Although you’ll usually see me wearing little to no jewelry, I often describe myself as a jewelry lover. I have to admit that my laziness (and the fact that I’m not a millionaire) is probably the real reason I’m not draped in gold or at least something that looks like it. The first time a piece of jewelry truly took my breath away was in 2018, when I watched Ocean’s 8 and saw Anne Hathaway wearing the spectacular Toussaint diamond necklace, which Cartier pulled from its own archives for the film. That moment, aside from making me love the movie even more, opened the door to another obsession — Cartier, as a symbol of eternal elegance and unparalleled craftsmanship.

Founded in 1847 in Paris, Cartier has, over the centuries, become synonymous with elegance and opulence — but also with an aesthetic that was never merely about wealth. Its creations have always carried the spirit of their time, from royal courts to the silver screen, where they have brilliantly played the dual role of status symbol and work of art. So, a few years later, Wes Anderson’s film world once again reminded me of my Cartier fascination. His realm of symmetry, pastel tones, and meticulously controlled nostalgia perfectly overlaps with what Cartier has always embodied: time that doesn’t pass but folds in on itself, where beauty exists for its own sake.

Fondation Cartier

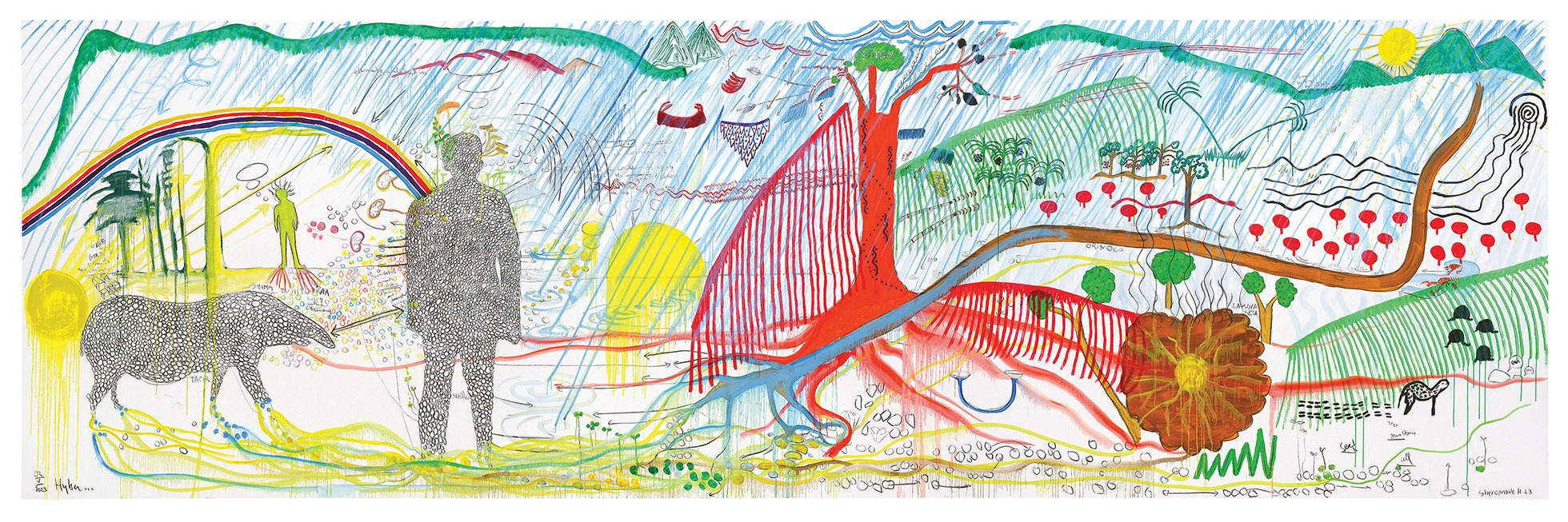

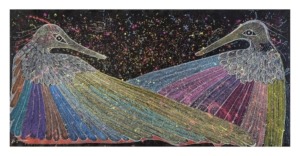

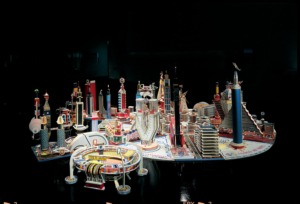

In that spirit, a few days ago, the Fondation Cartier opened its new museum space in Paris, unveiling the exhibition Exposition Générale, which once again placed the brand at the center of my attention. Foundation director Chris Dercon explained that this was the first exhibition through which they wanted to “open the collection,” selecting around 600 works out of 4,500. “Of course, we had to make choices,” he said. “But the goal was for visitors to truly see what lies behind the walls of the foundation.” That was, in fact, the first question I would have asked myself: how does one choose what should represent the essence of a world like Cartier’s? What does it mean to select the “right” pieces in a sea of objects that are already exceptional by definition? Is the choice guided by emotion, history, or aesthetics? That process of selection, at its core, reminds me of what Cartier has done throughout its existence — refusing to draw a line between art and craft, constantly re-examining where that boundary lies. Selection isn’t just a matter of taste; it’s a way of showing how each object, no matter how lavish, carries within it traces of time, of the hand and the gaze that created it.

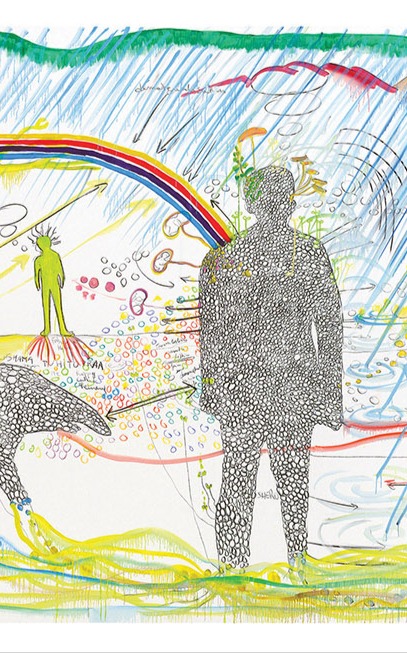

