I’m inclined to believe that, of all forms of human expression, film is the closest to magic. It can seduce, enchant, transport us to another reality, and reveal new worlds. Yet it can also serve as a litmus test for the world we live in. It can expose painful truths, touch the raw nerves of society, mark uncharted territories, and challenge or provoke reflection. In his text Before the Subjective Mirror: I Play a Member of the Generation, Makavejev pointed out that a “phenomenon can have as many faces as there are eyes observing it. I didn’t say half as many, because each of us can have more than two eyes — a skeptical eye, an optimistic eye, a tearful one, whether from sadness and disappointment or from joy. It’s all very, very complicated.”

All those eyes are film — thousands upon thousands of them, including those of the Black Wave. That short yet fruitful period opened each of these eyes to reality without fear of showing what they saw. Ethically, politically, and aesthetically daring and progressive, this period is likely the most valuable cinematic legacy our region possesses, reminding us who we are and what we are capable of when we forget.

So, “before the subjective mirror,” we returned decades back to the legendary titles of this era, from Feather Gatherers to Monday or Tuesday. We revisited them not to indulge in nostalgia, but to think forward more critically and remember that the role of art is to awaken us from stagnation, self-contempt, complacency, and even self-sabotage. The films of the Black Wave are bold, experimental, alive, furious, erotic, political, brutal, and deeply human. At a time when culture is once again under the pressure of repressive and regressive politics, it’s worth remembering that film is not an escape, but resistance. The new generation of actors — Hana Selimović, Andrija Kuzmanović, Judita Franković Brdar, Slaven Došlo, Matej Zemljič, and Jovana Stojiljković — stepped into the roles of protagonists from the Black Wave films. We spoke with them about the state of society and culture, the social engagement of cinema, artistic conditions, the meaning of creative courage today, and why, despite everything, film remains magical.

“Therefore, everything that happens to us, good or bad, serves us. Every disaster, if you’re creative and fail to turn it to your advantage in your next move, is your own failure. So no one has the right to cry about losing their bread or being screwed over. That’s how it is in film. You carry the fire you once swallowed. That fire should shine in your next film and become a sun. If it doesn’t, well — too bad. Then you get an ulcer. That’s also fire, only psychosomatic, and then you die and melt away.”

Dušan Makavejev, recorded by Živojin Pavlović, Belina sutra, Prosveta, Belgrade, 1983, p. 369

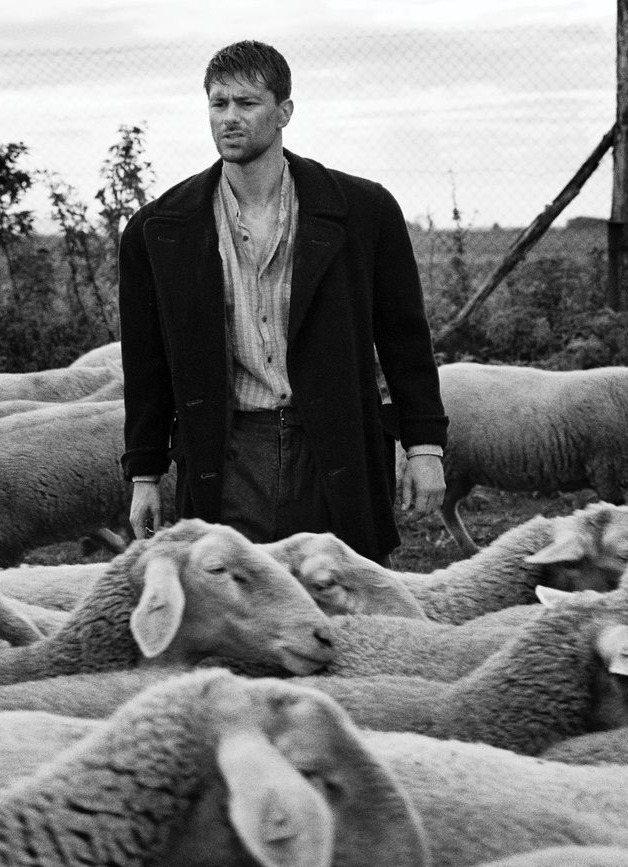

Judita: I wasn’t there when you were filming — it looked like you were having way too much fun! How did it go with the sheep? (laughs)

Matej: It was great! Fast, professional, simple. But the sheep were tricky. They weren’t as cooperative as we expected, but the photos turned out well. We should’ve filmed some behind-the-scenes footage with the sheep, it would’ve been hilarious!

