Vogue Adria editors reveal which books changed their perspective in 2025

December 24, 2025

There are books we expect to amaze us, and they do not disappoint. And those that make time stop for a moment and allow us to temporarily forget everything that worries us. And those that answer exactly what worries us and heal us in an entirely new way. And those we do not like at first, but return to years later, when they become precisely what we need. And those we would not normally choose, but they choose us. In short, there are books. And that is probably one of the better things humanity has managed to create. This year was difficult on many levels and in many ways. But it was precisely these small refuges that helped many people make sense of situations, pause them temporarily, and simply change perspective, and the editors and journalists of the Vogue Adria team share the titles that marked their 2025 and by which they will remember it.

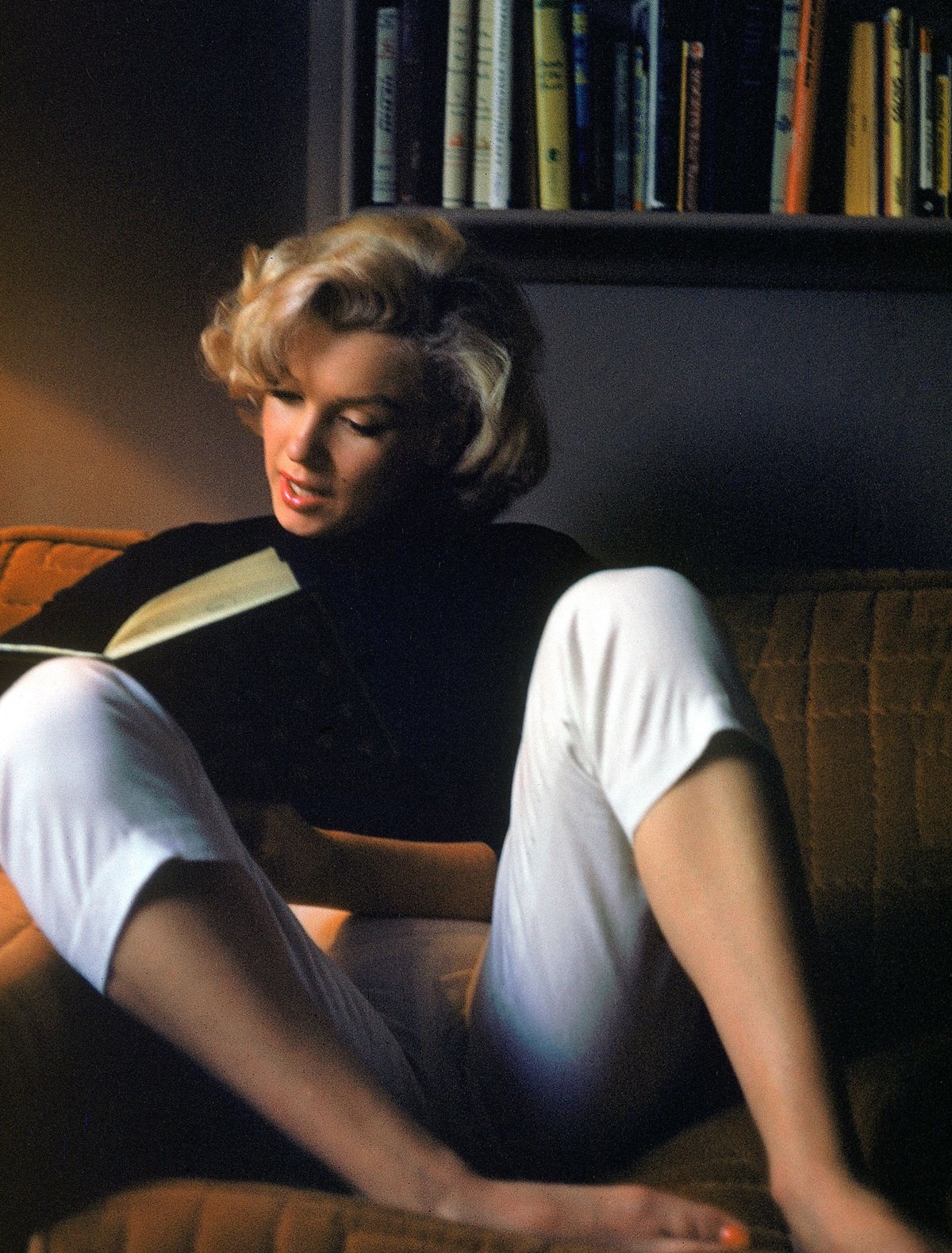

This year pushed me to my absolute limits in every possible sense. Not always in a bad way, though most often in a strange one. It was the year in which I traveled the most, met the most people, enjoyed myself the most, but also cried the most and felt the first charms of the beginning of my Saturn return, which they say will hit even harder in 2026. A year like that meant only one thing, that I read more than ever. Someone once told me that somewhere around the age of twenty eight the world suddenly accelerates and becomes incredibly tangled, and that it never truly returns to what it was before, and in that realization the book “Sve dobre barbike” by Katarina Mitrović came to me like a manual. Although it was published in 2024 and I saw the stage adaptation at the end of that same year, it arrived at exactly the right moment as ideal reading for the start of a year when I felt the most lost, helpless, and as if I were staring directly into an abyss whose bottom I could not see. “Sve dobre barbike” managed to remind me of some older, in fact much worse times when I was almost in the same position as the protagonist, and that those are no longer these times, that many things have been resolved, and that a world that is falling apart will probably never stop falling apart, and that I have to learn to live with that internalized global pain.

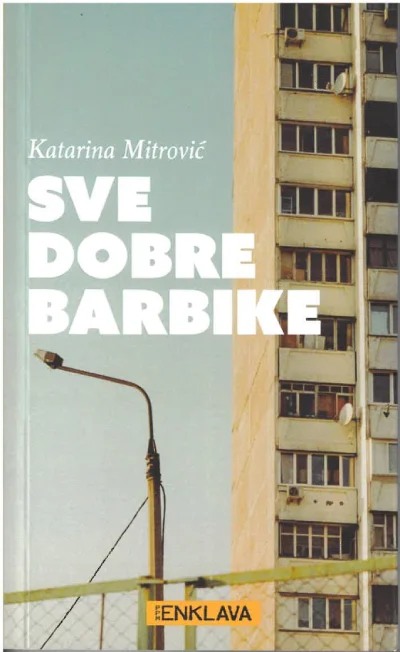

