Everything is political. I know this might sound too radical for those who like to say they’re “not interested in politics,” but the truth is that, one way or another, we’re all involved in it. If we don’t engage with politics, it engages with us — we are inseparable from it, whether we like it or not. In its very essence, the word refers to the polis, the city or the state — in other words, everything that concerns the community. To be political, then, means to be aware of the community, to act responsibly toward others, to think critically about power relations. In today’s world, politics is no longer confined to parliaments or institutions. It has descended into the everyday, seeping into every corner of society — anywhere power, the body, or identity are at play. In other words: everywhere, from social media to fashion, to our most intimate relationships. Every decision about the body, labor, love, identity, or space is a matter of collective life — and that naturally includes sex and sexuality.

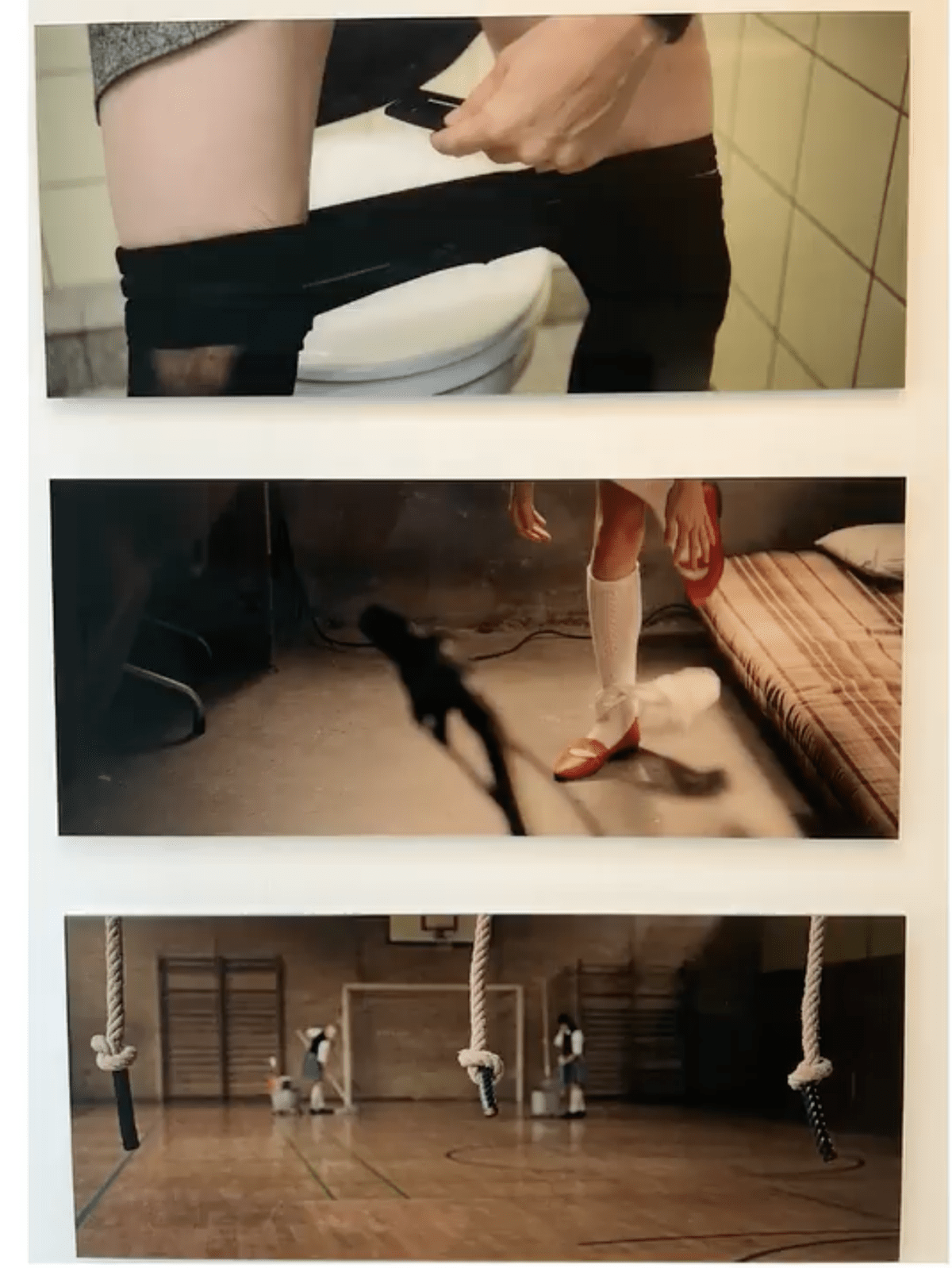

As Paris shifts its attention from fashion to photography with the upcoming Paris Photo, one of the highlights of the fair — the exhibition Sex and Politics, which opened on November 13 at the Bastille Design Center — invites viewers to explore one of the most charged intersections of contemporary life: the point where sexuality meets power, and the body becomes a space of political and cultural negotiation. The project brings together an international group of artists whose works examine sexuality as a political terrain — a site where personal freedom, social norms, and cultural narratives continuously intertwine, clash, and evolve.

