Even though I somehow arrived at Le Petit Café ten minutes early, I wasn’t any calmer—or more focused. The chaos in my head spilled over onto the notes spread out before me. Had I written everything down? Did I forget something? What could I possibly ask that hadn’t already been asked a hundred times? It was a gray, damp Saturday morning, occasionally brightened by an autumn leaf caught in the wind. The atmosphere inside the café felt unusually hushed, its sepia tones blending perfectly with the muted chatter of the crowd. And then he entered: a gentleman in a timeless coat, a sharp gaze glinting behind his glasses, taking in everything. There was something about him that seemed out of time, as if he carried a thousand lives within him. I waved; he approached with an elegant stride and shook my hand warmly. He apologized for being late—though he wasn’t—and immediately suggested we use first names. There was both respect and a rare gentleness in his voice, as if we’d known each other for years. “I’ve been on the phone all morning,” he said. His schedule is packed—he’s working on several projects at once, in different places—but that suits him. “It’s a busy season, but they’re very good projects. I’m in a real working mood. I feel like it.” Naturally, I wanted to know what he was working on.

He took a breath and began to list them. “Just a few days ago I delivered designs for a classical ballet. I mostly do ballets with Valentina Turcu,” his expression softened. “Above all, and this is what matters most to me, Valentina is an exceptional, wonderful person. She’s a choreographer specializing in dramatic ballets; right now we’re working with SNG Maribor Ballet on a co-production with the Greek National Opera Ballet titled A Streetcar Named Desire.” He smiled broadly. “Then I’m doing a madcap comedy in a small theater in Koper. Katja Pegan is the director and a good friend from the 1980s. The play is Where Is the Prima Donna?, a screwball comedy set in the 1930s with a contemporary twist. We have everything here: costumes, colors, big scenes, and we’re having a great time. The premiere is January 23. At the same time, I’ve got A Flea in Her Ear on my desk for the Mladinsko Theatre in Ljubljana with Vito Taufer — another comedy.” His voice slowed. “I actually started with Vito. After Dragan Živadinov, Vito was the first to invite me, back in ’86, to do a mask. I started in theater doing makeup when I was still a kid. Then they realized that kid was actually making costumes. So I’ve worked with Vito since ’87, and the best thing is growing up together. We know each other so well that we always genuinely enjoy it. I call us classmates.”

Next week he and Valentina Turcu are heading to the HNK Zagreb Ballet to deliver sketches for Othello. After the New Year he’ll start on a co-production of HNK Zagreb and HNK Varaždin with the Dubrovnik Summer Festival: Edward III. “A lot is happening. I’m working with great people, my directors — we know each other inside out. Classmates, like I said. They’re used to my process; we’ve collaborated for years and they know exactly when the dyslexic switches on and when ‘Alan’ returns,” he concluded, settling back in his chair.

“How do you approach projects?” I asked next. “Does your process change for theater, ballet, opera, film? There must be differences.”

“Of course,” he replied. “Take a straight play. First, it depends on who you’re working with. The director always has a vision, an aesthetic. If the director is the conductor of the symphony, I’m just one instrument in the orchestra, following along with the rest. With drama it depends on the genre, and within that on the director and the guidelines — how much the costume design will be ‘dosed.’ But communication is the most important thing, as in everything. I’m the kind of designer who always keeps the sketch open. I don’t cling blindly to the first idea, because communication with the actor, singer, dancer matters to me enormously. I’m always researching who this person is, this character in the drama, production, or choreography. I work hard to respect their vision, notes, and wishes.

“Opera costumes are usually done in the old school: you build a palette. In ballet, as in opera, you work within the frame — classical or contemporary. With Valentina we started in classical ballet with Anna Karenina, and later, in contemporary work, we stripped the design down to essentials.”

