When times are hard, art is what makes life bearable. Not because it offers an escape from reality, but because it helps us face it. At least that’s how the American writer and activist James Baldwin understood it. And when systems have been unstable and unreliable for decades, when culture has gone underfunded for so long that we can now say it receives almost nothing, it inevitably becomes a marginal field that fights with all its strength to hold its place. In that fight, cultural institutions are crucial. In that sense, the project 9 Solo Exhibitions, on view until the end of the year at the Cultural Centre of Belgrade, feels like an important, almost defiant gesture. Nine different exhibitions spread across three gallery spaces form a program that shows that despite a lack of resources and the absence of structural support, the scene still has energy, ideas and artists willing to speak. To mark the release of the catalogue for the project, we spoke with its curators — Zoran Đaković Minniti, Vladimir Bjeličić and Senka Ristivojević, as well as with two participating artists, Nina Ivanović and Luka Trajković. Their reflections only confirmed that initiatives like this are far more than a line in a program. Keeping cultural life alive is, in itself, a way of giving the community back the sense that art still has a place and an audience.

Photo: Marko Ristović

“When you work within an institution, it’s your responsibility to protect and sustain ideas of critical resistance to established models of work and collaboration. That responsibility has only grown over the past year, as we’ve been confronted almost daily with the inconsistencies and the systemic crisis we live and work in, as well as with numerous individual and collective attempts to imagine a more solidary society. More participatory institutional models are probably the only way to strengthen institutions themselves, and, more broadly, the society around them,” Zorana begins, answering my question about how and when the curatorial team internally decided to change the exhibition format. She continues: “In June this year, we were informed that the annual budget for cultural institutions founded by the City of Belgrade would be reduced by 50%. The idea of a joint exhibition became a form of resistance to that decision, but also an invitation to reflect on how cultural institutions function in times of social crisis. We developed this idea together with the artists whose solo exhibitions were scheduled for the second half of the year and who were directly affected by the budget cut.”

