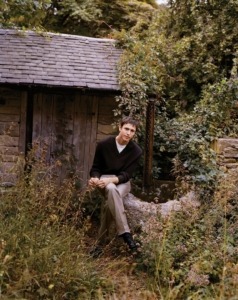

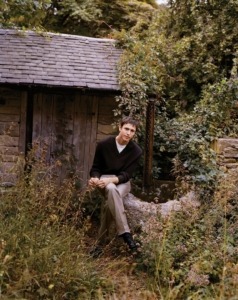

“Be down in a minute!” a cheery voice crackles through the intercom. It’s a balmy late-July afternoon in east London, and I’ve just rung the buzzer of an old schoolhouse, now a hub of offices for fashion types. Within moments, the rangy 29-year-old actor Harris Dickinson bounds down an exterior staircase and shakes my hand. “Did you come far?” he asks.

We’re a few miles away from the London film-industry hub of Soho, in a neighborhood of modish restaurants and cafés where Dickinson has situated his production company, Devisio Pictures. He’s practically in camouflage here, in a white T-shirt, cargo pants, and Adidas Sambas, and his office vibe is that of a scrappy but flourishing start-up: vintage film posters, potted plants, a kaleidoscopic array of herbal teas. “I made the first rough cut of Urchin on those,” Dickinson says, pointing toward giant monitors on a desk in the corner.

Urchin—which Dickinson wrote and directed—premiered just two months before at Cannes, where Dickinson processed down the Croisette in double-breasted Prada, paparazzi flashbulbs lighting his Modigliani features. We’re a million miles from all that here. “I’d never been so nervous in my life,” Dickinson says. “I was terrified. I felt like I was having a nervous breakdown 10 minutes before we went into the screening.”

But the reception was ecstatic: Urchin, a deeply affecting drama about Mike, a young homeless man in London struggling with addiction and mental health issues, took home both a film-critics prize and a best-actor award for its star, Frank Dillane.

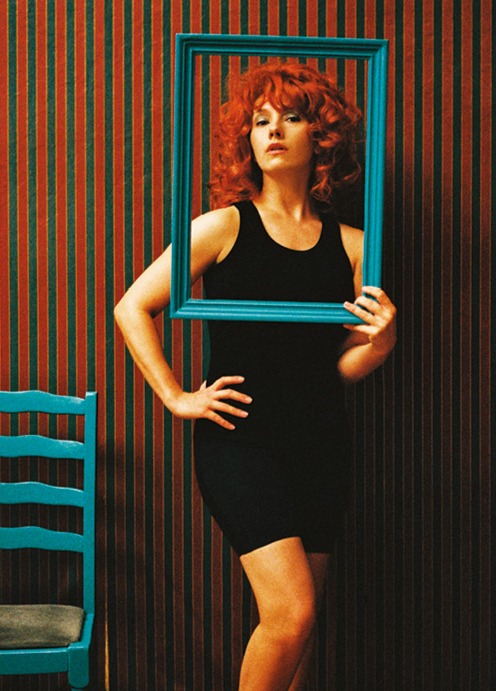

Dickinson describes the days following as a whirlwind—“bonkers,” in his soft London accent—as he and Dillane were overwhelmed by praise and promotional duties. (Though there were breaks, like the Cannes after-hours party at which his girlfriend, pop musician Rose Gray, and their friend Charli XCX took over the DJ decks.) “Regardless of whether people admit it,” Dickinson says of Cannes, “you’re looking for someone to go, ‘Okay, yeah, this worked. You’re not completely mad. This isn’t a useless endeavor.’ So that felt good.”

Dickinson wasn’t the only actor making a festival directorial debut (Scarlett Johansson and Kristen Stewart also took the plunge). Did he feel the scrutiny—even skepticism? “For sure,” he says. “But I also read a review that was like, ‘He proves that he can do more than order milk.’ That was such a reductive, dumb fucking headline.

I’ve been wanting to make films my whole life, and I’ve earned my stripes to get to this place.