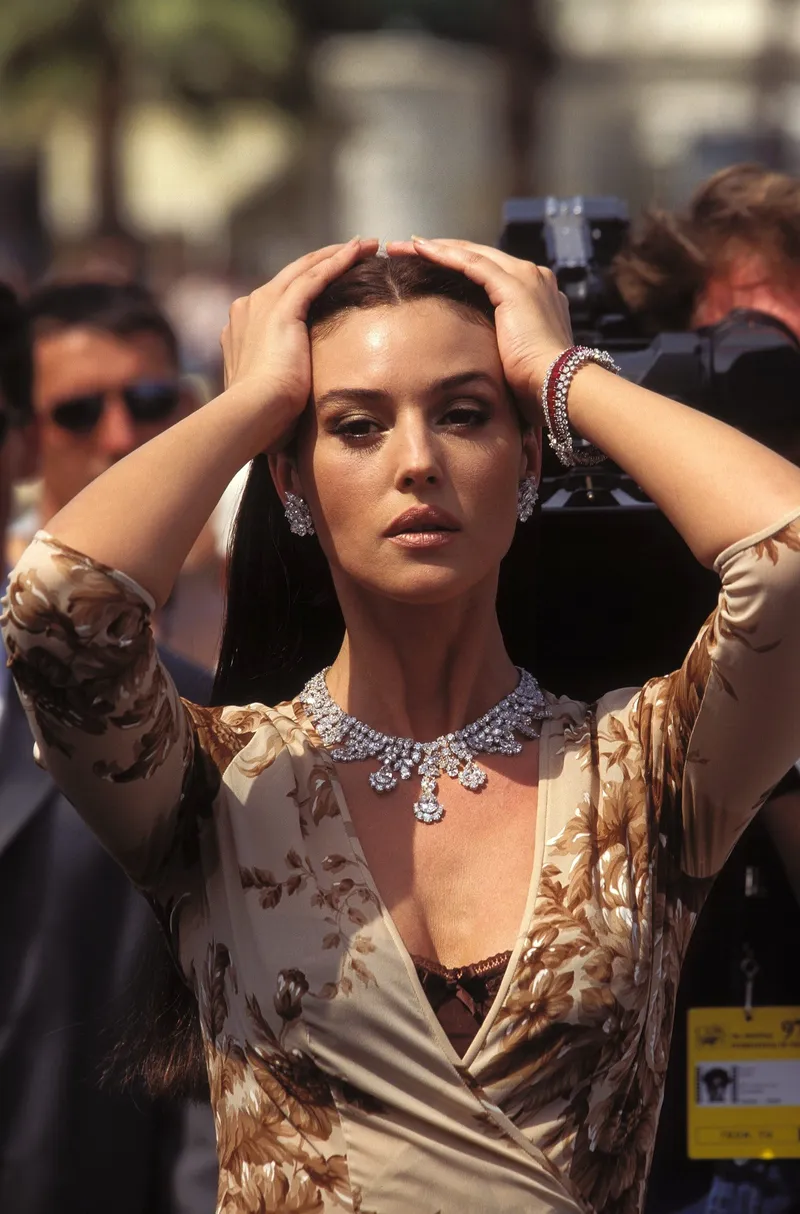

Photo: Borut Peterlin

He paused, shaping the next thought carefully. “You know how it is — there’s a process. It takes time and a certain number of projects for people to really get to know one another, for you to sometimes guide them. I call it growing up together in the creative process. With Valentina, for example, we listen to each other closely — it’s about trust.” After a moment of quiet he went on: “With film you have to reduce and minimize about fifty percent right from the start, because you’re working with a camera and everything is up close. And again, it depends on who you are as a designer — where your personal boundaries end and your creative ego begins. You need to keep yourself in check so you don’t cross those lines. That’s often the hardest part on big projects with lots of people, lots of egos, lots of ideas — you steer carefully through the middle.”

I tried to picture the arc from idea to sketch to final garment. “Do you prefer total freedom, or is it easier when you’re given parameters?”

“That’s the art of communication, alignment, and control. Many people in the creative process don’t understand the line between the personal and the creative ego. I’m never completely without limits — there are directors, a vision, a production. That’s how it is, and I’m fine with it. It suits me, because I can jump between different kinds of design, which is great for me — I’m constantly questioning myself. With some directors I’ve worked for twenty years, and we’ve reduced the costume design to the absolute minimum where it served the project. I pushed for that. The counterbalance between one approach and the other gives me creative equilibrium. I’m rarely one hundred percent free — only in exhibitions. None of it is better or worse. I need all of it.”