Judita: I don’t know if you know, but we also filmed with sheep once — that short film with Sonja Prosenc.

Matej: I saw it! It was great.

Judita: Yes, and we had a whole flock there. They really don’t care — what you manage to catch is what you get. My cat wasn’t very cooperative either. They always say: “Never work with animals or children,” it’s like an unspoken rule, and yet both of us got animals. That’s probably why they paired us — we like challenges (laughs).

Matej: Actually, there’s another connection between us. We both won awards in Portorož. I got one for Consequences for Best Actor, and you for Erased for Best Actress. We’re linked in all sorts of ways, and yet we’ve never met in person.

Judita: Oh yes, I remember that so well. That year I went to Portorož practically alone — only Marko came with me — and your whole team was amazing. My crew couldn’t make it, so it was this total contrast between me sitting there solo and you guys cheering each other on. Such a great team, Temporama production — I later worked with them on Ida Who Sang So Badly Even the Dead Rose Up and Joined Her in Song, a film by the wonderful young director Ester Ivakić. They’re so nice, such a lovely production. Young producers, very cool people.

Matej: Both of our films did really well that year. That was 2018, but it feels like much longer ago — anything before the pandemic feels like another lifetime (laughs). Anyway, I watched your film afterward and you were fantastic in it.

Love Affair, or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator (1967), directed by Dušan Makavejev, is, alongside WR: Mysteries of the Organism, one of the most significant works of the Yugoslav Black Wave movement and a reflection of the sexual revolution within the cinema of that era. Like many other films from the Black Wave, it exposes the darker sides of life in socialist Yugoslavia, exploring themes of sex, violence, and death, while blending fiction and documentary footage.

Judita: Yes, that was the film Erased by Miha Mazzini, and Frljić also did a play on the same topic. It’s a Slovenian story — when Slovenia separated from Yugoslavia, there were many mixed marriages, and people had to register. But that information came out slowly, bit by bit, and if you didn’t register within the set deadline, you could literally show up at a government office and they would cross out your ID. There were even people in our film crew who had been among those “crossed out.” There were terrible stories; for instance, neighbors would find out that someone living next door was “erased,” so they would change the locks and take over the apartment because officially, you no longer belonged to that country. You couldn’t do anything, because if you showed up, they’d deport you. So people lived off the grid. There were so many awful stories. Anyway, Matej, are you working on something now or taking a break?

Matej: I’m taking a few days off right now, but otherwise, I perform in nine theater productions across Slovenia that are still running.

Judita: Do you have a permanent position anywhere?

Matej: Not anymore. I spent a few years in a city theater, but then I decided to quit and become a freelancer — and I feel great about it.

Judita: Is that harder or easier for you?

Matej: Most Slovenian actors would prefer a steady paycheck and a permanent ensemble, but I feel better this way. I work a lot, but I feel freer. It’s more interesting to collaborate with different people and companies — it helps me grow as an actor.

Judita: And you get to choose more, yes. I love that you said that, because it’s rare for someone to choose that path. I’ve been freelance my whole life too. I was never part of an ensemble. It’s very similar here — there are a lot of actors in Zagreb, Osijek, Rijeka, Split, and even private academies, so I understand that desire to belong to a theater. But I never wanted to be permanently employed. When people hear that, they tend to feel a bit sorry for you (laughs), like, “But you’re a good actress, don’t people call you?” And I’m like, I don’t want them to. Of course, that freedom is partly theoretical, but I feel I have more room to maneuver, and that keeps me alert. I also think actors in ensembles respond well when someone from outside comes in. We bring each other new energy.

Matej: Yes, it’s healthy, I agree. Still, people act like you’re a bit pathetic when you don’t have “your” theater (laughs), saying, “Don’t worry, it’ll happen.” Many don’t understand it. Since I started freelancing, I’ve taken a broader view of my work. I don’t see it as only theater, film, and TV, I do other things too. I teach, host events, run workshops. At first, it was terrifying, but I told myself I had to step out of my comfort zone. New opportunities started to appear, and I think embracing that made me a better person and actor. What about you, are you working on something now?

Judita: It’s great to take time for yourself. Even when I was younger, I wasn’t the greedy type; I always knew how to take a break and not accept everything. I never saw those pauses as dramatic, but as time to work on myself. During the pandemic, that was actually great for me. Before that, I worked a lot, and suddenly — stop. You read, cook, do yoga. And then, when everything started piling up again afterward, I was working intensely. I’d never had projects booked two years in advance, but then I did, and last October I realized I was so tense and had nothing left to give. Amazing projects were coming my way, but I turned down everything new. I simply couldn’t. I kept telling myself, “I need to recharge,” but in fact, I needed to empty out after so much stimulation. You have to know when to take time for yourself, nothing’s going to fall apart.

