When, around this time last year, after days and nights of preparation for a major event, I finally managed to change my clothes and step out among the guests, I was convinced that none of the storms raging inside me were showing on my face. Darling, there is an aura of stress around you, one of the women close to me whispered just as I had started to believe I was excelling at the discipline known as mingling, a word I had only looked up on Google a few years earlier. It was not much better recently when I returned to public gatherings after a long break. Anxious thoughts at a table of a hundred people flooded me so completely that I felt as if the ground were slipping from under my feet. It was closely connected to the fact that the introvert in me had grown very comfortable in the working from home system, distancing herself even more noticeably from the everyday life in which she must appear impeccable in the eyes of others, whether clients, collaborators, colleagues, guests, or even family and friends.

When I first heard the term performance anxiety, I began to revisit every memory of that emotional whirlwind before an important event, public appearance, business meeting, wedding, or exam. The type of nervousness that, on a deeper level, actually comes from the desire to make an exceptional impression. News that beta blockers have begun to be prescribed for this condition in the United States, even though they were originally intended to regulate abnormal heart rhythms and manage cardiac dysfunctions, only confirmed to me how far this phenomenon has gone, much like the rise of Ozempic. Beta blockers act on so-called beta receptors, structures in our bodies that respond to stress hormones such as adrenaline. When these hormones bind to the receptors, heart rate increases, blood pressure rises, and a person may feel uncomfortable sensations like stage fright. Beta blockers bind to those same receptors and prevent the hormones from taking effect. Put simply, we block ourselves from noticing stress at all. We eliminate the problem instead of regulating it. And we know how misleading that can be. In my conversation with Ana Perović, a psychotherapist, psychologist, and host of the podcast U raljama osećanja, we talked about how to overcome the many shades of this condition.

Where does performance anxiety come from?

It seems to me that the term performance anxiety is awkwardly translated here as anxiety about public speaking, heavily focused on productivity and on the idea that, in situations where we need to prove our competence, we deal with anything that stands in the way of our goal, including our inner feelings. This American cultural norm is carried over to us as a symptom of a capitalist society. In that process we instrumentalize ourselves, or in other words, we treat ourselves like a service or a machine that must automatically meet the expectations that life places before us, as well as the expectations we place on ourselves. And we must do it with a smile, removing along the way any sign that we might not feel entirely comfortable, that we might have fears, that we might not feel at ease, Ana tells me. She emphasizes that this bundle of anxiety combines fear of the unknown, which feels potentially threatening, with the pressure to achieve something, succeed at something, or demonstrate our competence.