Dickinson broke out in Eliza Hittman’s 2017 indie hit, Beach Rats, where he played a wayward Brooklyn teen struggling to come to terms with his sexuality. His talent for a volatile vulnerability and grit saw him through performances as troubled tough guys in Where the Crawdads Sing and The Iron Claw. (His turn as a preening himbo fashion model in Ruben Öst- lund’s Palme d’Or–winning social satire Triangle of Sadness marked an interesting diversion from type). And then there was his performance opposite Nicole Kidman in last year’s Babygirl: as a young corporate intern attempting, through guile and awkward artlessness (the aforementioned milk-ordering),to seduce his boss into a BDSM-inflected affair.

Setting acting aside to focus on directing Urchin (from a script he began writing five years ago) was a “weird switch” he says. As a fast-rising actor from a working-class background in the Highams Park suburb of east London—Dickinson’s mother is a hairdresser and his father a social worker—he spent much of his early career taking jobs that, “regardless of their artistic importance in the world, were giving me opportunities.” Directing would require turning down roles at a moment when the funding for the film was still in flux.

“Urchin was a leap of faith. “Something I had to do,” he says. “I couldn’t escape it.”

Dickinson’s directorial ambitions run deep. At 10, he was making skate-boarding films on a Sony Handycam. By 14, he was making short films influenced by the work of filmmakers like Mike Leigh and Shane Meadows. “I would write quite heavy, weighted scripts,” he says, with a touch of embarrassment. At the end of high school, he considered joining the Royal Marines, but thanks to the encouragement of a coach at Raw Academy—the performing arts club he attended—he began auditioning for acting jobs. Acting “felt like something I could do without spending money or having to get people to help me make my films,” he says.

The years of scrapping for income gave him the tenacity he needed to walk into the BBC and pitch his short film 2003, a portrait of a young man attempting to reconcile with his alcoholic father before heading off on deployment at the eve of the Iraq War. And it was his curiosity about filmmaking that partly led Halina Reijn to cast him in Babygirl: “I knew he’d written a script and was going to direct it,” she explains. “I knew he was interested in the whole process of filmmaking,” The fascination was visible in how he ran the Urchin set, says Archie Pearch, a longtime friend and cofounder of Devisio. “I remember in the first week, watching someone get something out of a van and then Harris going over to give them a hand,” he says. “There’s no ego.”

That’s probably why the aspect of Urchin Dickinson feels most uncomfortable talking about is that he’s actually in it: playing Nathan, a duplicitous friend of Mike’s from the streets who later finds himself in a transactional romantic relationship with an older woman. This wasn’t planned. The actor cast for the role dropped out one week before they began shooting, and Dillane encouraged him to step in. “I sort of had to be like, ‘Mate, you’ve got to be in this movie,’” says Dillane, 34, who has the same cheeky, effete charm as the film’s protagonist. “You know the character inside out,” Dillane remembers saying, “you know what is required. You’re a great actor.”

When I mention this to Dickinson, he sighs. “I felt like a bit of a dick being in my own film, if I’m honest with you. ‘Here I am, I’ll do it! Fucking jazz hands and all!’ But the role is small enough that it is fine. It’s Frank’s film.” It was a five-week shoot on a Lilliputian budget—constraints that Dickinson says he was “energized” by.

“My brain loved being that active. I’ve been craving that level of engagement and responsibility.”

(He also came to enjoy the routine of editing—going to the office to cut the film—and then being back at the east London home he shares with Gray and a British shorthair cat, Misty Blue, in time for dinner).

For Dickinson, the greater challenge lay in finding the right tone to strike around the film’s sensitive subject matter. Dickinson is a longtime volunteer at a London homeless charity, and while he doesn’t want to bang the drum about it, he does recognize that it’s important he cites that experience as having informed the film. “It’s a tricky one,” he acknowledges. “That work became a part of my routine in order to feel like I was not the useless human being that I am.” His father’s social work career was an inspiration too. “It is important for people to know that I’ve done my due diligence in that world.” Indeed, for his Urchin photo-call at Cannes, Dickinson wore a T-shirt aimed at comments made by the former British home secretary Suella Braverman:

“Living on the streets is not a lifestyle choice Suella. It’s a sign of failed government policy.”