Related: An exhibition capturing the bittersweet chapter of life we remember with nostalgia

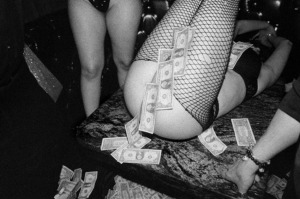

Elizabeth Waterman

Elizabeth Waterman

In his book The Plague of Fantasies — the theoretical cornerstone of the exhibition, excerpts of which are also featured in the catalogue — Slavoj Žižek explains that this is precisely how sexuality functions: “It is not merely a matter of private pleasure or personal freedom; it is a space where ideological assumptions, social hierarchies, and symbolic power are negotiated. Within the sphere of sexuality, the boundaries between private and public, between personal desire and social constraint, are constantly shifting.” With that in mind, while speaking with the curators, I couldn’t help but reflect on our collective illusion that sex is a deeply intimate act — even though it is, paradoxically, also one of the most socially regulated and surveilled aspects of life. What, then, are we really talking about when we talk about sexuality? “Like many others, we once believed in the illusion that sexuality is a private matter — something intimate and personal. But over time, through theory, art, and experience, it became clear that it is one of the most monitored, regulated, and frequently exploited aspects of human existence. Sexuality is political because it reflects how societies treat difference, control, shame, power, and freedom. We’re not talking only about biology or intimacy — we’re talking about power. Sexuality is never neutral. It’s shaped by language, politics, institutions, and cultural norms. When we talk about sex, we talk about how people are allowed to exist, to express desire — or to be punished for it. Sexuality is as much about systems of control as it is about personal feeling.”

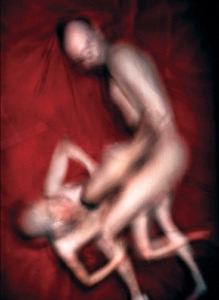

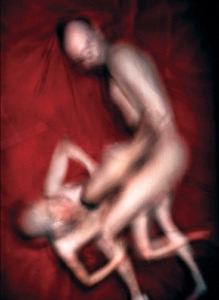

Lars von Trier, Nymphomaniac

As they spoke, I immediately thought of Anaïs Nin’s line that “the erotic is one of the basic means of self-knowledge, as indispensable as poetry,” and of Foucault, who connects the history of sexuality with the will to knowledge. Sexuality is inseparable from knowledge and self-knowledge — which is precisely why it is often suppressed, censored, or silenced, because knowledge leads to liberation. Thus, a society’s relationship to sexuality becomes a mirror of its mechanisms of control. “Nin was right,” say Slavica and Danila. “Eroticism isn’t a distraction but a diagnostic tool. It’s poetry, but it’s also politics, identity — sometimes even revolution. The way a society treats sexuality reveals everything about its fears, boundaries, and hypocrisies. In repressive systems, the sexual becomes a space of subversion. In more liberal societies, it’s often commercialized, yet it continues to provoke discomfort. You can’t speak of democratic rights or freedom without including the right to express, define, and live one’s sexuality without fear, shame, or institutional violence. When sexuality is liberated, it destabilizes authoritarian structures. That’s why it is so often censored or controlled.”

With that in mind, I asked how they interpret the current moment, which seems increasingly reactionary even as it speaks louder than ever about ‘freedom’ — freedoms that I’m no longer sure are real or merely performative.

“We live in contradiction,” they tell me. “On the surface, there’s greater openness, visibility, and conversation. Yet beneath that lies a growing moralization, surveillance, and new forms of shaming. Control hasn’t disappeared; it has simply become algorithmic — subtler, more pervasive. At the same time, people are more self-aware and more capable of questioning norms. It’s precisely because of this tense balance that the exhibition carries such relevance today.”