Along those lines, I returned to the book “What About Activism?” edited by Steven Henry Madoff in 2019, which I believe is more relevant this year than ever. Madoff brought together authors from different fields, and in their essays they all deal with one question that sounds simple but in reality constantly fractures: what can art actually do today. Not what it should do, not what we are used to expecting, but what it realistically can still do. When the book was published in 2019, it felt like a theoretical tool for understanding the contemporary art scene which, at least nominally, was trying to respond to political upheavals. Today, several years later, it reads entirely differently. As if in the meantime we have lost faith in the power of collective gestures. Not because of a lack of desire, but because of exhaustion, cynicism, and a constant abyss that devours every possible message before it reaches an audience. In that sense, the book is unexpectedly contemporary. It emphasizes a paradox: activist art exists, but at the same time it feels as though its space is narrowing, as if its signals are being diluted. This is especially visible in Serbia and the region. Art here has long been doing double duty, trying to survive in a system that offers it almost no institutional security, while at the same time carrying the expectation to be politically sharp, brave, critical. It seems as though activism in art has become self harm rather than a genuine act of change.

Both books felt to me this year like two sides of the same coin, “Sve dobre barbike” took me back to my own ruins, and “What About Activism?” to the social ones. In that connection I realized that 2025, through its rearview mirror, showed me a small preview of a future with millions of possible outcomes, and you know yourself that objects in the mirror are closer than they appear.

I firmly believe that books find us at the moment we need them most, which is why I rarely read novels as soon as they appear in bookstores. That is why I will remember 2025 by two novels that were published in 2024, but which at the time I would not have had the strength to enjoy, because of their complex themes that also affected me personally. I bought both books while traveling, without knowing what they were about, simply intrigued by their titles and by words of praise from some of my favorite authors. I had no idea they would help me understand my feelings more than a whole series of books on personal development and mental health that I have accumulated on my shelves over the years.

“Blue Sisters” by Coco Mellors and “Intermezzo” by the much loved Sally Rooney are novels about the loss of a family member. But more than that, they are novels about family relationships and the love we sometimes express in unusual ways. Through the skillful intertwining of multiple perspectives of characters consumed by grief, both books, though fundamentally different, dissect the process of mourning a loved one and show how it affects everyone differently.