Matej: I agree. At the moment, I don’t have any new projects. I’m supposed to be working on a TV series, but for now I’m focused on the nine plays I’m performing in. In October, I had thirty shows, there were even days when I performed three times in one day, which was a lot (laughs). But I’m already in talks for next year.

Three (1965), directed by Aleksandar Saša Petrović, is structured as a triptych — three stories set at the beginning, middle, and end of World War II — following Miloš as he confronts the absurdity of death and the weight of moral dilemmas. In 1966, the film was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Checked long-sleeve shirt, cotton trousers, leather belt, and wool coat, from the costume designer’s archive.

Judita: It’s essential to take a break sometimes. Many people say, “It’s a job,” and I get that, it is a job — but not the kind where you’re burned out and keep pushing anyway. It should be a two-way street of energy, creativity, and ideas.

Matej: Do you ever get that fear of saying “no” to a project? That if you turn something down, nothing new will come along, and everyone will forget about you? (laughs)

Judita: I do turn down projects. If I feel it’s not right, it probably isn’t. I’m intuitive, and that’s what saves me. But I notice that young people today are often afraid of that — afraid to say no. It’s something they need to work on, because it’s a real obstacle. When you let fear guide you, you start calculating, and if that’s the case, you’d better be skilled enough to make those calculations work in your favor. Otherwise, the disappointment will hit harder. But if you don’t calculate, if you go into something with a clear heart, you just do it and see what happens. Most of the time, it turns out fine, and new opportunities appear.

Matej: I see our work and life in the same way — through energy. If you’re on a calm wavelength and know why you want or don’t want something, opportunities naturally come your way. It’s happened to me many times — when I was at peace with myself, good things came, and I had choices. When I acted out of fear, nothing worked. We shouldn’t be obsessed with projects, either. In Ljubljana, it’s funny because whenever you run into someone from our industry, the first thing they ask is, “What are you working on?” not “How are you?” (laughs). And if you say “nothing,” it’s like the end of the world.

Judita: You’re right, I used to test that too.

Matej: I’m most creative when I have so much free time I don’t know what to do with myself — that’s when ideas and new approaches come. I think in our profession, it’s necessary to postpone things sometimes so we can bring new characters to life. How do you see the situation for young actors in Croatia?

Judita: The dolce far niente philosophy… As for opportunities, what I’ve noticed is that it all comes down to you. It’s hard to accept because it means you’re the one responsible — but that’s how it is. Personally, what I love about acting is that I can grow through it. There are roles I could “ride” my whole life, but that never interested me. Acting always appealed to me because I could dig into something deeper. At one point, I felt like you reach a ceiling very quickly. You do something well, and people immediately call you to do the same thing again. That’s always been a turn-off for me — unless it’s a role I can expand on. My first role was in a teen series called When the Bell Rings. I played someone totally unlike me — a spoiled rich girl who wants to be a TV host or actress or singer — and it was so much fun. After that, a wave of terrible sitcoms hit Croatia, and they offered me a beauty queen role, but I said no. They told me, “Who do you think you are, turning down roles? No one will hire you again.” That was the moment I realized how quickly you can hit that ceiling. I understand why actors fall into apathy, which is why it’s important not to let yourself sink into that. These are tough times, and you do ask yourself why not just make money doing anything. I completely understand that, but I try to protect myself. I’ve been frustrated at times, and that’s fine for a while, but it doesn’t lead anywhere. You can also choose to change things, to start something. I realized I like going back to basics — pure theater, two chairs, and the actor’s craft. I started an independent arts organization with my colleague Vlatka Vorkapić, and the play I’m working on now is exactly that: minimal set, minimal costumes, just the story.

Matej: Honestly, it’s hard for me to talk about Ljubljana knowing what it’s like, for example, here in Belgrade — how difficult the situation is and how many challenges our colleagues face.

In Ljubljana, there’s a lot of work — many productions and shoots — but that doesn’t mean we should be satisfied just because things are worse elsewhere. You need to be resourceful, and it’s great if you’re interested in more than one thing. It’s hard to live off theater alone, and there’s no shame in exploring different paths. I choose to experiment, and that allows me to live with dignity. I’d always choose theater and film work, but it’s difficult everywhere because fees simply don’t match the times we live in.