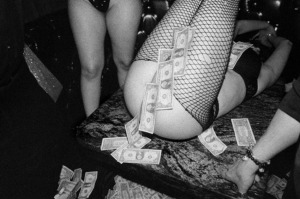

Beyond the growing number of authoritarian systems where a queer kiss or a trans body still invites censorship and ‘reeducation’ of desire, capitalism stands as another adversary. If it has succeeded in commodifying desire, commercializing it — where, then, does authentic desire still exist? “Desire is shaped by images — and today, more than ever, we are saturated with them. Social media, pornography, advertising — they don’t just reflect desire, they manufacture it. Capitalism has taught us to want what can be consumed, posted, sold, and compared. But desire also resists. It sneaks into dreams, taboos, irrational fantasies. That tension between constructed desire and authentic longing is at the heart of this exhibition — in what cannot be captured. In moments of unmediated intimacy. In fantasies that aren’t for sale. In bodies that don’t fit. In art that makes you uncomfortable or uncertain. Authenticity isn’t about returning to some ‘pure’ desire — it’s about recognizing that desire has always been fractured, contradictory, and a little dangerous.”

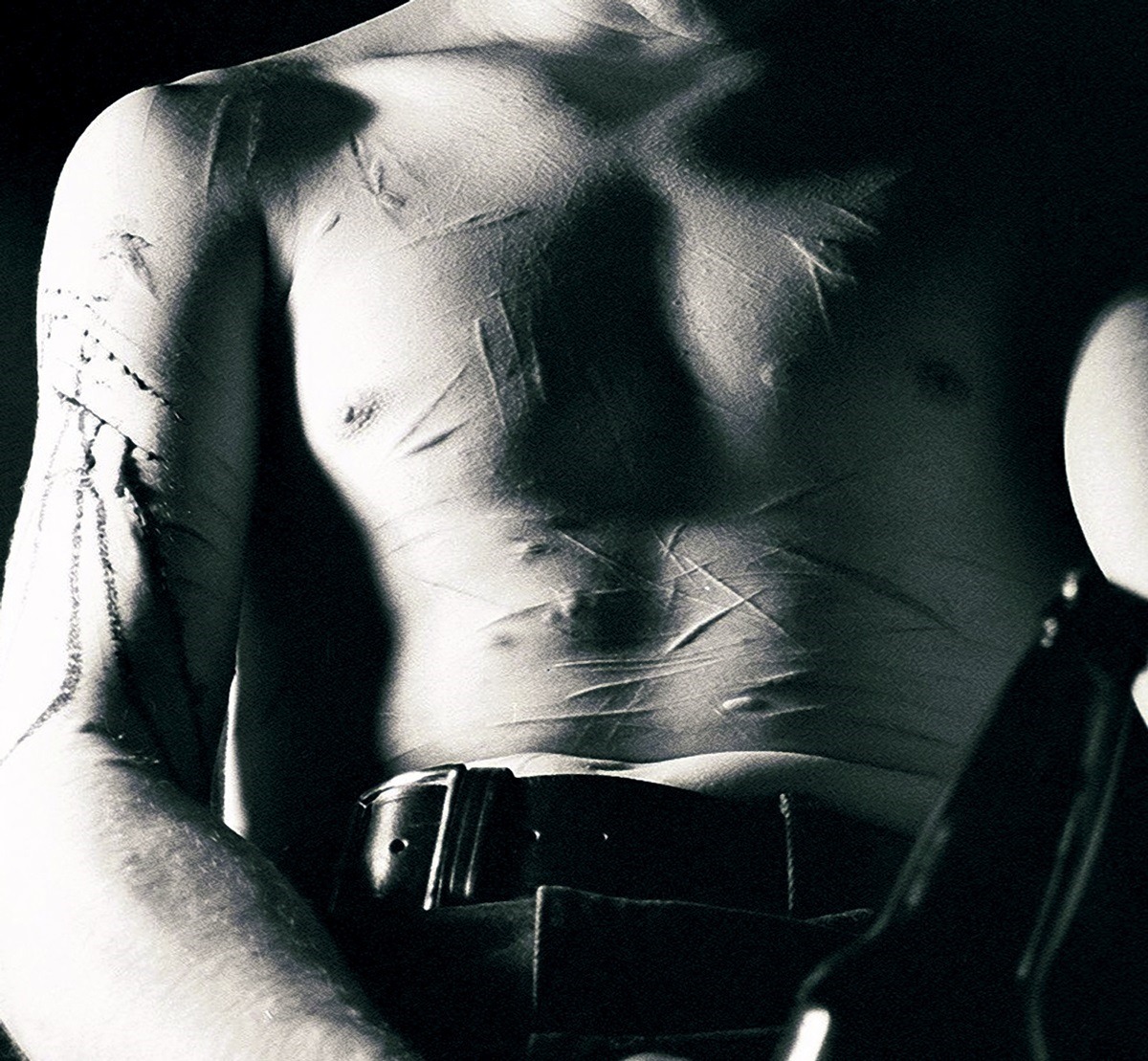