At times it is easy to think that a character is very unlikable, almost amoral, but then you remember that all of their actions are simply a reflection of inner turmoil driven by the greatest pain, and everything starts to make sense. This is also thanks to the authors’ narrative skill, as they have managed to create worlds so real that you can almost smell the rooms in which the characters conduct emotional conversations or recall warm moments. In some characters’ actions I saw a reflection of myself, and it is extremely unusual to observe your own traits from a third perspective, while in others I saw members of my family. As if these two novels were little packages containing every emotion, anger, suffering, pain, but also the all encompassing love we perhaps feel most strongly in moments of tragedy, they helped me approach my own feelings, and the feelings of my loved ones, with greater empathy. And is that not the point of great literature?

What delighted me the most, however, is that although they are fundamentally sad, both books actually gave me hope. They flawlessly portrayed sibling relationships, from terrifying fights that prove we always hurt those closest to us most easily, to endless support that persists even within that anger. They served as a touching reminder of the strength and beauty of sibling love, which, at least so far, has pulled me out of the darkest emotional depths every single time.

I spent this year breaking down my own anger, over wars, violence, illness, political and social injustices, inequality, institutional failures, the denial of rights, personal inner conflicts, feel free to add your own source of frustration to this list. But it was not suppressed anger, on the contrary, it was marching, parading, deafening anger. As if every unspoken truth could kill me, I fired shot after shot, thunderous and shrill, and each time that move chipped away at a part of me as well, almost inadvertently. When I met Jennifer Cox, the author of the book “Women are angry”, which was named self care book of the year in 2024 and translated into Serbian in 2025 by Laguna, I did not ask her only why that is the case and how to deal with it, but also how to avoid losing ourselves in that constant, overwhelming anger. She told me that in this case she quotes Dawn Laguens: we do not stop fighting, but in a world that is almost falling apart from hatred, let us do so with love. The book is based on case studies, anonymous confessions of patients Jennifer treated, divided by life stages, from childhood to old age. It brings together all those experiences that can cause anger throughout our lives, from unresolved feelings around abortion and loss, exhausting motherhood, feeling undervalued at work, a partner who does not contribute, to sexual harassment.

The key claim is that our anger is justified, but if it is not channeled, we can become extremely destructive, both toward others and toward ourselves. All of this is the cause of the largest number of illnesses in women, migraines, anxiety, depression, autoimmune conditions, and even the most severe diseases. In her book, Jennifer proposes a variety of physical strategies for releasing emotions, which I combined with mental ones learned in psychotherapy, about emotional regulation, a crucial skill of control that, unfortunately, in these parts we have not practiced enough in childhood. The goal is not to stop feeling anger, but to transform it into something that can benefit us and help us regain control. I have not stopped fighting, but in a world that is almost falling apart from hatred, I do so with love.

In the meantime, I also recommend a manual in the form of timeless poetry such as “Lirika Itake” by Crnjanski, that revolutionary manifesto of protest, dignity, and freedom of personal thought, with all the irony, sarcasm, and grotesque whose meanings are still clearly readable a full century later.

“We no longer believe in it,

nor do we respect anything in the world.

We expect nothing with longing,

we mourn nothing.

We are fine.”

Our elegy, M. C.

Rarely have I had such a poor opinion of a year as I do of the one that is coming to an end. I spent it stuck between incomprehension at a world in which everything that is happening is possible, disappointment that despite repetitive lessons we clearly learn very little, bursts of enthusiasm that at least here something might change, and pride in young and brave people whom I claim are currently the greatest European fighters for democracy, followed by absolute defeatism that everything will remain the same forever, personal emotional breakdowns, wrong decisions, the right people, obsessions with black holes, hours of therapy sessions during which I extensively explained all of the above and how everything is connected by cause and effect. In short, this year I feel more grown up than usual, which I am not sure how much I like, but and this is a very big but adulthood makes us change and finally start living some lessons we repeat over and over again. Saying “no” is not as simple as it sounds, and it so happened that I learned that this year just around the time Sara Ahmed, the feminist theorist and researcher, published the book “No Is Not a Lonely Utterance”. It is an excellent essay on how women, and other marginalized people, learn to say “no”, and on the political, emotional, and social weight of that “no” in a world that constantly suppresses it. “Behind many catastrophes are unheard complaints” is a painful sentence that resonates on every level of society. On the other hand, I spent this entire year returning to pages that once repelled me during my studies, namely the Middle Ages. As I said, I am changing. There are many reasons why I think the Middle Ages are closer to us than ever, and I spent a good part of the year looking at them from a different perspective, trying to understand everything that is usually not part of the narrative when we talk about them.

