I am inclined to believe that, of all forms of human expression, film is the one closest to magic. It can seduce, enchant, take us to another reality, and reveal a new world. Yet, it can also serve as a litmus test for the world we live in. It can illuminate painful places, touch the raw nerves of society, mark unmarked territories, and criticize, question, or call to action. In his text Before the Subjective Mirror: I Pretend to Belong to a Generation, Makavejev pointed out that a single phenomenon “can have as many faces as there are eyes watching it. I didn’t say half as many, because each of us may have more than two eyes—say, a skeptical eye, an optimistic one, a teary one, and that teary eye may be sad and disappointed, or wet with tears of joy. It’s all very, very complicated.”

All those eyes are film—thousands upon thousands of films, among them those of the Black Wave. That brief yet fertile period opened each of those eyes wide, gazing into reality without fear of saying what it saw. Ethically, politically, and aesthetically brave and progressive, this period is perhaps the most precious cinematic legacy our region possesses, one that reminds us—should we ever forget—who we are and what we are capable of.

That is why, “before the subjective mirror,” we looked back decades to the legendary titles of this era, from Feather Gatherers to Monday or Tuesday. We revisited them not out of nostalgia, but to think more critically about the future and to remember that the role of art is to awaken us from stagnation, self-contempt, complacency, and self-sabotage. The films of the Black Wave are courageous, experimental, alive, angry, erotic, political, brutal, and profoundly human. At a time when culture is particularly under attack by repressive and regressive politics, it is worth remembering that film is not an escape—it is resistance.

The new generation of actors—Hana Selimović, Andrija Kuzmanović, Judita Franković Brdar, Slaven Došlo, Matej Zemljič, and Jovana Stojiljković—stepped into the roles of Black Wave protagonists. We spoke with them about the state of society and culture, the social engagement of film, the (non)conditions in which they work, what it means to achieve artistic courage today, and why, despite everything, film remains magical.

“As such, everything that happens to us, both good and bad, serves our purpose. Every disaster, if you are creative and fail to turn it into an advantage in your next move, becomes your failure. Therefore, no one has the right to weep because they’ve been deprived of bread or because they’ve been screwed over. That’s how it is in film. You take in that fire you’ve swallowed at some point. That fire should shine in your next film and turn into a kind of sun. If you fail, well, too bad. Then you have an ulcer in your stomach. That’s also fire, only psychosomatic, and then you die and melt away.”

—Dušan Makavejev, recorded by Živojin Pavlović, Belina sutra, Prosveta, Belgrade, 1983, p. 369

