When I met Adrijana Gvozdenović for the first time, it was the beginning of an experimental research project led by Kurziv/kulturpunkt.hr a bit more than a year ago. We got to know each other in a Zoom meeting, where we started discussing ‘anomalies’. We naturally got into conversations about being different versus being part of something, and how this sense of belonging can change within the art world. Neither did I know who Adrijana was, nor did I ever hear of her alter-ego Adrian Lister before that. But through these conversations, I understood that we share a suspicion towards self-proclaimed peculiarities as well as an urge to reflect on how to actually exchange knowledge without showing off.

Hearing about the exhibition in Podgorica made me curious about how she would use a solo show for her practice which avoids many of the categorizations of artistic practices, and which usually involves collaboration and collectivity. I cannot say that it came as a surprise that even this moment of presentation turned into something that activates the audience, provides space for learning, and – ultimately – also transgresses separations between traditional roles in the museum, curator and artist.

When meeting to talk about the exhibition in Podgorica, it was the first time since discussing ‘anomalies’ that we met online again, but also the first time that we only focused on Adrijana’s artistic practice. There was a lot to unpack, especially about the trajectory from her alter-ego Adrian Lister towards the idea of a so-called workers’ club, which turns the museum into a place for gatherings.

Maximilian Lehner: How did your workers’ club find its way into the Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro?

Adrijana Gvozdenović: There was an open call for the representation in Biennale for curators and artists together. So Nela approached me with the idea of applying together to it. Initially, there was my long-term work Who is Adrian Lister? at the core of the project.

Maximilian: Since you put the question already: Who is Adrian Lister?

Adrijana: When I moved to Belgium for my studies, I translated a text for my CV, and the automatic translation made “Adrian Lister” out of my name. So, I started to ask “Who is Adrian Lister?” and made short performances out of it for several years. After my studies, there was a break in using this persona, and I only began to work with Adrian Lister as a tool when I was asked to participate in exhibitions dealing with identity or national representation. That’s also how Nela and I met. She invited me in 2021 to present Adrian Lister in Montenegro, within an exhibition dealing with the post-Yugoslav intellectual cultural space. It was also at a time when I had to move from Belgium back to Montenegro, like going to exile in my own country, so it was an interesting moment for Adrian Lister.

Nele Gligorović: Our collaboration began within the exhibition Marginalia of the Common (Marginalije zajedničkog), or how to read ‘yugoslavism’ in contemporary artistic practices. The exhibition emerged as a gravitating program of a regional initiative on a common language and the survival of the Yugoslav cultural space, despite state systems, borders, territories, and other political dictates. By questioning issues of identity, language, migration, institutions, and labor in art, Adrijana’s research Who is Adrian Lister? was the ideal choice of a contemporary Yugoslav, a migrant, and a cultural worker in Belgium. Since then, we have been talking, sharing tools, experiences, materials, and knowledge…

Photo: Anja Marković

Adrijana: So, there is a little bit of a messy situation there, which is very nice. Between extending our roles as curator and artist, and somewhere halfway, we decided that this will be a co-authored exhibition. I’m still an artist and Nela is the curator, but this is not defined in the exhibition as expected.

Nela: Aligned in our working methods, we strive to dismantle the rigid, hierarchical structures of art institutions, where the artist is the guarantor of autonomy, and the curator serves as a butler or guardian of the art world. Institutionally determined roles keep all participants in the art system trapped within their ‘authorizations’ or positions, limiting exchange and the advancement of experiences in the field of collaborative work, art as a practice of collaboration.

Maximilian: So, you unfortunately didn’t get to show this in Venice for Biennale. How did the project then develop towards the presentation in this different context, and – where is Adrian Lister in this show?

Adrijana: Adrian is absent, he was already disappearing in this post-Yugoslav space that was created within Marginalia of the Common. Thinking about the presentation in Montenegro brought us more to the questions about work in art, conditions of making, and how we can use the exhibitions space as a place of gathering. There are still elements in the exhibition which come from the initial idea but more as catalyzers for practices and activities.

Maximilian: Why did it end up becoming a workers’ club? Sometimes I’m surprised by how easily the terms working class and worker are used. These concepts are often present in the discourse on post-socialism and what we consider critical artistic discourse, but it’s actually difficult to determine what they even mean today?

