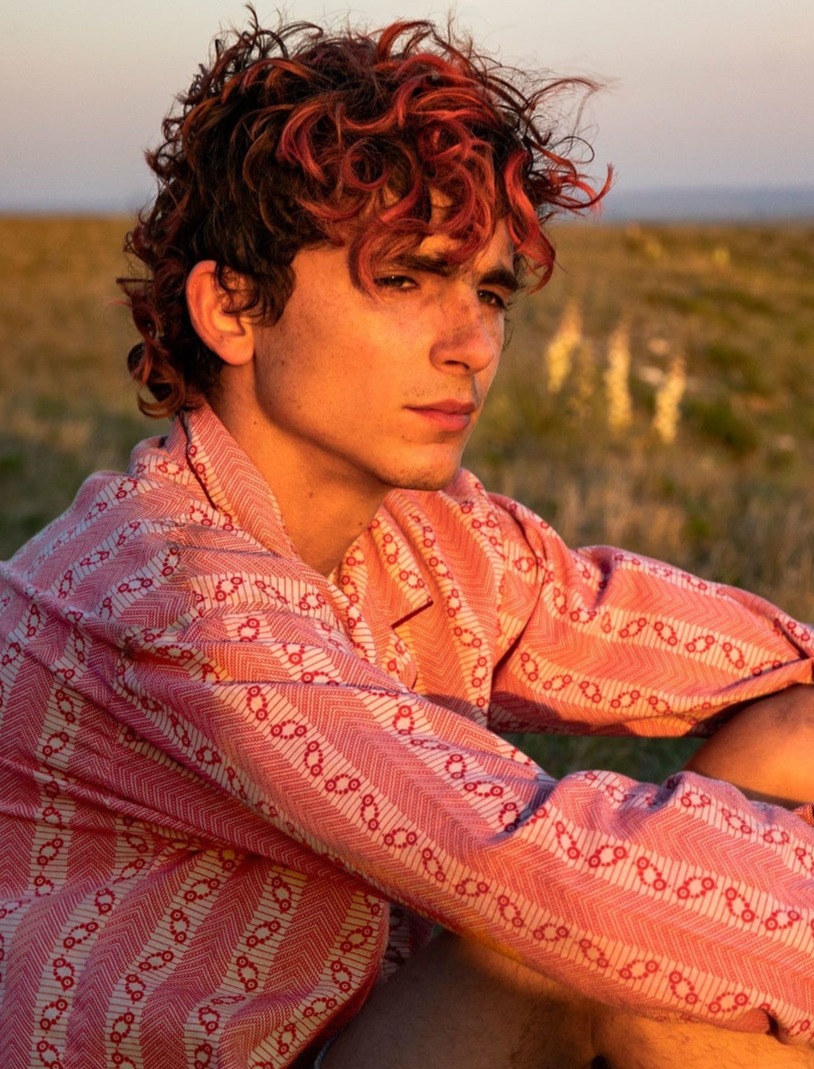

Members of the new generation of actors—Hana Selimović, Andrija Kuzmanović, Judita Franković Brdar, Slaven Došlo, Matej Zemljič, and Jovana Stojiljković—stepped into the roles of protagonists from the Black Wave films. We spoke with them about the state of society and culture, the engagement of cinema, the (non)conditions of work, how to achieve artistic courage today, and why, despite everything, film remains magical.

“Therefore, everything that happens to us, both good and bad, becomes part of our service. Every catastrophe, if you are creative and fail to turn it into your advantage in the next move, is your failure. So no one has the right to cry that their bread was taken away or that they were screwed over. That’s how it is in film. You simply have what you’ve swallowed—the fire you swallowed at one moment. That fire must shine in your next film and turn into a kind of sun. If you fail at that, well, tough luck. Then you have an ulcer. That’s fire too, only psychosomatic, and then you die and melt away.”

Dušan Makavejev, recorded by Živojin Pavlović, Belina sutra, Prosveta, Belgrade, 1983, p. 369

Slaven: I’m on my way to the closing of the festival in Bajina Bašta, but before we start—do you remember Bajina Bašta, Hana?

Hana: I do. I was on the jury last year—it was wonderful. I managed to avoid the parties until the Čola night; the rest is history.