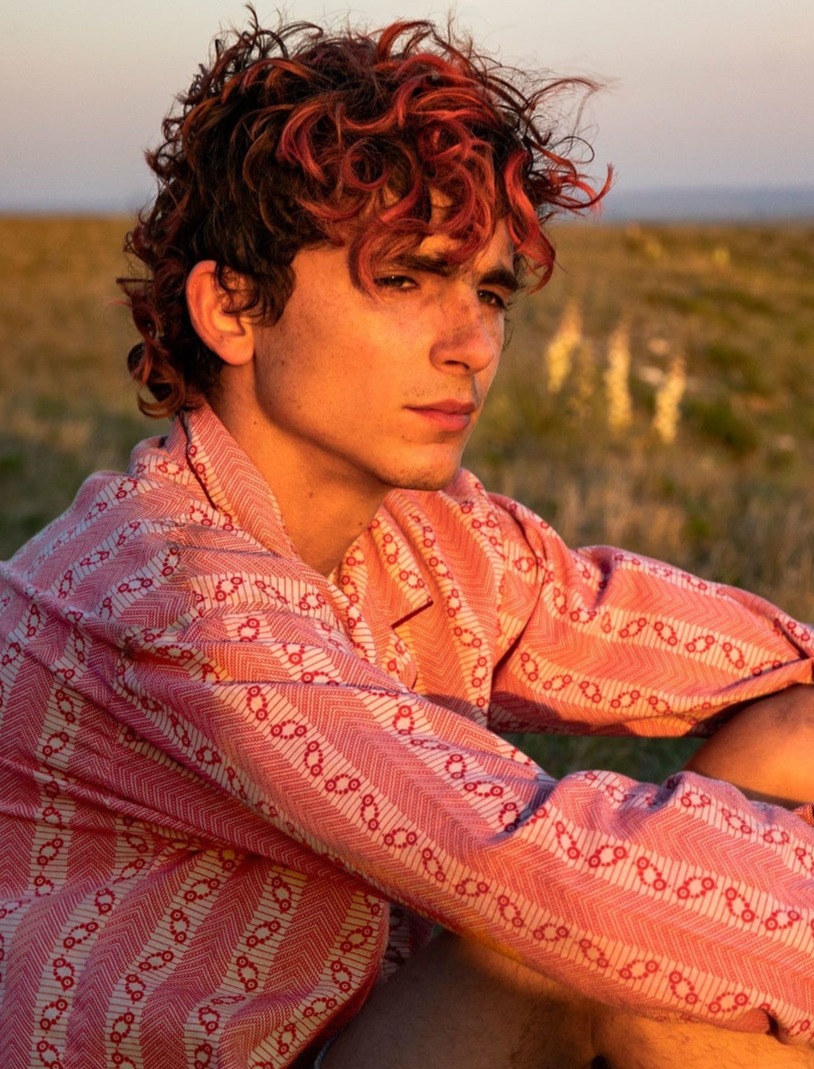

When I Am Dead and Gone (1967, Živojin Pavlović) A cult film of the Black Wave that follows a young man facing hopelessness and rebelling against a society that restrains him. Džimi Barka has become a symbol of a young man trying to find his place in a system working against him. Andrija wears: a wool-blend suit, a long-sleeved cotton shirt, and a printed tie from the costume designer’s archive.

Teodora: How did the two of you even meet? It feels like you’ve worked together on most projects (laughs), but where did it all begin?

Jovana: I think we met while filming Shadows over the Balkans, right?

Andrija: Actually, the very first project we filmed together, which you forgot about, was called Mio i drag. It was a pilot episode for a comedy about a group of young people living together. You were in your second year of the academy, just starting out.

Jovana: Oh right, I completely forgot about that! I was so young then (laughs). Especially because, when I think of us and everything we’ve done together, the first thing that comes to mind is always Morning Will Change Everything. That shoot lasted for months, and I’d say it was the most important one for us — professionally, personally, and for our growth. We filmed for several months and really became like a family. People often say that, even when it’s not true (laughs), but in our case it really was. We were driven by enthusiasm and felt we were making something that was truly ours. Shoots like that are rare. Personally, it’s the most important project for me, and I’d say for our relationship too.

Andrija: It was incredibly important for all of us. Morning Will Change Everything is probably my favorite project I’ve ever worked on. And now there’s Yugo Florida. Morning is special. It’s like the last breath of rock and roll. It has the power of Rods, but it’s much gentler, and the lightness of Fools Rush In. It’s the series that comes closest to growing up in Belgrade in the 20th and 21st centuries, and at the same time it has the magic of La La Land — you don’t really care when it takes place. The story, apart from Filip being an IT expert, could exist in any time. Morning is timeless. I truly believe that, though this is the first time I’m saying it out loud.

Jovana: Yes, and we kind of grew together with Tagić and Stanković, project after project. And now, years later, Vlada has made his first feature film. I remember how he called you to make sure you were right for the role and how that casting went (laughs). He called me for a small part, and I told him I wanted to take part in anything. I even said I’d be an extra just walking through a frame, whatever it takes, I just wanted to help. So we ended up working together again.

Andrija: What you did was really beautiful. A real bold move. It’s a big thing when actors who are used to leading roles decide to take on something smaller. It’s wonderful because everyone brings their own energy, and you show up to support and give strength, because the director asked that of you — to bring your own color. I like to say yes to everything I believe in, and I’d do the same if our roles were reversed. A colleague recently thanked me for coming to play such a “small part.” But nothing is small. Someone saw something in you, and that’s already something big. I don’t think insignificant roles exist. I always try to give the same effort and energy, to give my last bit of strength to those who’ve been working for months and believe I can help, even if just for a day. And thank you for doing that for Yugo Florida.