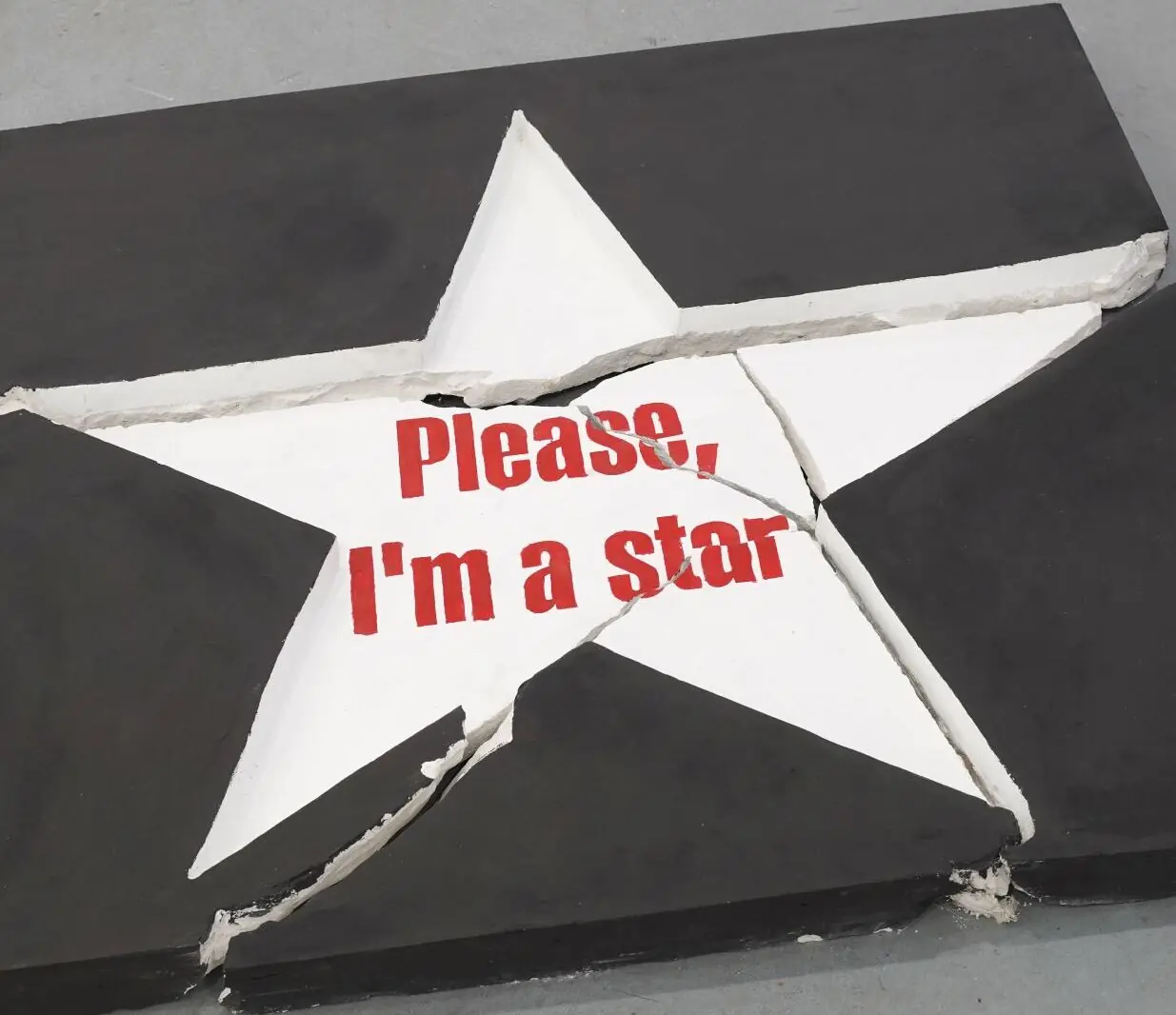

Since the exhibition brings together artists with very different sensibilities, aesthetics and mediums, I wanted to know how they approached the concept. Vladimir steps in: “It was very important to us to stay as faithful as possible to the idea of solo presentations, but from a new angle — the so-called joint format. In practical terms, that led us to rethink the display and find a way, with limited means, to create the impression of a single, cohesive whole. The textual inserts across all three gallery spaces are important reference points for visitors. We also wanted the manifesto to draw attention to the need to change the language we use when we talk about art. Hence the proverbs —

If you want the core, break the shell; What’s holding you back? or The song kept us alive, and to her we owe everything, cutting through the text and pointing to the current state of the local art scene, but also of society at large.

We need different kinds of stories and ways of experiencing art, outside the confines of professional discourse, because the world is changing at an incredible pace, and art and culture should be attentive to that rhythm despite countless obstacles.”

The obvious next question is about the compromises and challenges behind a project like this — and what, despite limited resources, remained non-negotiable. Senka responds with clarity: “Given the sweeping transformations shaping the world we live in, and the daily turbulence in Serbia, the conclusion of our discussions emerged on its own: our work, and the work of institutions themselves, cannot avoid the wave of change. At the same time, it opened up the question of what kinds of changes are needed for everyone involved in the contemporary art scene.” She adds: “With a strong dose of self-reflection, a response from the curatorial team was essential — as mediators and authors of the program — and the artists whose exhibitions were planned for the second half of the year joined us in that process. The format of nine solo exhibitions is a radical innovation for the CCB, and, I believe, for our scene more broadly. It may seem almost absurd when you enter the space: two exhibitions are missing, there are no extra partitions or clear boundaries, and each is reduced to one or a few works. With this approach, we wanted to unsettle and reorganize existing models of artistic presentation. In a world of absurdity, which has been building for decades and is now reaching its peak, what remains to us is conversation, questioning and experiment. The understanding and support we received from the artists were invaluable. In the difficult moment in which the CCB, our team and the wider community found themselves, it mattered that we could believe again that we’re not alone — that we have the capacity to join forces and work together.”

Photo: Luka Trajković

The curatorial team reminded us that coming together and working collectively is sometimes the only possible response. That shared impulse is exactly what shaped the dialogue with the artists. Because no matter how much we talk about institutions and models of functioning, at the center of everything are always the authors whose works carry the weight of the reality we must face, as well as the hope that it can be seen anew. This is why it was important to hear their perspectives too.