Slaven: Right, I wasn’t there that year, but you replaced me—someone has to win the Golden Slaven (laughs), that’s the unofficial award. Jokes aside, this shoot and revisiting the Black Wave raised a lot of questions for me. Every time I return to those films, whether I watch them or just think about Yugoslav cinema, I’m struck by how much freer, bolder, and louder they were compared to what we have now.

Hana: What I find interesting—and what I’ve been thinking about—is how long it’s been since we’ve had something that could be called an artistic wave in our culture, and why that is. It seems to me that it has a lot to do with the fact that the opponent used to be clear, so the political and artistic response was also clear. Now that the opponent has become amorphous, our art reflects that as well. There’s a kind of absurd paradox where criticism of the system has become part of the system itself, rather than resistance to it. On the other hand, there are too many fronts to fight on, and in that chaos it’s sad that there’s no common current—and without it, there’s no wave.

Slaven: I’m not sure it’s about how concrete the opponent is. To me, it seems that, as a consequence of digitality, we now live in multiple realities. We must constantly be aware that each of us experiences our own reality according to the algorithm. In the past, systems of information at least began with the idea of a fact, but now it feels like we can’t even have a uniform response to what bothers us, because our perceptions of reality are deeply shaped by algorithms that feed us what keeps our attention. As for funding, art—unless it’s propaganda—cannot be a product of capitalism, and as such it’s perceived as excess or a kind of luxury. And I honestly no longer know how we got to that point.

Hana: What you said really interests me, it’s very Baudrillardian, about the end of grand narratives and the shift into simulacrum. That’s also what I mean when I say the opponent is amorphous. We no longer process anything drawn from direct experience. Everything is meta, but in the wrong way. What I find saddest, looking at it aesthetically, ethically, and politically, is how dangerous art once was. I would dare to say that today it almost isn’t at all. It’s become an extension of the illusion of democracy and freedom, where we can say anything, but it no longer matters what we say. It seems to me that film used to genuinely have an impact on a large audience, that the audience was more unified. Now our needs are so individualized that it has made it impossible for us to swim in the same current and create a wave together, which is paradoxical, because we are, in fact, all in the same water. Over the past year, artists have made an enormous contribution to this struggle, but as citizens. Why hasn’t that produced any kind of artistic response? I think this also speaks to a crisis of authorship, and we need to find a new form in which art can truly be effective, not nominal or decorative.

Slaven: The question is whether we’re not loud enough, or whether there’s just so much noise in general that everything can barely be heard. In the past, the focus on film and art in general was different. Now you have such a wide range—from TikTok clips lasting a few seconds to full-length films and they all exist in the same space. It’s very hard to say something and have anyone actually hear it. But, so we don’t fall into despair (laughs), I think the solution lies in looking our own blindness in the eye. If art has a message to convey, it has to find a way to shape it so that it communicates. That’s something people often forget.

Hana: I agree with that, and I really despise that kind of hermetic art that exists for its own sake and doesn’t treat communication as its primary goal. Theatre or film that shuts itself off becomes elitist. On the other hand, there’s also the horror of consumerism—the kind of complete pandering to elementary consumerism with minimal ethical or artistic reflection is, to me, just as dangerous a direction.

Slaven: True. But we have to find ways to reach a broader circle. Let me give you a non-acting example: take Sadhguru, for instance. His goal was to spread awareness about the importance of understanding the land and how we cultivate it, which affects countless other systems. He went on a motorcycle tour and even made a TikTok song. His aim was to deliver a message he found important, while understanding that the nature of reality today requires you to accept what’s happening in front of you and engage with it in some way. I’m not saying we should cater to the audience, but we need to understand our surroundings in order to address issues in a way that’s comprehensible. Finding new methods and approaches is essential.

Hana: The danger there is not to slip into populism, but yes, you’re right in a sense. We have to be aware that only about 2.5 percent of the population in this country goes to the theatre. On the other hand, I go back again to the Black Wave. Since every system shapes its own form of response, we need to figure out how, in such a fragmented system, to aim the most precise arrow. The Black Wave was largely a reaction to the irony of the “brotherhood and unity” ideal. Today, we don’t deal in ideologies, but in interests and profit. And within such a system, even criticism of the system has become a project. There has to be a way to step off that wheel. In the 1960s and 70s, those people were genuinely punished, censored, exiled. We’re not far from that now. The situation with the National Theatre is the most striking example of state repression against a cultural institution. It seems to me our response still isn’t strong enough.

