Photographer Ivana Vareško fell for Kyrgyzstan and for Vogue Adria she shares why

"Between endless mountains and vast valleys, Kyrgyzstan is a country where nature still dictates the rhythm of life."

Ivana VareškoOctober 16, 2025

"Between endless mountains and vast valleys, Kyrgyzstan is a country where nature still dictates the rhythm of life."

Ivana VareškoOctober 16, 2025

There are places that follow you for years, quietly, almost without you realising it — they appear in books, films, photographs — places you dream about visiting but somehow never do. Kyrgyzstan was one of those places for me. On the map, it looks like just another dot in Central Asia, but it’s a land whose mountain ranges – the Celestial Mountains – connect Pamir, Himalayas, and Hindu Kush. This is a country that is rarely low – more than ninety percent of it lies above a thousand meters, and three peaks rise beyond seven thousand. Some say it’s the most beautiful mountain country in the world, though for me, Patagonia still holds first place and won’t be dethroned anytime soon. Still, Kyrgyzstan is easily in the top five.

The drive from the airport to Bishkek was enough to realise how wild this country still is. Horses, cows, sheep, and goats line next to the roads — every meadow is alive. Animals cross wherever they please, and no one seems to mind. The roads, on the other hand, are full of holes and fearless drivers. Steering wheels are sometimes on the left, sometimes on the right, people drive left, right but mostly in the middle — rules either don’t exist, or no one cares about them.

We landed in peak season, and there wasn’t a single car left in the entire country. Literally — not one. We sat by a fountain, opened Google, and started searching. After countless calls, a random WhatsApp message finally popped up: “I have a car.” Half an hour later, we found ourselves in some random neighbourhood. A guy stood in the middle of the street next to a car, waiting for us. Josipa’s first question: “Do you have an office?” He pointed toward a half-collapsed house with peeling wallpaper inside — that was the “office.” When we started the car, the screen flashed “Maintenance required.” He just smiled and said, “It’s okay.” We were worried for about three minutes, and then it became funny — after all, we had just rented a car via WhatsApp. We realised it might be smart to know how to change a tire, so while we still had signal, we screen-recorded a YouTube tutorial — just in case. Internet in Kyrgyzstan mostly exists in theory; outside the cities, you’re on your own. Google Maps and Maps.me rarely work. There’s a local app you can use, but even that one doesn’t update collapsed bridges, flooded roads, or the occasional landslide — all part of everyday life here.

After that little — let’s not call it drama, rather a story worth retelling — we headed south. On both sides of the road, scenes straight out of an old Yugoslav movie: Lada and Zastava cars parked by the roadside, families on those blankets every Yugoslav household once owned, eating lunch in the dust. Kyrgyzstan is a paradise for those longing for the old times — raw, unpolished, unapologetically itself. Forget America and its national parks — Kyrgyzstan has them all packed into one country. You drive along a road where white peaks rise on one side and terracotta canyons open on the other. The landscapes shift by the hour: in five hours of driving, you feel like you’ve crossed ten American parks, from Sedona to Yosemite. The Americans, as with everything else, just knew how to brand and sell nature— while here, nature remains wild, untouched, and blessedly free of queues to stare into a hole in the ground.

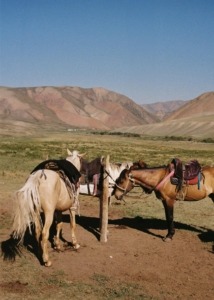

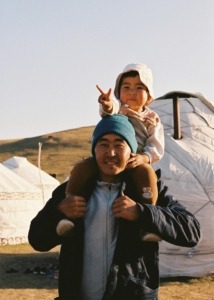

One of the most beautiful experiences of all my travels was a three-day horseback trek to Lake Son Kul, perched over three thousand meters above sea level. In summer, Kyrgyz nomads live around the lake in yurts. We stayed with one family — no electricity, no signal, water from the stream, food cooked over fire. The children, rosy-cheeked and always smiling, played ortotok with us — their version of dodgeball. No common language, just laughter. Beyond three yurts, there was nothing — only the lake, hundreds of horses and cows, and a silence I didn’t know existed.

After five hours of riding each day, the ground itself felt sacred. By the last day, I finally understood what “three days on horseback” really means. What I thought would be gentle rides across fields turned into a real adventure — steep rocky climbs above cliffs. When Ana’s horse fell to its knees mid-ascent, Kalys just repeated calmly, “Okay, okay.” That, along with left and right, was all the English he knew. In Kyrgyzstan, no one really speaks English, but everyone speaks Russian — so we actually got further with Croatian than English. Except when Ana tried to order coffee with cow’s milk in Bishkek and ended up mooing: “Moo moo.”

After the mountains and the time spent with nomads, returning to the cities felt like switching frequencies. Life pulses in the streets — children playing, old men sitting on benches, bread baking by the roadside, sold in plastic bags, several loaves at a time. On long drives, we’d often pull over for warm bread, fresh cream, and fruit — eaten in our laps, crumbs everywhere. In that car, everything was possible. Then again, we did rent it over WhatsApp.

On the road, I read a book about Kyrgyzstan, and among all the stories, one struck me most — the tradition of bride kidnapping, where women are taken against their will to marry men they’ve never met. The practice is illegal today, but in some villages, it still happens. We stayed one night with a mother and daughter. The daughter told us how her grandmother had been kidnapped at fifteen, escaped her husband, and was disowned by her family. Pregnant and determined, she finished university in Bishkek and later built an entire housing complex in Naryn. Today, her daughter and granddaughter rent out two rooms in their apartment to travelers. Though inspiring, stories like this are rare — the others, where women remain trapped in lives they never chose, are far more common. It’s hard to reconcile such brutality with the serenity of this place — with its endless mountains, quiet valleys, and stillness that feels sacred. Kyrgyzstan is a country of contrasts in the truest sense — wild and gentle, magnificent and, at times, brutal.

We felt those contrasts too — the family by the lake was kind and warm, the women in the guesthouse generous, but in one yurt, the owner, an older man, got into a physical fight with female guests. That aggression still lingers there, perhaps explaining why such traditions, however barbaric, continue to survive. Kyrgyzstan is breathtaking and raw — but it’s not for everyone. It’s not a country of luxury or spectacle. It’s dirty, it smells, showers and toilets are a privilege. Accommodation ranges from beds to floors, and nights in yurts can be freezing — layers don’t always help. The weather is unpredictable, extremes are the norm. But that rawness is what makes it real — everything here is honest, unmasked.

There aren’t many places in the world where you can sit in the middle of nowhere and feel you need nothing more. For me, that place was the valley by Lake Son Kul — the silence, the sky, and that quiet certainty that, even far from everything, you’re exactly where you’re meant to be.

Photo: Ivana Vareško