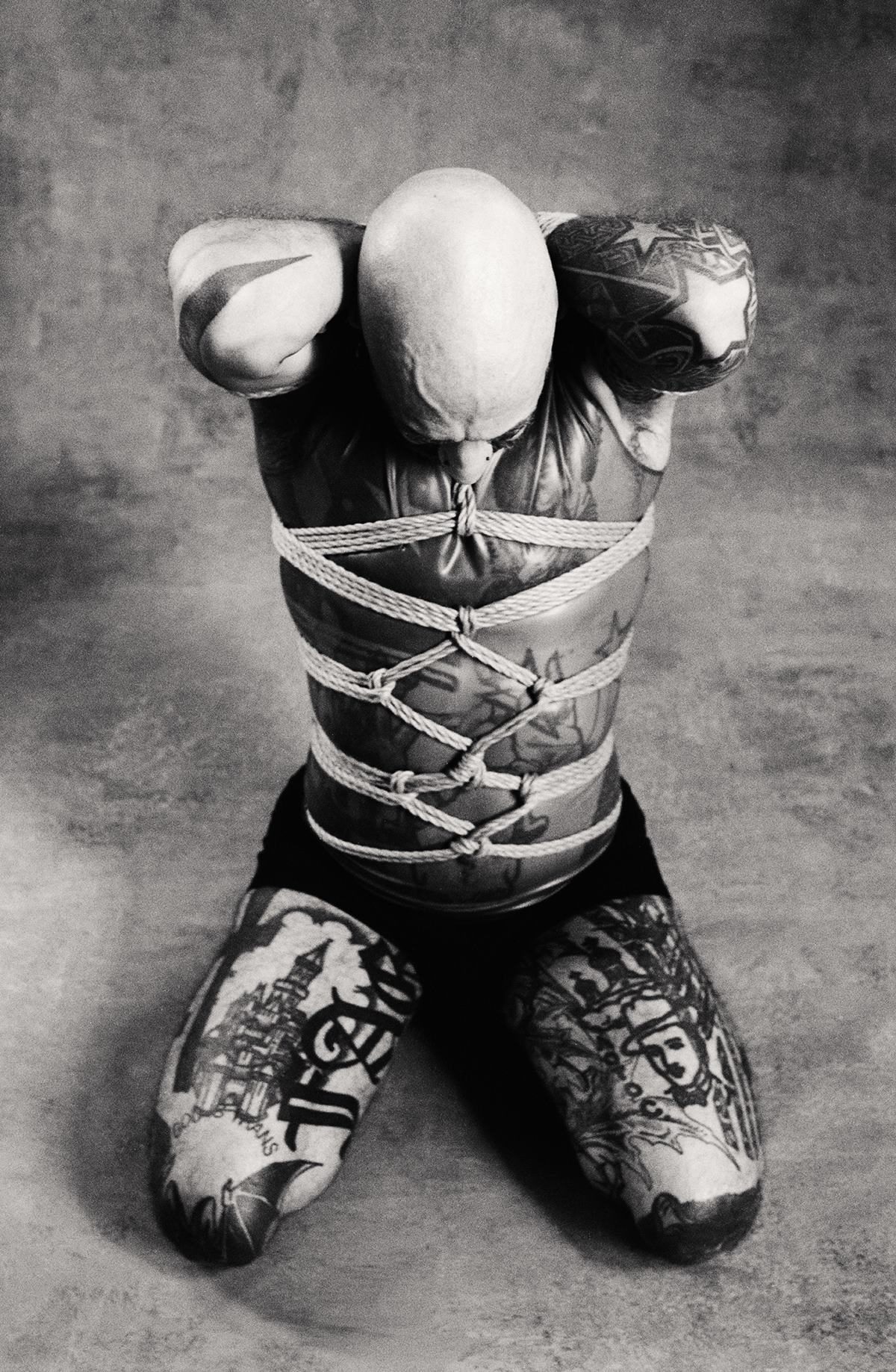

Antoine d’Agata

I nod, because I couldn’t agree more — yet I share their unease about how little feels truly authentic anymore, even desire itself. In that sense, I asked where fantasy fits into this landscape. Are taboos and fetishes perhaps the last remaining spaces of true freedom? “Fantasies are the grammar of desire,” they reply. “They reveal what cannot be said, what is repressed, or what society forbids. Žižek often says that fantasy structures our reality. In this exhibition, fantasy is everywhere — in Roger Ballen’s staged bodies, in Witkin’s erotic surrealism, in von Trier’s cinematic perversion. Fantasy isn’t an escape from reality; it’s a key to understanding it. Capitalism, however, loves to package transgression. The real question is: can taboos still shock us? Can they still protect something raw, unspoken, unprocessed? Perhaps they are the last untamed territories of the psyche. Taboos and fetishes remind us that desire isn’t rational. It doesn’t obey norms. It resists being productive or polite.” And maybe, today more than ever, a little resistance to formalism is exactly what we need.