“Whatever I can do to try and shout about issues, I’m going to do it,” he says. “It’s not a big deal for me to wear a fucking T-shirt on a beach, you know what I mean? I think we’re getting to a time when people need to be called out. We are past the point where politicians get to just get away with stuff.”

Ušli smo u složeno pitanje klase, a Dickinson predstavlja sve rjeđu vrstu britanskog glumca – radničkog tipa glavnog junaka poput Alberta Finneya i Terencea Stampa, ili, u novije vrijeme, Jamesa McAvoya i Clivea Owena – čije je skromno podrijetlo oblikovalo filmove u kojima su sudjelovali. Izvješće Laburističke stranke Britanije iz 2024. pokazalo je da je gotovo polovica britanskih kandidata za vodeće kulturne nagrade pohađala privatne škole, a nakon 14 godina konzervativne vlasti u Ujedinjenom Kraljevstvu, izvori financiranja umjetnosti drastično su smanjeni.

We’re into the complex issue of class, and Dickinson represents a dwindling breed of British actor, the kind of working-class leading man like Albert Finney and Terence Stamp—or more recently, James McAvoy and Clive Owen—whose humble beginnings informed the We’re into the complex issue of class, and Dickinson represents a dwindling breed of British actor, the kind of working-class leading man like Albert Finney and Terence Stamp—or more recently, James McAvoy and Clive Owen—whose humble beginnings informed the When I ask Dickinson about all this, he takes a moment to consider his reply. “You see it a lot,” he says. “You see privilege prop people up in various ways, and I don’t blame anyone for that. But it’s difficult if someone does not have financial means while they’re trying to build a career.” How do filmmakers and artists of any kind sustain themselves while things are waiting to get made? “Or potentially not getting made,” he says. “How does one do any of that without support?”

Those who know Dickinson well return to the same theme: “Humble and very grounded,” says Reijn. “Humble and very kind,” says Pearch. “I trust him implicitly,” says Dillane. “He’s navigated this world so beautifully.” Part of that lies in the way he instinctively maintains his privacy: Though he’s happy to answer questions, his one request (made with the utmost politeness) is that I don’t get too specific about where his office is. He has no issue waxing lyrical about Gray, for instance, whose debut album was released earlier this year to acclaim. “I love gassing her up,” he says, grinning. “When I see Rose doing her thing, I’m just in awe of it, really.”

And next up, of course, is Sam Mendes’s epic four-part Beatles film series in which Dickinson plays John Lennon. He still sounds surprised that he was even cast in the project. “I had immediate imposter syndrome,” he says. “But Sam is such an intelligent, kind man—the best person to do this.” How has it been, working with the other actors (Paul Mescal, Barry Keoghan, Joseph Quinn)? “Yeah. Yeah.” He considers his words (and probably an NDA) before replying, with a knowing smile: “They’re alright, those guys.”

He’s been working sporadically on a new screenplay, but the Beatles films consume most of his time—and likely will until their release in 2028. “I’m writing, but I think my energy works best focused on one thing at a time,” he says. This is, in fact, a very rare day off, and what does that look like for Harris Dickinson? “I’ve got a good group of mates that all live in London. We’ll go to the park, have a little drink, go for a little walk, the usual shit, man. Go to the cinema. Very boring.”

So boring, that the reason he has to head off is for a dental appointment. As we leave the office, a pair of young women in Breton tops pause and look up from their lunch, registering the tall, boyish figure leaping down the stairs two at a time. A flash of recognition appears on their faces; then, they return to their lunch, unbothered. Just a nice guy headed to the dentist.

Photo:Brett Lloyd