The new Fondation Cartier space is more than an architectural shift — as curator Béatrice Grenier puts it, it’s “a transformation of the institution itself.” The main challenge was how to modernize a historic Haussmann building while inventing a new architecture for exhibiting art. Designed by Jean Nouvel, the building has become almost a sculpture in motion: there are no walls, no ceilings, everything moves and everything is open. Nouvel created a space whose architecture responds to art rather than overpowering it.

“I’ve always imagined the Fondation Cartier as a refuge, a welcoming place where everyone is invited to discover the art of today,” Nouvel said at a recent press conference, describing the building as “a large workshop that adapts to artists, their works, and ideas.” Indeed, the new address at 2 Place du Palais-Royal, in the former Grands Magasins du Louvre building, feels more like a space in motion than a traditional museum: five movable platforms, glass facades that open onto the street, and a sense that art spills out into the city. Dercon recently remarked that “the spirit of the new Fondation Cartier is not that of a cathedral where one must always do more, always go bigger.” I wondered if that meant they didn’t want the space to impress with size (even though it does), but rather to remain intimate, open, and flexible for artists. The answer lies in Dercon’s wish for the foundation to be a space that breathes with art, not an institution that imposes grandeur upon it.

As I sit in a comfortable armchair, the lights dimmed, I read these lines and think how this would be one of the three wishes I’d make if I had a golden fish. I’d create a museum that honors the complex history of its building while allowing artists and artworks to breathe freely — to exist within their institutional context yet remain true to their time and story. At one point, it struck me that this idea carries a broader meaning, as if it also speaks to how we ourselves choose what to preserve and what to let fade in the spaces we call our own.

Today, the Fondation Cartier shows that the brand no longer belongs solely to the world of luxury but also to the world of museology. Its objects, once made for personal pleasure and private collections, now become museum pieces — testimonies to the history of taste, craftsmanship, and social change. In this way, Cartier crosses the boundary between fashion, luxury, and the museum realm — between an object of desire and an object of study. In the context of contemporary art, that transition feels almost symbolic: what was once created to adorn the body now adorns the space of memory.

As I close the tabs with images of the exhibition and renderings of the new building, I realize that Cartier has become something of a mental totem — not because of the diamonds, but because of its mastery of storytelling. Perhaps that’s why the Toussaint necklace still holds such sentimental value for me, as if I’d worn it myself. I no longer associate it solely with that iconic film, but rather with a return to something that can neither be stolen nor lost — the quiet certainty that beauty exists.