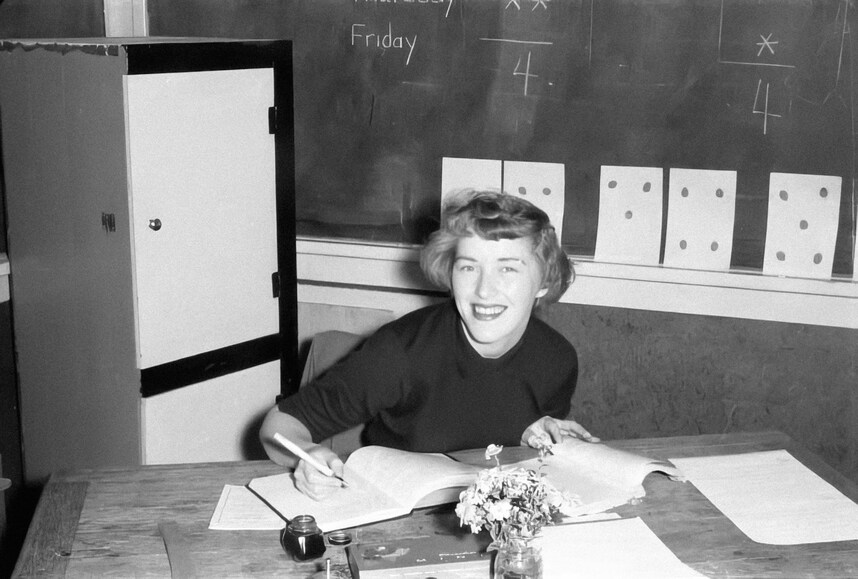

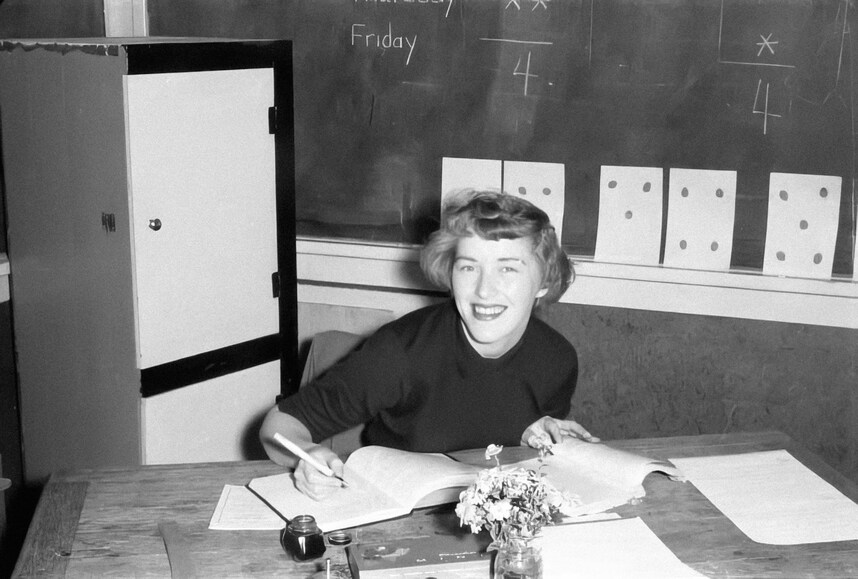

Photo: Galt Museum Archives

Acknowledge your vulnerability

tell her about my own experience, which is closely connected to social anxiety. This phenomenon does not affect only those in public professions such as actors and singers, although they certainly experience it strongly, but also anyone who is publicly exposed or surrounded by large groups of people because of the nature of their work. Even if we handle it better, the absolute expectation that we will feel good all the time, every single day, is unrealistic, even if we do not have heightened anxiety about these kinds of social situations. What we are really talking about is the fact that all of us are vulnerable, on a very human level, to this constant exposure to others. Especially when we are presenting our expertise or something important about who we are, so no matter how capable we may be, we will still need occasional validation. This brings us to a key point. When this type of anxiety appears, each of us has a choice: when an unpleasant state arises, we can pause and look at it with some curiosity, or we can try to eliminate it instantly, which is really suppression.

This choice is not always simple because many people work in industries full of tension, stress, overstimulation, or constant interaction. We then find ourselves thinking that being curious about what is happening inside us is a luxury we cannot afford because we do not have time, because others expect something from us, because we must rise to the occasion. This puts us at risk of getting used to treating our inner states as something to be removed, minimized, or pushed aside in whatever way we know, in order to reach the goal ahead of us, especially if we have had five meetings in one day, if our schedules are packed, or if we are also parents.

Train your psychological muscle

The point is that we should not give up on training our psychological muscle. That is what we call emotional regulation, which is a more demanding path toward managing our states, but also the only path that deepens our trust in our own capacities in the long run. That trust comes from knowing that we can move through experiences and navigate them, that we can rely on ourselves, and that whatever happens, we have a place within us from which we can transform those states into something more manageable. There are of course many people who, in certain conditions and phases, need medication in consultation with a psychologist or psychiatrist, but that is similar to using a crutch when you sprain your ankle. It is an external support while you also go to physical therapy. We need to try to restore the capacity of that muscle, in this case the psychological one, because strengthening it is a significant part of therapeutic work.