In conversation with Nina Ivanović and Luka Trajković, it became clear that the struggle to keep the artistic scene alive is happening on several fronts: in studios that are disappearing, in budgets cut in half, in ecologically devastated environments, in the pervasive sense of stagnation that has seeped into society. And yet, both artists, each through their own poetics, show that art still holds the power to widen our perspective, to question how we relate to the world, and to open up issues that are easy to sweep aside, but impossible to ignore forever.

Nina Ivanović has spent years closely following the fates of rivers, and this time she turned her focus to the Topčiderka. When asked what drew her to this particular river, she responds with disarming intimacy:

“Topčiderka is part of the neighborhood where I grew up, and even now I often cross the bridge over it on my bike, right near the spot where the river flows into the Sava. Because of that physical closeness, and the unbearable stench that rises from the river at certain times, I wanted to explore the state of the river my neighborhood is named after. Reading through the annual and monthly river monitoring reports on the City of Belgrade’s website, I found that Topčiderka is most often ranked in the fifth category of pollution (the indicator of the poorest water quality), and that various parameters exceed permitted levels. In the sediments, the most persistent excess of heavy metals is nickel. Several experts, journalists, and activists have already examined the pollution of the Topčiderka, and the problem is widely known, especially to people who pass through or spend time nearby, like the rowing clubs on the Sava. For those unfamiliar with the topic, I can recommend an older episode of the show Ciklotron — Krstarenje Topčiderkom.”

Topčiderka, detalj

In the curatorial text written by Senka Ristivojević, we see how the Topčiderka becomes a mirror of our relationship to nature. What I wanted to know was: when she walked the terrain herself, what was hardest to accept, the neglect, the pollution, or the indifference of institutions? “I wouldn’t say anything is hard to accept, it’s more that it’s tragic. Of course it’s all frustrating: that sewage is allowed to flow into rivers, that we don’t have wastewater treatment plants, that institutions are clearly doing too little or acting too slowly on these issues.

Restoring rivers is a long and expensive process, but essential for healthy life in an urban environment that is astonishingly rich in water.

The part of Duboki Potok I photographed in the forest, hidden from people, looks truly magical. It becomes the Topčiderka, which then, as it passes through populated areas, sadly loses all the qualities of what Senka Ristivojević beautifully described as a forest nymph. While researching information about our rivers, I found a wonderful revitalization project for the Topčiderka by the Institute of Forestry — a project that genuinely sparks hope. But the proposed method, which involves floating plant islands, can only work if the numerous sewage and industrial outlets are removed along the river’s entire 30-kilometer course.”

I can’t help but ask her about the link between her collective work on the 57th October Salon, which addressed the lack of working space for artists — and this exhibition, which deals with ecologically endangered spaces essential to all of us. Are the institutional failures that destroy studios and those that destroy rivers actually part of the same problem?

“The collective project Spaces for Work for the October Salon was a direct response to the circumstances we were facing. The curatorial team invited us to speak about the lack of working space from the position of artists who were, at that very moment, losing their studios in the Jugošped building. The river-related works also come from our everyday reality, the issue is right there, in front of us, and it is impossible to overlook. Naturally, there are many problems affecting all segments of society, but to me it is personally tragic that as a society we can’t keep our rivers clean, that the natural springs of drinking water in Belgrade, and there are many, are no longer safe. And I say this fully aware that in Zrenjanin there is no drinking water even from household taps, let alone from springs.

It’s obvious everything is part of the same problem: the absence of care, upkeep, maintenance and support — whether we’re talking about natural resources or artistic disciplines.”

When she speaks of the future, Nina remains grounded. She knows there are specific changes that would immediately improve artists’ working conditions: stable open calls, respect for deadlines, a larger cultural budget, access to subsidized workspaces. “A higher percentage of state and city budgets dedicated to culture, support for artists through subsidized studio spaces, there’s a lot that needs to be fixed, but even these few steps would already create a more stable position for artists, and with that, a more functional role for art in society.”

