LOVE. HATE. FORGIVENESS. These three words close the circle of the complex relationship between Marina Abramović and Ulay — and the same can be said for the exhibition opening this November in Ljubljana.

A few years ago, one September, I bought Srećko Horvat’s book The Radicality of Love. On the first page, I left myself a dedication: You’ve left the stain on every single hour, all the treasures I find will vanish with the tide — a lyric from a song I had on repeat at the time. Besides the fact that this line clearly seemed fitting for the book’s title, knowing my romantic nature, I’m convinced it also had to do with a particular person I then believed had left a deep mark on me — though today, I can’t for the life of me remember who that person was. I’m not sure whether that’s funny, endearing, or a little sad, but from a certain temporal distance, most great loves don’t really seem that great. Still, what is evident is that the twenty-five-year-old me believed that the radicality of love existed solely in the extremes — between someone’s absolute presence and their complete absence. The thirty-three-year-old me agrees that it is indeed a brutal face of love, but she’s also learned that love, by its very nature, is radical enough.

Lately, I’m completely certain that to be loved means to be permanently changed — whether we’re ready for it or not — and in ways we can’t predict. It’s no wonder Horvat claims that if we were to place revolution in the context of relationships, it wouldn’t be a one-night stand, or a passing flirtation, or a situationship, but rather a true love so forceful that he often equates it with violence. Love is undoubtedly the most powerful force in the universe — transformative and “beautiful as revolution” — yet at the same time, it is violent and capricious. It doesn’t wait for you to be ready or to invite it in; it doesn’t care whether the timing is right, whether you can handle what it brings or what it takes away; it shows no concern for the state it leaves you in once it’s gone. It demands time, energy, attention — in short, love is quite the bully, and we surrender to it time and again, even though we know how it will end. Because once the Encounter happens, nothing else matters; like a small death, when Love is there, nothing else exists.