Slaven: It sounds quite discouraging, how entangled everything is, and I often find it very hard to locate spaces of freedom and optimism. Honestly, I’m more and more inclined to look for them in personal action and existence.

Don’t Come Back the Same Way (1965), directed by Jože Babič Don’t Come Back the Same Way is one of the first Yugoslav films to address the previously taboo topic of interethnic relations in postwar Yugoslavia. It tells the story of a group of seasonal workers from what was then Bosnia and Herzegovina who travel in search of employment in Slovenia. Hana Selimović wears: a printed silk scarf, Chanel wool coat, Vaillant.

Hana: Collective uprisings are one of the most exciting things I’ve experienced in my conscious life, even though I haven’t yet witnessed a successful one. I’ll probably stay naïve until the end of my life and keep believing in that (laughs). Do you remember those days during the strike, when that big march happened? I rarely feel like I belong, but that day I really did.

Slaven: Yes, there was something truly special about those marches, every single one of them felt powerful.

Hana: I think that sense of belonging is exactly what we’re missing, and it’s something that’s built through communities of like-minded people. No matter how small those groups are, that’s clearly where we have to start. In that sense, I understand your idea of individual fulfillment, because you can rely on yourself, but I think the solution lies in nonviolent togetherness—in seeking out those who think alike, where people can talk the way we’re talking now.

Slaven: That’s what I mean too. But in that, you have to start with yourself, then with those you understand, and build your circles from there. The problem is, it’s sometimes hard to choose your battles or decide to make any sacrifice after so many failed ones. It’s hard to know where to begin, there are so many variables. People are carrying too much responsibility on their backs. Of course, in major events like the ones we’re living through now, it’s clear what needs to be done. There are certain lines, and once they’re crossed, people have a duty to react. But there’s just so much of everything.

Hana: Well, look—Gaza is happening. And we’re here analyzing artistic waves in Serbia. We all feel that there has to be some kind of response, but as Gorky said, “We are small people, and our strength is small.”

Slaven: I think that’s directly connected to what we’re talking about—the sheer amount of responsibility placed on ordinary people.

Hana: It’s proportional to what each person experiences as peace with their reflection in the mirror. Everyone is at peace or not with something, and that comes down to personal choices. As for artistic waves, they arise as responses to oppressive systems. We’re living through the consequences of many systems gone wrong. On the other hand, when you have bread to eat, you also have the “luxury” of thinking about the faults of social structures. Many don’t, and they’re focused solely on survival. Still, I hope that with some kind of distance—and victory—there might come an artistic response to this time.

Slaven: I completely agree, it’s just that everything is so insane. We’re out in the streets doing what the prosecution should be doing. The whole society has to mobilize in that way. What’s striking is that everything keeps happening all the time, which makes it paralyzing. AI is advancing like crazy, by 2050 there’ll be more plastic than fish in the oceans, the biggest labor market consists of drivers who are about to lose their jobs… There are too many fronts to fight on, and sometimes it’s all just overwhelming.

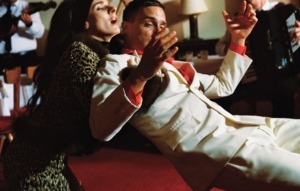

The Rats Woke Up (1967), directed by Živojin Pavlović A film about fleeting hope, disappointment, and the search for meaning, The Rats Woke Up is one of the most acclaimed works of the Black Wave, for which Pavlović received the Silver Bear at the Berlinale. Hana wears: a silk lace-trimmed midi slip dress, Dolce & Gabbana.

Hana: I agree, that perspective is both predictively realistic and a bit defeatist. Still, I believe there’s a kind of duty to do our best to act according to what we believe is good and right. The students have shown a model of organization that can work in many areas—collective action based on the smallest common denominator, where unity can exist despite differences.

Slaven: Yes, that’s our duty in a way, and maybe also the reason we started doing what we do. Without the belief that there’s at least a minimal shared ground to gather around, there would be no point in maintaining a dialogue through art.

Hana: Exactly. I wanted to be an artist because I’m interested in looking at the world around me—at people, phenomena, systems, politics, social conditions, poverty, and wealth. I want to look at all of that. When we close our eyes and hide from it, our art stops being art and turns into a kind of market product.