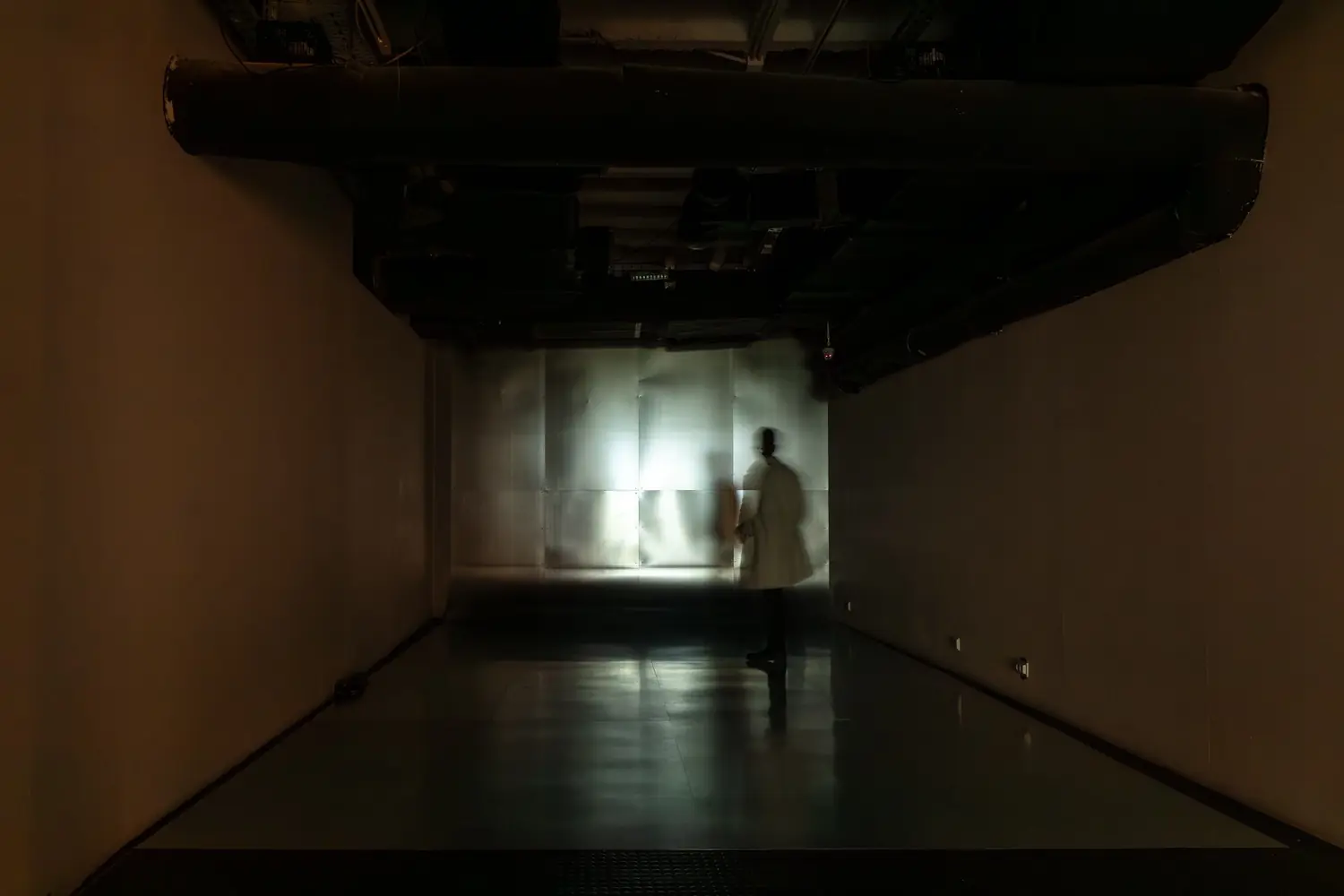

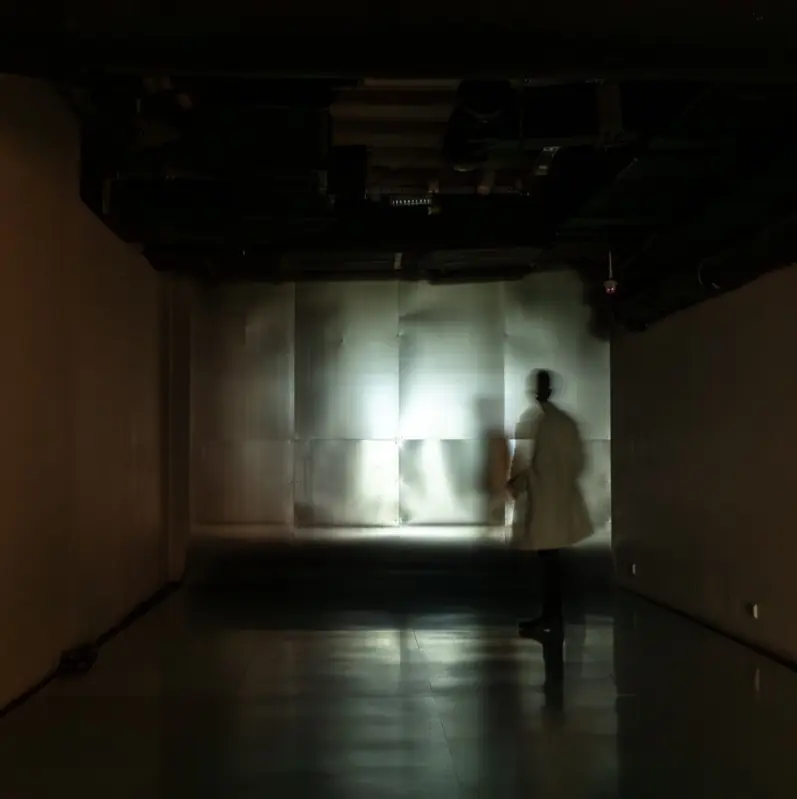

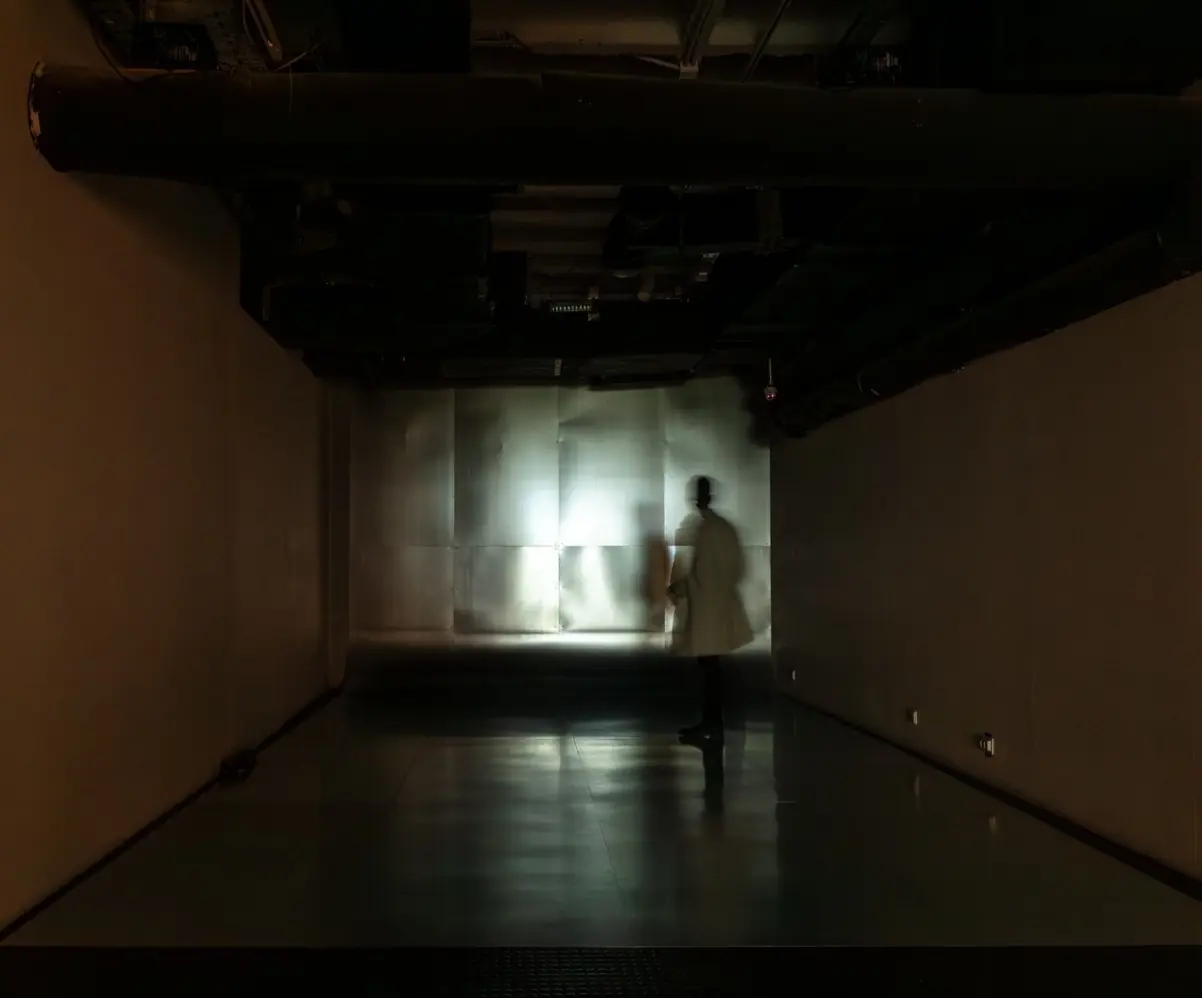

Luka Trajković comes from a completely different visual language, a cinematic one. His photographs resemble frames from a film that doesn’t exist, “frozen moments” that could be the beginning, middle or end of a story, depending on how you look. As he says, he comes from “the world of moving images,” so this project feels both close and unfamiliar. For each photograph, he prepared simple descriptions of scenes and characters, shaping them further through actors, friends and extras. No matter how much he plans, he always leaves space for what happens in the moment, which is why some of the shots turned out completely unexpectedly.

Photo: Luka Trajković

He only recognized the atmosphere running through the series once he had finished it: a sense of standstill, uncertainty, a tension you simply can’t ignore. “While I was working on the series, I was building that atmosphere intuitively, without overthinking how it should feel. But when I started preparing the exhibition and went through all the material again, I realized how closely it reflects the