As someone who often reacts too dramatically, I touch on these concepts frequently in therapy, including the difference between emotional regulation and emotional control. If we try to control something, we approach it as if we need to restrain it and keep it hidden, which comes with side effects, because we interpret it as something threatening. If we regulate, we first become aware of the signals, recognize what we are feeling and experiencing in that moment, name those states, and learn to create an inner dialogue with them so that we can transform them into something more tolerable. Hey, a part of me feels a little threatened here, or angry, and needs to feel a bit safer. We learn the language of needs and the signals behind our states, and by doing so, we demystify them. We cannot always go through that process on our own and often need psychological support, especially considering that many of us grew up in a region where society was fighting for basic survival, without the space or time to develop emotional and psychological capacities.

Photo: Galt Museum Archives

Do You Have an Inner Observer?

If you recognize the voice inside you that constantly criticizes, questions, and points out everything you said or did wrong, you carry an inner observer who usually communicates with you in a destructive, not constructive, way. Our task is to intercept that voice with the awareness that its perception of us is filtered through specific things it pays excessive attention to. Imagine perceiving anyone in such a selective way, putting their entire existence under a magnifying glass and zooming in only on the parts that could have been better or that are imperfect, Ana explains. The real question is whether the comment we direct at ourselves helps us reach our goal. If it does not, then what we have is an inner saboteur. If it does, there may be less harsh and more well-meaning advice we can offer ourselves to improve something.

What Image Are You Building of Yourself on Social Media?

Performance anxiety is also tied to the focus that capitalist society places on how productive we are and what kind of persona we present at work or at home. Seeing ourselves as machines will create problems not only in professional projects but also when we become parents who impose on themselves the idea that they can and must do everything. This is usually when something breaks and we find ourselves asking when we developed a relationship with ourselves that strips us of the right to be human. As if we are exerting oppression over our own lives.

Social media intensifies the feeling that we are an unfinished project that must be constantly improved in order to be presented somewhere. There is a phenomenon where we do not compare ourselves to the actual lives of others but only to the fragments they choose to show in the online world. And then something even stranger happens. We begin to feel as if we cannot live up to the standard we set through our own self-presentation. A form of alienation emerges, a split from that person online, because we are not, at our core, that endlessly curated and polished version. If we dedicate even our behind the scenes time to refining that image, when do we make space for our imperfect, vulnerable self, for introspection, and finally for the question of what is truly important and necessary for us, what kind of life we wanted for ourselves, and how to create room for it.

Photo: Galt Museum Archives

The key question for overcoming performance anxiety

In most cases, when we feel this kind of anxiety, we perceive the situation we are in as potentially threatening to our identity, reputation, or the way others might interpret who we are. It is not a matter of life or death, Ana tells me. We first need to become aware of whether a part of us approaches the situation as if it were, possibly because of earlier experiences we lived through long ago, in school, when we first encountered a moment of exposure and felt the panicked sense that so much depended on the outcome, whether it was answering a question, performing, or competing. When we recognize the parts of us that react as if our entire existence depends on that moment, and we dig a little deeper beneath that belief, we can remind ourselves, as adults, that these situations may be high stakes and important to us, but they are nowhere near as threatening as they feel. In therapy, the work is often about restoring a sense of safety, which is very individual, but even asking a simple question such as, What would help me feel safer in this situation, can offer a helpful direction.

A return to ourselves

Beneath all of this lies the realization that we are not truly connected to ourselves. Somewhere along the way, we have become disconnected. Because of that, we often look for answers outside of us. We skip the simplest question: What are the moments in our lives that bring us back to a sense of meaning, whatever they may be. It seems we are living in an era in which we are not attuned to ourselves, which leads to a deeper issue. Why do we enter or remain in certain relationships, and why do we live a life that feels chosen by someone else. This is why it is important to emphasize that these answers will not come from anyone else in the world, not even from a psychotherapist, who can only open the door. They ultimately come from us. And that is essential if we want to talk about building a counterweight to living as servants of capitalist expectations while suppressing our own emotions.