Nela: The worker’s club is envisaged as a gathering space, an alternative form of education, a place for dialogue and expansion of knowledge. It is an experimental space, set within the institution of the Museum of Contemporary Art, which is framed by current social relations. Schools, universities, libraries and museums must be centers of class struggle. We must question institutional knowledge, truth, programs and actions. Tools for a better understanding of oppressive strategies used by social structures have been deleted from the humanities curriculum. Class is a word that remains silent. As we are flooded with information that hinders a critical approach to knowledge, we lack the tools for organization, action and change. This is why we decided to use an exhibition space as a workers’ club, not only for workers in culture, but for all those who participate in today’s capitalist production. The workers club represents an attempt to define and control the conditions of work, productive and reproductive, material and immaterial, which is why the exhibition takes on a format of discussion, workshop, conversation, lecture, exercise in joint thinking and action.

Photo: Krsto Vulović

Adrijana: In my practice, I question the very status of art works. I am interested in how art works. So, this is also how I relate to the idea of a worker’s club. I imagine a space where we can work together and gather and do stuff with art.

Maximilian: There are several instances in global history where workers and artists joined forces in unions, but knowing that you work in exhibition set-up, too, adds another layer to it.

Adrijana: Yes, and this experience informed my thinking and influenced my practice. I find it very exciting to work around exhibition protocols, rituals, practices, and try to repeat and rehearse them – and figure out what else to do. Here, we wanted to think about the time and space of the exhibition, to extend it to other authors within the space of magazine, to organize a program with workshops and talks, try to create community moments.

Maximilian: But how does this work when you are not there?

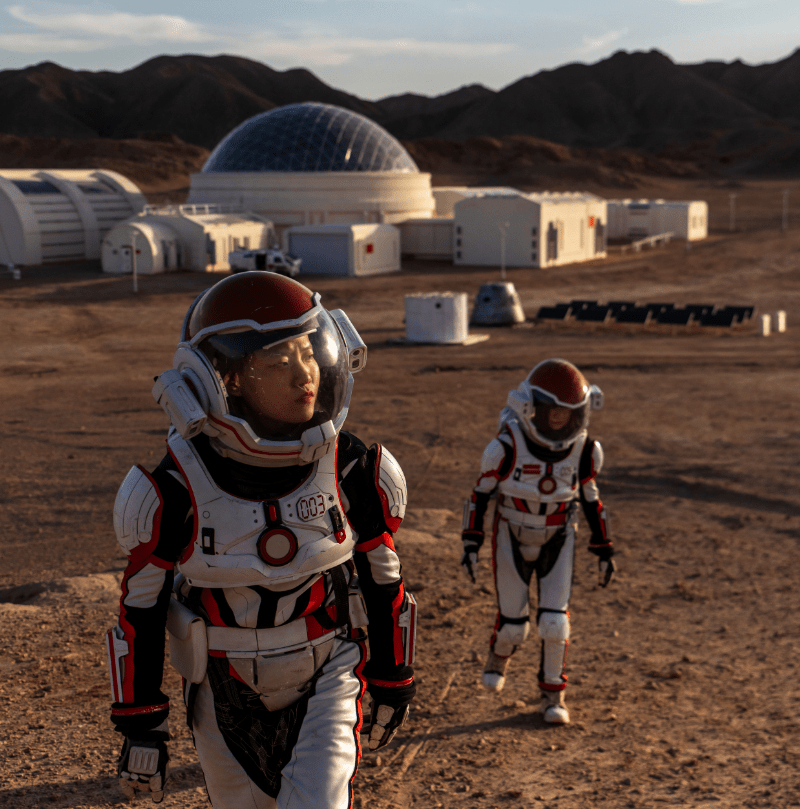

Adrijana:: We have some instructions. For example, there is this entrance situation where you can choose a role on how you will go through and approach the exhibition. They are briefly described and to each of them a piece of clothing is attached. Visionary, critic, comrade, time-traveler, diva, aesthete, cynic. These roles are supposed to help us form critical opinions, by moving between different perspectives.

Photo: Anja Marković

Maximilian: Did you think of people who might not be aware of all those roles? I don’t know about the local contemporary art audience, but I can imagine that some people in any context are overwhelmed by the choices and might not even know about those positions exist you know?

Adrijana:: We tried to make the texts very simple and descriptive. Originally, this idea comes from feedback strategies and even if the audience doesn’t engage to practice them, we will activate them during the discussions in workshops.

Maximilian: No matter which role you pick, after entering the exhibition, you immediately notice the remains of a torn down wall and the view to the outside.

Photo: Anja Marković

Adrijana: Despite its planned bureaucratic use, the architect of what is now the gallery building (Kana Radević) made the space very open to the outside, with large windows on both sides. For the purpose of using it as a gallery space, two big walls were added in front of the windows. We decided to tear down one of those walls, the one that looks at the garden between the buildings. It was done in a public event, accompanied by readings and exercises.