situation we’re all collectively living in. A few years ago, the atmosphere wasn’t much different, we were just less conscious of it. Today, it’s impossible to escape. In that sense, I think my work responds to this atmosphere, then more indirectly, now more directly. Photography can absolutely be a space of resistance. Since its invention, the image has held enormous power in society, both as a key form of communication and as a tool for individual expression, a voice,” he says. His words lead me to ask about the working conditions artists face, conditions that are often unstable and rarely encouraging. Does he feel there’s room for growth, or is that “frozen frame” closer to reality than we’d like to admit? “Absolutely closer to reality than we’d like. This exhibition itself was realized within the framework of the 9 Solo Exhibitions, all in a single slot, because the Cultural Centre of Belgrade’s annual budget was cut in half in May, halfway through the year. There was simply no other way for all the artists to exhibit individually. There wasn’t even a call from the Film Center of Serbia this year, everything is at a standstill. Only commercial projects or projects by politically aligned authors are being supported. The cultural scene is in visible crisis, just like the society around us, while many contemporary creators face existential problems, without the space or conditions to work.”

To close the interview on at least a slightly hopeful note, I ask Luka what he most often tells his students at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Belgrade, and what he wishes someone had told him when he was studying. “It’s beautiful when you see seven students with seven completely different approaches and styles. It reminds us every time how unique each person’s expression is, and how important it is to nurture that initial point of view. It will, of course, evolve with time, work, experience and formal education, but its root always stays there. That’s something I try to emphasize — that sometimes they just need to follow that intuitive feeling. We’re here to teach them the basic rules and tools of visual expression, but they shouldn’t feel bound by them. The most creative solutions often come from limitations, which we all face — in our student years, later as professionals, and especially in author-driven work in our environment.”