Slaven: I started acting for similar reasons, out of very personal motives. I was curious about what all of this is—who I am, what relationships and family mean, where I fit, what the system is. My main goal was to unpack all of that. I’d just go back to what we said earlier—I don’t think it’s defeatist. Of course, everyone should stand for their values, both in art and in life. I just meant it as a defense of people—I understand that they get tired, and I sympathize with that. I think we need a cooler head when reacting.

Hana: In political practice, absolutely. I’m not sure that’s good for art, though.

Slaven: I think it can be. When you look at things more calmly, you can sometimes find the answers. As for film and theatre, it’s all so complicated that I often don’t even know what my freedoms and responsibilities are. But in a personal, individual sense, I think everyone can find their own ways.

Hana: You’re completely right, because in our post-transition cultural landscape, the market doesn’t just sell art—it sells moral positions too. So being socially engaged sometimes becomes a kind of brand, and instead of collective struggle, you end up with aestheticized moral capital. In that sense, I believe we need to return to the idea that art must once again become dangerous and unsettling.

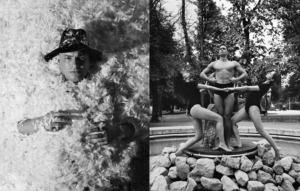

Left: Feather Collectors (1967), directed by Aleksandar Saša Petrović Set within a Roma community in a village in northern Vojvodina, the film transcends its local setting by addressing universal themes of love, interethnic, and social relations. It is considered one of the most significant works of the Black Wave and of Yugoslav cinema as a whole. Black cap, Valentino Right: Innocence Unprotected (1968), directed by Dušan Makavejev Constructed as a collage combining the 1942 feature film of the same name by Dragoljub Aleksić, documentary footage of Aleksić’s acrobatic performances, and archival scenes of Belgrade after the bombings, as well as appearances by Milan Nedić and Dimitrije Ljotić. Svetlana Slapšak has argued that it ranks among the best—perhaps the best—Yugoslav films ever made. Hana and Judita wear: short-sleeved bodysuits, costume designer’s archive Slaven wears: swimsuit bottoms, costume designer’s archive

Slaven: Exactly. Although I’d put it this way—it’s important to stand firmly for one’s libertarian values, which, in a society accustomed to violence, will inevitably be seen as something uncomfortable or even dangerous. I’m at an age where I often ask myself what I’m really doing (laughs). Some of those realizations are painful, but that’s what I mean when I talk about keeping a cool head. Seeing things as they are, trying to assess all my skills in order to achieve some sense of freedom through material security. Maybe it’s not even about freedom anymore, but rather about autonomy.

Hana: I understand, and I get your “cool head” example. At 38, I still haven’t managed to cool mine enough to secure that kind of autonomy. The only one that feels authentic to me is the one within the space of my own skin, and I try to protect that. But honestly, I think there’s hope. I traveled somewhere this summer, to a place that’s a true capitalist machine leaving no room for even minimal reflection. You either get richer or you survive. And the first day after coming back, I went to a protest. I just kept thinking about how many kind, civilized, politically aware, graceful, and brave people were there in one place. We don’t know the outcome of our struggle, but I believe that as long as we keep fighting, we’re in a healthy position.

Slaven: I find that incredible. When I actually see how many free-thinking people there are, willing to stand up for their values—it’s real. That line exists, we can see it, and through it, values can be established.

Hana: I think we often underestimate ourselves, even though we’re not insignificant. We just haven’t organized properly yet or found the right rhythm in how we respond. And not just reactively, as a counter to “their moves,” but proactively. I think now we have a chance to start setting the rhythm ourselves. I’m not sure to what extent or on what scale of organization, but I truly believe in small groups of people who share the same values. That’s how movements begin.

Talents: Hana Selimović, Jovana Stojiljković, Judita Franković Brdar, Slaven Došlo, Andrija Kuzmanovic, Matej Zemljic

Costume: Suna Kažić

Makeup: Irena Miletić

Hair: Milena Maršić

Set design: Sandra Subić

Set decor: Vitomir Kovačević

Production: Teona Milićević, Marita Bobelj

Assistant photographer: Darko Sretić

Costume and fashion assistant: Anastasija Jovanović

Makeup assistant: Nemanja Radočaj

Lighting: Etar Film

Special thanks to the restaurant Tri šešira, Maša, Steva and Stela, as well as the Milošević Sheep Farm.