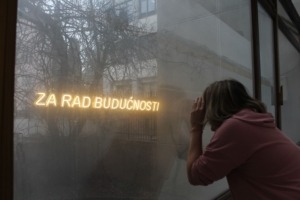

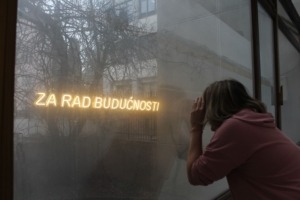

Nela: By removing the wall, we remove the barrier between the outside world and the interior of the gallery. With the idea to create space for communication with the community, and use direct engagement, horizontal knowledge and everyday resistance of the community, to generate locations containing a variety of knowledge, thus enabling availability and equality of that knowledge. In the garden, we installed a neon light writing. ZA RAD BUDUĆNOSTI (FOR THE WORK OF THE FUTURE, the last words taken from the Manifesto of the artist-worker Mirko Kujačić, created in 1932.

Adrijana: This is actually an idea for a work Nela brought into this exhibition, and one of the instances where the authorship started to blur. Also, when we destroyed the wall and leave its leftovers in the exhibition, we decided to show The Great Wall (Zlatni zid), a work I made in 2014/2015, next to it.

Maximilian: What do those have in common with the wall from the Montenegrin museum?

Photo: Anja Marković

Adrijana: It is a golden wall from the museum I worked in Belgium in as a technician and the last show I worked on featured some Renaissance paintings on a golden wall. When changing the walls, I took pieces with me, and I sanded them until a blue layer came to the front, as I remembered that underneath is a leftover of a Sol le Witt painting.

Maximilian: So, these wall pieces represent some sort of value through the work of the famous artist?

Nela: The Western art system – represented by the golden wall – is often upheld up as a model to which artists around the globe aspire, but this system comes with its own historical baggage rooted in colonialism, capitalism, and elitism. The decision to challenge this model in the exhibition also underlies that these ideals are not something to aspire to, but structures to be re-examined.

Adrijana: Yes, and even more. From the position of technician, I participate, with each show, in tearing down the walls and building them up again. The admired Western institutions are not working as efficiently and conscientiously as often perceived. I can’t stop thinking how the costs and labor invested in moving scenography between shows might as well be distributed to other kinds of practices.

Photo: Anja Marković

Nela: The diagram How Cultural Workers Live and What They Dream Of is an attempt to map the confusion within the existing structure of the art system. It appears as a tangled field of terms, seemingly precisely connected, yet leaving room for alternative directions. Class is positioned as the central issue of the art system, as understanding relationships in art requires understanding class relations that stem from economic inequality. Through the lens of class, it comments on the establishment of art history as a discipline that emerged in the 18th century within the framework and needs of the bourgeoisie. Furthermore, it examines how autonomy, as the dominant ideology of art, isolates art as a territory of talent and genius rather than a social subsystem defined by existing social relations. Burdened by the notion of the creative genius, the working conditions in art, the exhausted bodies of artists, and the invisible labor remain concealed.

Adrijana: Additionally, we edited the magazine as one of the works in the exhibition, with texts that give broader theoretical and experiential framework around art and labor. We also compiled a collection of all the texts we shared among us in preparing the exhibition, creating a library within a space.

Maximilian: You put them as copies there…

Adrijana: Yes, just as non-authorized copies. This is how we get access to most of the knowledge, no? It is also how we learned about art history in art school, through black and white photos.

Maximilian: It also draws attention to something in between reality and imagination, because when I think about some works, I saw back in art history classes on those black and white copies, I’ve had a totally wrong image of them.

Adrijana: It puts this idea of the necessity of the work existing, along with why does it even have to exist?

Maximilian: I mean, it’s such a different way of putting it if you have like the annotated references and the copies. It is also an image that you create, a working image that narrates that you are using these things and researching. That brings me also to the lack of pieces that would traditionally be referred to as artworks – like sculptures, paintings, or performances. Because even with what seems like that at first glance, you immediately pull out the authorship and state that it is found, made collaboratively, or it is attributed to the curator and co-creator of the exhibition.

Photo: Krsto Vulović

Adrijana: You know; what’s ‘the work’? I’m not sure, but I find it interesting and important to think about it. As for authorship, I like to think about it only through the responsibility. Also, I don’t think of being consistent or readable as an artist, but to add layers, to complicate existing notions, to allow complexity.

Maximilian: Then it becomes a trace like it’s self-contradictory, because, by avoiding originality it becomes like a like a hint to originality. It’s like: “Okay, I’m not doing any of this, that’s my thing.”

Adrijana: Perhaps, but that’s ok. Would be great if people find some time to spend in our workers club, if we manage to get some things done during the workshop, share references, open some discussions, have a bit of fun on the way – we would love to see that!

The exhibition is on view until 28th of february.