Since the “ugly” has always fascinated me more than the beautiful, I often returned to “The Ugly Renaissance: Sex, Greed, Violence and Depravity in an Age of Beauty”, a book that is a kind of marathon through the dirty, raw reality behind some of the most famous works of art and cultural innovations. I was unusually fascinated by female saints, so I turned to “Femina” by Janina Ramirez, a feminist reinterpretation of the Middle Ages that shows women were not passive, invisible, or confined to homes, but active, politically significant, economically present, and culturally influential, and at times I ventured even further into antiquity with Svetlana Slapšak and her cult book “Antička miturgija: žene”. This year threw me in many directions, and books threw me in many directions as well, but in the end, everything fits into one word,

Those who know me will probably laugh out loud at my choice, but the book I had to reread is “Factfulness” by Hans Rosling, which I have been recommending to everyone for years. Few things fill me with optimism like the concise and clear explanations of this Swedish doctor and statistician that the world, despite all its flaws, is much better than we think. When, however, we allow bad news to take on gigantic proportions instead of looking at a fact based picture of the world, we lose focus on what truly represents the greatest threat. Given everything that is happening in the world today, I needed a dose of positive energy, and I know I can always find it in this book.

What is interesting is that when someone asks us simple questions about the state of the world, such as what percentage of the global population lives in poverty, why the number of people on the planet is growing, or how many girls finish primary school, we systematically choose the wrong answers. That is precisely why Dr. Hans Rosling in “Factfulness” offers a new, radical explanation for why this happens and exposes ten instincts that distort our perception, from the tendency to divide the world into two categories, most often “us” and “them”, through the way we consume media content that fuels fear, to how we perceive progress, believing that most things are actually getting worse. Our problem is that we are not aware of our own ignorance and that the prejudices we carry deeply within ourselves influence even our guesses. It is something we need to remind ourselves of from time to time, because everyday life can be so dark that it is truly difficult to notice even the smallest glimmer of light.

.

Those who know me will probably laugh out loud at my choice, but the book I had to reread is “Factfulness” by Hans Rosling, which I have been recommending to everyone for years. Few things fill me with optimism like the concise and clear explanations of this Swedish doctor and statistician that the world, despite all its flaws, is much better than we think. When, however, we allow bad news to take on gigantic proportions instead of looking at a fact based picture of the world, we lose focus on what truly represents the greatest threat. Given everything that is happening in the world today, I needed a dose of positive energy, and I know I can always find it in this book.

What is interesting is that when someone asks us simple questions about the state of the world, such as what percentage of the global population lives in poverty, why the number of people on the planet is growing, or how many girls finish primary school, we systematically choose the wrong answers. That is precisely why Dr. Hans Rosling in “Factfulness” offers a new, radical explanation for why this happens and exposes ten instincts that distort our perception, from the tendency to divide the world into two categories, most often “us” and “them”, through the way we consume media content that fuels fear, to how we perceive progress, believing that most things are actually getting worse. Our problem is that we are not aware of our own ignorance and that the prejudices we carry deeply within ourselves influence even our guesses. It is something we need to remind ourselves of from time to time, because everyday life can be so dark that it is truly difficult to notice even the smallest glimmer of light.

The first photograph by Sebastião Salgado that I saw, about ten years ago, I remember, depicted a chaotic crowd of people. Seen from above, they resembled a human chain of slavery, an uncontrolled mass without a helmsman, but with the hope that work in the then accidentally discovered, and today completely exhausted, Brazilian gold mine Serra Pelada would lead them to a better life. Later, I watched Wim Wenders’s documentary film “The Salt of the Earth”, and only then did the full magnitude of one of the greatest protagonists of contemporary documentary photography become completely clear to me.