Jovana: I feel the same. It’s hardest for me when I give my all and someone else doesn’t, no matter how big or small their role is. As for this film, everything about it was deeply emotional for me — the summer premiere in Sarajevo, the fact that it’s Tagić’s first film, that you’re in every frame, and of course the film itself, the whole story. I hadn’t been to a cinema in ages, so the whole atmosphere really got to me. It was all so emotional, it completely hit me (laughs).

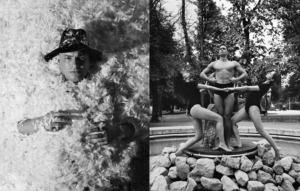

Left: I Even Met Happy Gypsies (1967, Aleksandar Saša Petrović) Set in a Roma community in a village in northern Vojvodina, the film’s story transcends its local setting, dealing with universal themes of love, interethnic and social relations. It is considered one of the most important works of the Black Wave and Yugoslav cinema. Black hat, Valentino Right: Innocence Unprotected (1968, Dušan Makavejev)

Created as a collage composed of the 1942 feature film of the same name directed by Dragoljub Aleksić, documentary footage of Aleksić’s acrobatic performances, and archival images of Belgrade after the bombing, as well as of Milan Nedić and Dimitrije Ljotić. Svetlana Slapšak considers it among the best, and possibly the best Yugoslav film ever made. Hana and Judita wear: short-sleeved bodysuits from the costume designer’s archive Slaven wears: swimsuit bottoms from the costume designer’s archive

Andrija: I took a short break before watching it. I’ve noticed that it usually happens that the films I work on come out two or three years after we’ve shot them. First, I want to rest from the project, then I start missing it, but I can’t watch it yet because color correction, music, or something else isn’t finished. You distance yourself a bit, which is great — it’s all part of the process. That’s how it was this summer when I finally returned to Yugo Florida after a long time, and it definitely marked my year. I think we’re missing films like that. Above all because of Vlada, who’s phenomenal. He was very careful not to let us slip anywhere. That’s true dedication. He went through a personal struggle here, with himself, since the story is about him and his family, and in that sense he helped himself through it. He was in the house where the story takes place. Not everything is identical, but that’s the essence. I think Vlada Tagić is an incredibly important figure — both for the scene and for our acting lives.

Teodora: It seems like that sense of recognition between people, that feeling you get, is an important factor when choosing which projects to work on, in any artistic field really. Is that true for you? Does it help you when choosing roles? How do you decide?

Andrija: I’m generally not afraid of work, and I don’t look down on any job. Sometimes I deliberately challenge myself by taking on something that would make others ask why I’m doing it, just to see if a “bad” role choice can actually lead you somewhere unexpected. I think it’s worth doing that sometimes. So, when it comes to choosing roles, I’m not afraid of work, but I do know how to recognize something good. I think my gut has always told me what I should or shouldn’t do. With Yugo Florida, for instance, I immediately knew what it would be like. Same with Morning Will Change Everything — you just feel it after the first table read. If we can recognize that animal instinct in ourselves and channel it into something meaningful, that’s a privilege. And of course, the team is crucial, often decisive.

Jovana: For me, the atmosphere on set is extremely important — that’s what we were saying about Tagić and Morning. There really is a sense of connection among people. I just remembered, we all worked together on Suspicious Characters, Nušić’s play adapted as a sitcom. It wasn’t widely covered, but it was great for us. So yes, I focus on the team. If there isn’t a strong team, I rely mostly on intuition. I try to stay rational and practical, but feeling always prevails. Sometimes something is technically impossible — then it’s an easy decision. But for everything else, I usually know right after reading if it’s for me. I’m lucky to be able to choose, because in this profession, especially when you’re young, that’s not easy. I was fortunate to start working early, and now I have a certain continuity. And when you have that, you gain confidence, and it’s easier to say yes or no.

Andrija: It’s not easy, but honestly, ever since I was born, nothing here has been easy (laughs). I remember when I started working, Montevideo was the only project being filmed at that time. Even then, opportunities were scarce, people were wondering if anything would be produced at all. The same names kept circulating — maybe someone could say that about me now too (laughs) — but it’s always hard when you’re starting out. Only now it’s become even worse on a larger scale. Everything has turned absurd. Theaters are closing, there’s no open call for film funding next year. That’s not normal. What will people watch? What exhibitions will they go to?