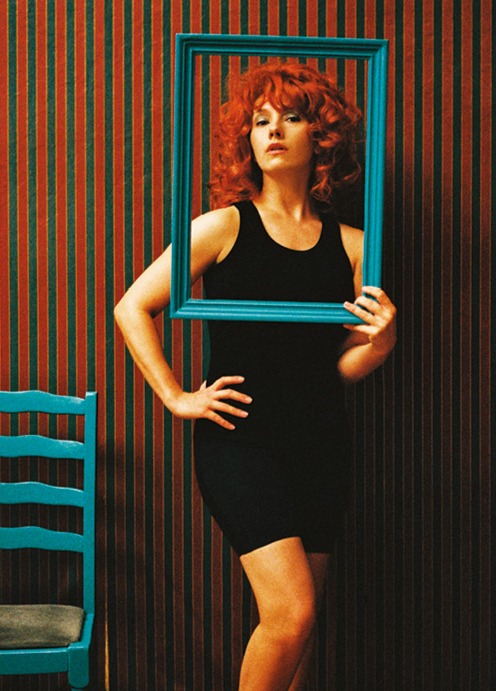

Dance in the Rain (1961), directed by Boštjan Hladnik, features Judita Franković Brdar in the role of Maruša, an actress trying to navigate her career and her complicated relationship with her partner Peter. Dance in the Rain is considered one of the first films that marked the beginning of the Yugoslav New Wave in cinema. Judita wears a tulle shirt and skirt, styled with a tweed crop top and shorts, and patent leather high-heeled shoes by Chanel.

Dance in the Rain (1961), directed by Boštjan Hladnik, features Judita Franković Brdar in the role of Maruša, an actress trying to navigate her career and her complicated relationship with her partner Peter. Dance in the Rain is considered one of the first films that marked the beginning of the Yugoslav New Wave in cinema. Judita wears a tulle shirt and skirt, styled with a tweed crop top and shorts, and patent leather high-heeled shoes by Chanel.

Judita: These are difficult times, honestly, and I don’t really know how to function in them. I’ve realized I’m more the type of person who expresses what I believes in through actions. I’m not loud, but I’ve felt a sense of responsibility for certain things and wasn’t sure what to do with it. Then I understood that I have a different way of showing the values I believe in. And I do believe that an individual can make a difference. You just take on something and do it — maybe it will inspire someone else.

Matej: I agree. I’m really happy about everything happening in Ljubljana right now, and I’m very proud of my colleagues. We have amazing actors and directors, and I’m extremely proud of Slovenian theater.

Judita: We’re lucky to make a living from our work, and it’s important to remember that sometimes. I’m really glad we worked on this project now, and the whole idea of Vogue Adria — it brought our regions together again. It created an opportunity for us to reconnect. We’ve become a bit divided, and that’s fine, but we should get to know each other again. I’m not romanticizing anything, we need to look toward the future, but the foundation we have is excellent — like the Black Wave and that legacy. The Black Wave brought freedom of expression; oppressive circumstances tend to produce extraordinary things. People are fighters, and that’s where our responsibility lies — in promoting ideas of unity and freedom. The global situation is terrible, but I hope resistance can emerge from it, and with it, new creativity. It’s all going to be okay.

Matej: I think what you said is very important because we’re living in hard times, and that’s why I believe this project matters so much. The Black Wave reminds us that in art, we shouldn’t seek comfort but truth. It’s proof that art can serve as a moral compass for society.

Monday or Tuesday (1966), directed by Vatroslav Mimica, explores the inner life of an individual, the flow of consciousness, dreams, and subconscious thoughts. Mimica used both black-and-white and color cinematography to portray this psychological depth, demonstrating the artistic courage and experimental spirit characteristic of Black Wave filmmakers. Cotton sailor suit and cap, tie, and leather shoes, from the costume designer’s archive.

Talent: Hana Selimović, Jovana Stojiljković, Judita Franković Brdar, Slaven Došlo, Andrija Kuzmanović, Matej Zemljič

Costume: Suna Kažić

Makeup: Irena Miletić

Hair: Milena Maršić

Set Design: Sandra Subić

Set Decoration: Vitomir Kovačević

Production: Teona Milićević, Marita Bobelj

Assistant Photographer: Darko Sretić

Costume and Fashion Assistant: Anastasija Jovanović

Makeup Assistant: Nemanja Radočaj

Lighting: Etar Film

Special thanks to the restaurant Tri šešira, Maša, Steva and Stela, as well as Milošević Sheep Farm.