In the year when Salgado left us, the Italian publisher Silvana Editoriale, specialized in art editions, published in November the monograph “Sebastião Salgado”, edited by Pascal Hoël. The book presents two different phases of his oeuvre through a selection of more than 400 prints from the collection of the Paris museum Maison Européenne de la Photographie. The first part takes us through the first twenty five years of Salgado’s career as a photographer and photojournalist, during which he constantly confronted the anger and suffering of humanity through famous series such as “Workers” (1993) and “Migrations” (2000). This is followed by a selection of works from the project “Genesis” (2013), an epic eight year journey aimed at photographing mountains, deserts, and oceans, as well as animals and communities that have still managed to escape the influence of modern civilization. These later works are an homage to the beauty and fragility of our planet, still untouched by human recklessness, whose preservation is of crucial importance.

Sebastião Salgado was a quiet observer of the world, a visual poet who turned even crowds of suffering people into scenes reminiscent of myth. Above all, he was a humanist who placed human issues and the upheavals of the world at the center of his projects. In a time marked by bleak everyday reality, wars that, despite centuries of lessons, continue to persist, and political vortices that serve only a privileged minority, the rich legacy of this Brazilian master of photography remains with us as a powerful poetic diary, a testimony of where we have been and how far we have come, but perhaps also a small incentive to act toward a better tomorrow, starting at least from our own micro universe.

At a time when AI seductively offers shortcuts and in doing so erases all the capriciousness and unpredictability of creativity, reducing the written word to a soulless sequence of verbs and nouns adorned with unnecessary epithets, I return to the book I call the “Bible of creative creation”. The book “The Creative Act” by Rick Rubin, an American music producer with nine Grammy Awards, is a book I received as a gift from a friend a few years ago and have not put down since.

“The Creative Act” sees creativity as something sacred, something that should not be rushed, something that has its own flow, something that does not have to be “perfect” to have value. Rubin’s words are comfort and encouragement for all those who falter before the “robotization” of creativity, or are worried by it, and think they cannot fight it. What particularly moved and encouraged me in “The Creative Act” is the spiritual note of creativity that Rubin unpacks so meaningfully that the only conclusion that imposes itself is that creativity is, in fact, simply existence: an invitation to make mistakes, to experiment, to change our minds, to seek answers, to be patient, to listen. He teaches us that creativity is born from the beauty of life, from awareness and wonder. That creativity means seeing the world beyond the everyday and the ordinary. That it is a process, not a shortcut offering instant, worthless solutions.

“A wrong turn allows you to see landscapes you would otherwise never see.” And that is precisely where all the beauty lies. A wonderful reminder that creativity must be nurtured because it is far more than the final result, it is a way of being.

As someone who writes for a living, I often reach for books that have nothing to do with my usual interests, which in my case is mostly the cosmetics industry, because I always strive to enrich my vocabulary and improve my writing skills. Watching films has long been “ruined” for me, because I much more often get stuck on beautiful sentence constructions and metaphors than follow the actual plot of the film. Still, from time to time books enter my life unexpectedly, whose point reaches me more strongly than the need for analysis.

After one rainy afternoon wandering through the Kunsthaus museum in Zurich, I headed toward the museum shop. Outside it was still pouring rain, so I had little motivation to leave the building. The museum shop was classically filled with various trinkets, interesting vases, spikes with unusual inscriptions, and heavy books whose primary purpose was to look good on a shelf rather than to be read. Yet in that colorful chaos, my eye caught a simple and very thin booklet with a direct title, “Calm, The Harmony and Serenity We Crave – The School of Life”.

It is a book of barely a hundred pages. Concise and clear. Beautiful and precisely written, but with purpose. It addresses almost every layer of human life in which we can experience unbearable nervousness and lose our temper, from interpersonal relationships with parents, family members, friends, or partners, to waiting for documents in the hell of bureaucracy or workplace conflicts that are inevitable. It analyzes sources of nervousness, compares similar situations in which one will trigger a nervous breakdown while another will be just a small obstacle in the day, and offers sources of harmony.

How do we achieve calm even when a situation objectively does not call for it? That is the point of the book. You will not become a Zen master after one reading, but I notice that I often return to it and read the same chapters with “new eyes”, and each time it gives me a new perspective. Even if the content does not immediately offer the answer I am looking for, the very act of reading such a humanly written book helps bring calm. Because the booklet is small, I often take it with me on trips, because I would rather direct my focus to it than to a feed, which very easily introduces nervousness into my nervous system.