Jovana: True, and it’s probably not easy for young chemists or painters either, but when you’re an actor, there’s even less room for stable engagement and security. But still, that’s not necessarily what everyone strives for. Some people prefer freedom. Oh, but do you remember when there was a period when dozens of soap operas were being shot? I don’t have anything against that, but that kind of fast, assembly-line work can be frustrating and doesn’t contribute much to artistic growth. In any case, now everything has been cut short, like you said — many budgets have been reduced. I just hope something new will emerge from it, a response similar to the Black Wave we’ve been recreating. A new wave of bold steps, where young directors — or these students who’ve already shown how brave and talented they are, both in their art and in these protests — will offer a fresh perspective.

Teodora: That necessity for engagement is exactly what brought me back to the Black Wave at this moment. Do you think that kind of artistic courage is still possible today? Can film still be a tool of resistance?

Andrija: Of course, it brought you back because we’re literally in a black wave right now. I don’t know, it feels very difficult. Everything has to go through too many hands. If you make a socially or politically charged film today — one that might make more than fifteen people stop and think — it might not even get released. Look how long The Sabre and Black Wedding had to wait. Until we resolve certain other issues, it will be very hard. The only real space left for change is the street.

Jovana: What I love most about the Black Wave is exactly that courage — artistic courage. Technically, they were shooting on film. It was extremely expensive, and they had very little time. Today, we’re equipped to shoot almost anything with a phone, yet they were the ones who were so bold and authentic. That realism, bordering on documentary, is something I don’t think we’ve achieved yet. I’m not saying it has to happen the same way again, but that’s what makes it special. I love those films deeply, and I’m always surprised by how contemporary and ahead of their time they still feel.

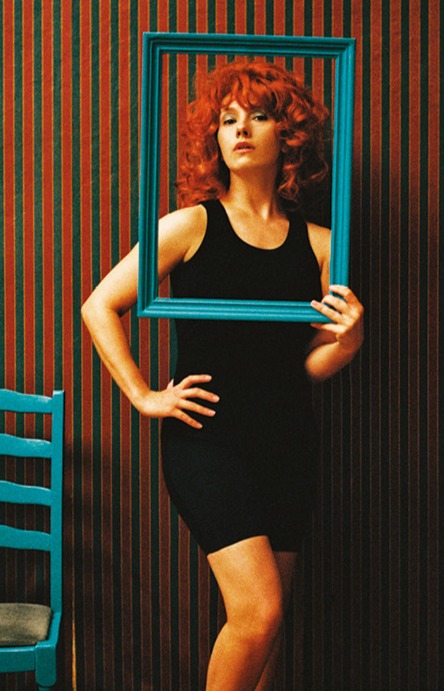

Man Is Not a Bird (1965, Dušan Makavejev) Dušan Makavejev’s first feature film follows a love affair between an older machine specialist and a young hairdresser, exploring the subtle and not-so-subtle challenges that come with their relationship. Upon its release, a critic from The New York Times described it as “the most original, intelligent, witty, and significant film he had seen that year.” Silk lace midi dress, Angelica Montini

Andrija: Yeah, but I think artistic freedom today is practically nonexistent, and in a way, it’s our fault because we accepted the compromise. Take a simple example — look at commercials. Do you remember that Vojvođanska Bank ad with Koja, Bjela, and Manda? It’s a horror show. If you aired that today, they’d sue the actors, the bank, and the TV station. We’re slowly being boxed in, and we agreed to it step by step. Every shot is over-edited, every scene has seventy-two cuts — we’re dumbing down both ourselves and the audience. I watch Živko Nikolić’s The Beauty of Vice, one take, and you understand everything in three scenes within a single shot. For me, he’s Almodóvar before Almodóvar. Everything’s getting duller now, even Hollywood has collapsed. I’m glad you mentioned film stock because I really think digital cameras have taken something away. Everything is made to look like you’re there, but I’m not there, and I’m not crazy enough to think I am. I’m watching a film — that’s the beauty of it. I don’t like HD or shooting on memory cards, even though I never worked on film myself. I don’t even like when films are remastered. I know the mistakes in a film and I love them; those flaws are part of creation. Everyone in my neighborhood used to joke about the scene where Irfan Mensur says to Gaga Nikolić in Floyd: “And take care of yourself…” They’ve now cut that whole bit because he didn’t actually say anything. Everything smells like alcohol, like antiseptic — it’s all sanitized.