“About fifteen years ago,” he continued, “German costume design was dominant in theater — extremely minimalist. A kind of ‘non-aesthetic within the aesthetic,’ with lots of vintage elements and mixed influences. Some designers understand that language brilliantly — how much to weave their taste into the work so it isn’t heavy-handed or intrusive, but just right. There you see how much some of us work with actors within the design — peeling back layers to reach the essence of the character while honoring the performer. Costume design is, first of all, character dramaturgy, and therefore character psychology.”

He took a sip of green tea and spoke with warmth. “You also have to be a bit of a psychologist, to catch and read all those threads. My childhood helped me with that. I spent a lot of time with psychiatrists and psychologists as a kid. It shaped me and gave me personal and creative breadth. It helps me listen to people and understand them. Which is why communication matters to me so much — like now, between us. I approach every person and every project as if I were doing it for the first time.”

If his ease and kind openness surprised me at first, I now understood where they came from. Despite a remarkable career and a sea of experience, he approaches everything without assumptions or judgments.

Among his credits is designing for the legendary Cirque du Soleil, and I had to ask what that was like.

“Above all, it was a life experience. It’s a machine, a factory — they call themselves that. But the process is fundamentally the same: the director has a vision and we all follow it. A show there takes two years to build — one year to develop and create, another to put the costumes into production. Their workshops are, in my view, the best in the world, with around four thousand employees. Since you asked about creative freedom, I was probably the most constrained there of any job I’ve done. The process lasted two years.”

“Jean Paul Gaultier visited you then, didn’t he?” I remembered. “He did. Fridays were like open days for special guests, and they asked me to wait because a celebrity wanted to drop by — we didn’t know who. He arrived with his team, and in the end we chatted and laughed over bobi sticks and tea. He’s remarkably down-to-earth and very kind.”

Images crowded my mind: acrobatic corsets, fantastical creatures in the rooms of Ljubljana Castle, operatic crinolines… The next question asked itself. “Since you didn’t finish formal studies and are essentially self-taught, where do you draw inspiration?” He paused, and it felt as if the café’s bustle softened with him. He spoke slowly, translating each thought with care.