Jovana: Yes, and that really hurts because, if we look back at the Black Wave, for artists it was natural to critique the current moment. That was simply expected. But today, that kind of attitude instantly gets labeled as negativity. I thought it would stop at words, but it’s clearly become much worse, and I don’t know how far this censorship and restriction of freedom will go.

Andrija: Freedom is shrinking in every sense. From censorship to the fact that we’re living in a real-life Big Brother world — it’s terrifying. I lost my phone recently, and honestly, for the first ten minutes I wasn’t sure if I’d rather find it or not.

Teodora: I agree, it’s not a bright picture. Not here, and not globally. The world is burning, and you’d think cinema would feel that — but it’s not really addressing it yet. Have you watched anything recently that moved you?

Andrija: Poor Things. That really stood out to me. Mark Ruffalo was brilliant. It’s a difficult genre because it’s neither fully comedy nor drama — it’s both. A wonderful film. The aesthetics, the color shifts, the framing, amazing. Oh, and last year That’s All for Today. I saw it four times in the cinema. It reminded me of a simpler time, without phones, when we didn’t know if we’d have money on Monday. Many of us were disappointed, but we were together. The pillowcases didn’t match, but there was a place to sleep. It brought that back. If our industry were functioning normally, that film would be filling theaters. It’s the kind of film that teaches people to love the cinema again.

Jovana: I recently saw One Battle After Another. I told you about it on set — it really struck me, I loved it. A true genre film, brilliantly directed. The soundtrack with the drums that never stop — incredible. Also Adolescence — bold, a step forward. But in general, I have to agree with what Andrija said. A lot of what I see feels lukewarm. There’s a visible lack of courage.

Teodora: What is it, then, that keeps you from giving up acting despite everything?

Jovana: Magic. I expect a lot from myself and from others. I’m not insanely self-critical, but I have a clear idea of what needs to happen, and when the result falls short, it hits me hard. That’s normal though — you can’t get everything you envisioned on set. But sometimes something happens that’s even greater than what you imagined. A kind of magic appears, and that’s what keeps me going. I ride those waves and could work a hundred hours straight. And the people — I love being on set surrounded by familiar faces. We’re a bit crazy sometimes. You don’t think about what’s best for you; you just follow what drives you inside.

Andrija: What drives me is play. I really love my job, and the moment I stop loving it, I’ll quit — I’m sure of that. So it’s play, surprise, discovering new parts of myself through new characters — but it’s all still me. I play with my work, and I love that. I tease it. I remember an older colleague told me about ten years ago: “You’re great, but step out of your comfort zone.” I thought a lot about that, and he was right. I like listening to both younger and older colleagues; I know what’s worth taking in. If you don’t ask questions, you can’t grow, and once you stop growing, you’re dead. When you start believing you know everything and no one’s opinion matters anymore, you’re artistically dead — they just haven’t told you yet.

Fashion Editor: Taylor Angino

Talent: Hana Selimović, Jovana Stojiljković, Judita Franković Brdar, Slaven Došlo, Andrija Kuzmanović, Matej Zemljič

Costume: Suna Kažić

Makeup: Irena Miletić

Hair: Milena Maršić

Set Design: Sandra Subić

Set Decoration: Vitomir Kovačević

Production: Teona Milićević, Marita Bobelj

Photography Assistant: Darko Sretić

Costume and Fashion Assistant: Anastasija Jovanović

Makeup Assistant: Nemanja Radočaj

Lighting: Etar Film

Special thanks to the restaurant

Tri Šešira, Maša, Steva i Stela, as well as Milošević Sheep Farm

Cover photo: Mysteries of the Organism (1971, Dušan Makavejev) Jovana wears a sleeveless top by Coperni and shorts from the costume designer’s archive.