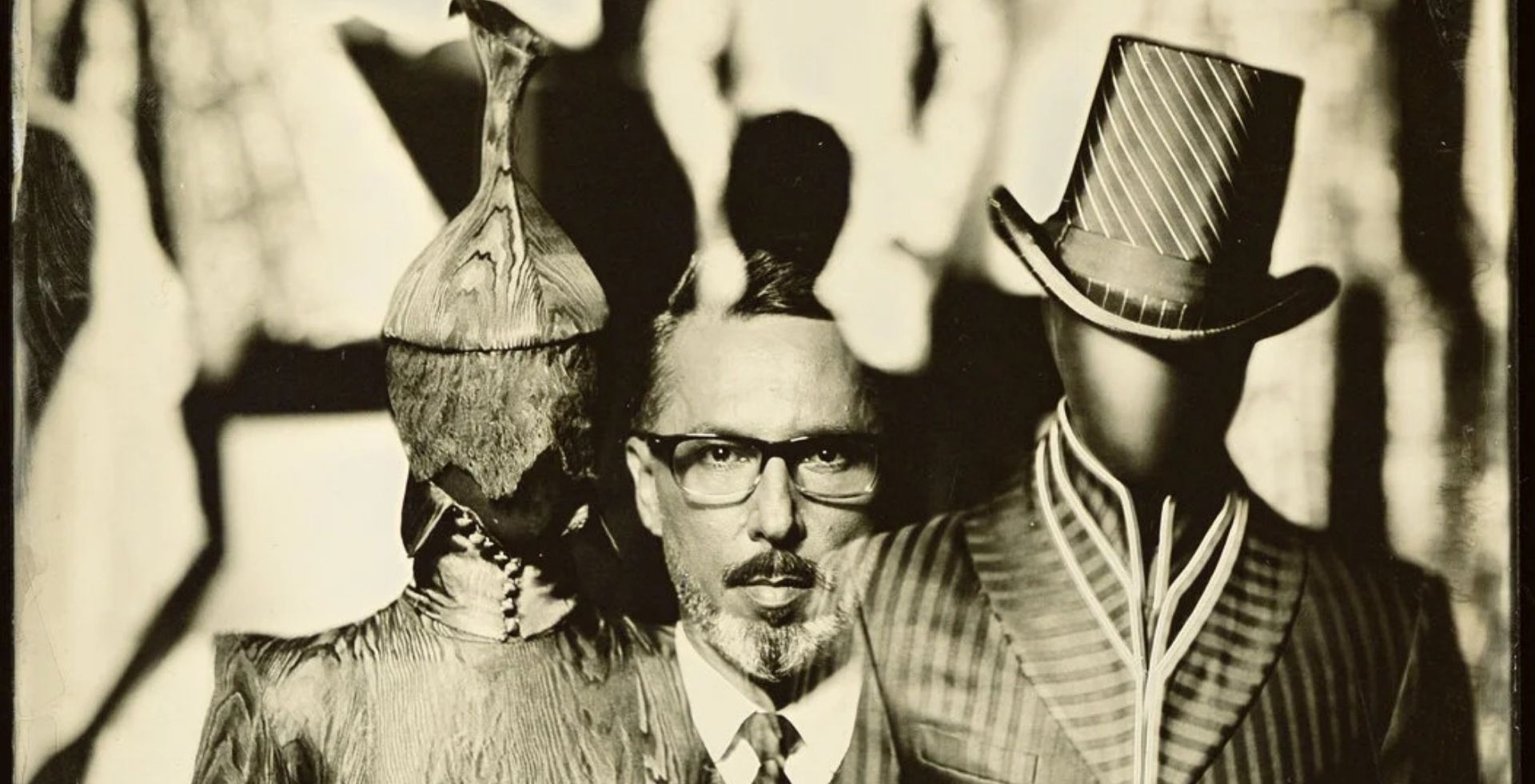

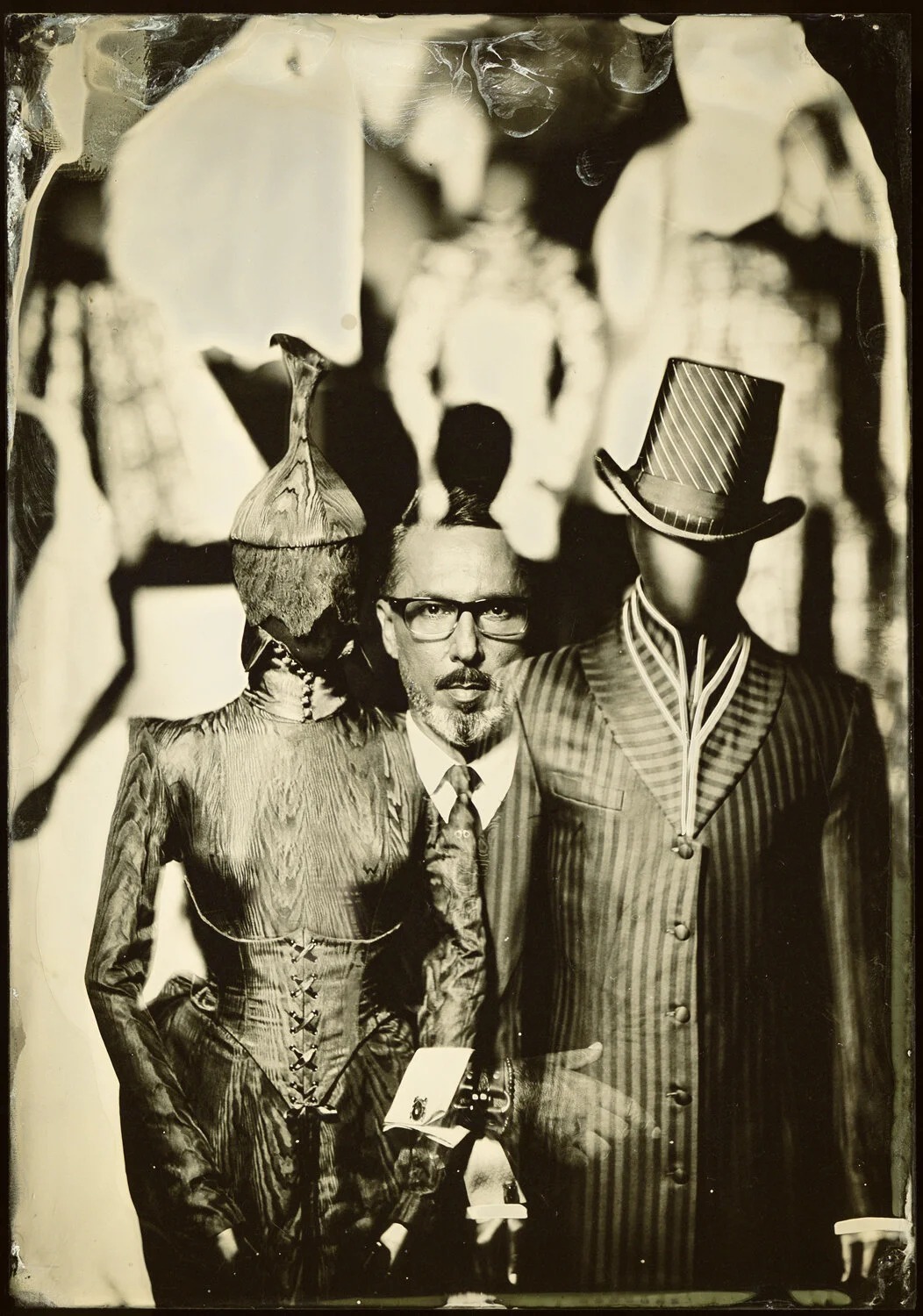

Photo: Iztok Umek

“It’s true, I didn’t learn this at school. The creative force has been inside me for as long as I’ve existed. Creativity heals me; it keeps me afloat mentally. My mother saw that when I was three. I didn’t fully understand what I was carrying in my subconscious that needed to surface, but I knew I needed help. In primary school I asked if I could see a psychologist. The school psychologist suggested we find a psychiatrist. That was in sixth grade, and years of therapy followed. Then I went to the School of Applied Arts in Zagreb and, thank God, they recognized that I’m a one-hundred-percent intuitive creative. We even agreed I could attend when I could. Both psychologists and teachers understood that my creativity kept me grounded enough to function through the day. I don’t know exactly where it comes from; I only know that when I create, I surrender completely. I’ve spent my whole life trying to protect it, because it’s sacred to me. It heals me, and it is my essence — what I breathe, live, am. I didn’t choose this path; it chose me. I just follow it. And I’m deeply grateful.”

I understood him completely — not so much consciously as on a sensitive, almost subconscious level. In that pleasant quiet, the thoughts seemed to mingle with the smell of coffee and hang above us.

“Are you superstitious?” slipped out of me. He smiled. “I don’t think of it as superstition. I believe in it and work with it every day. If I had to choose, I’d say I’m a Buddhist — an awareness of the self and the world. I’m aware that everything simply is — and all of that flows into my creativity. Astrology, the cosmos, invisible worlds… they’re part of my everyday life.” At this point, our conversation drifted into places I’ll keep between us. Not because Alan wouldn’t share — quite the opposite, he is disarmingly honest, especially with himself — but because those words were spoken with a higher purpose I’m still trying to understand, and I couldn’t do them justice on the page.

I should admit that none of this — except our conversation — happened quite as I’ve written it. We didn’t actually meet; we didn’t sip that coffee. This is how I imagine our interview would have looked if our schedules had allowed us to sit down in person. After we said goodbye on the phone, his words echoed with me for a long time. Not because they were grand, but because they were bare and sincere. They confirmed what I had sensed: true creativity doesn’t grow out of ambition, but out of inner peace, gratitude, and harmony. When he speaks about his work, he is really speaking about life — and if life is an art, then Alan Hranitelj tailors it into a masterpiece, every day.