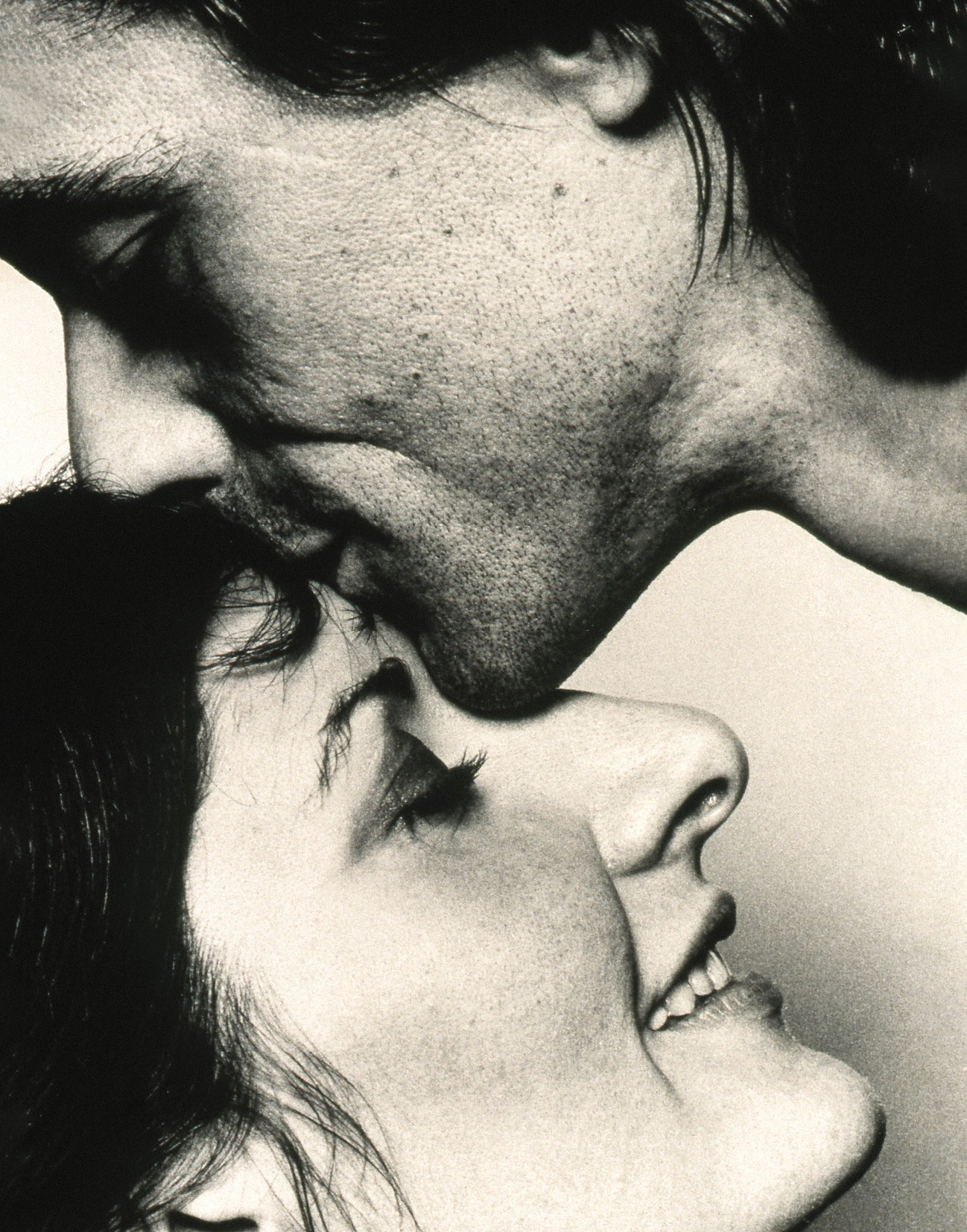

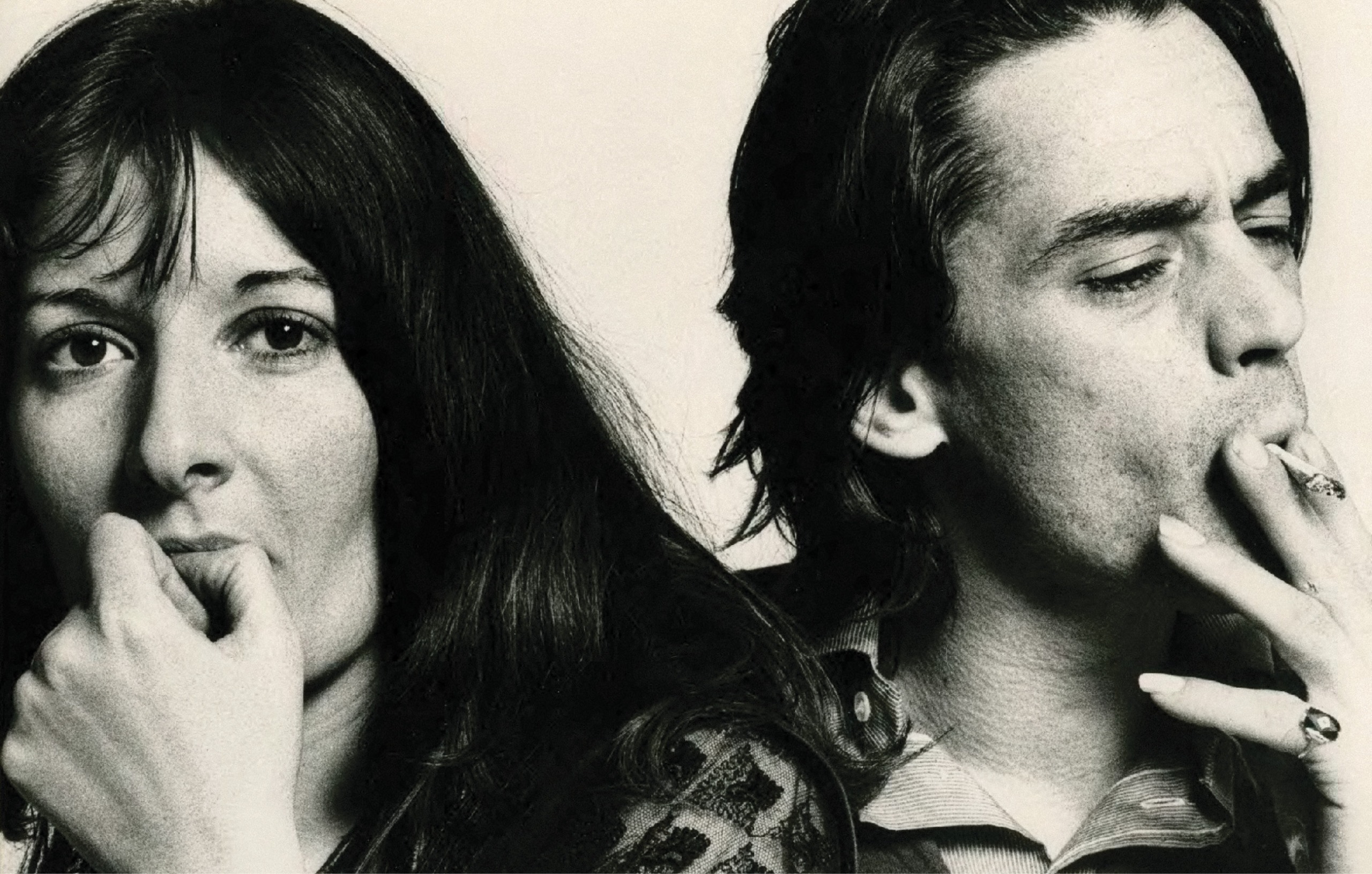

Such encounters don’t happen often, nor to everyone. Those of us who are somewhat lucky can hope that if we’ve missed (or ruined) one chance, we might be granted another; those less lucky may never experience it at all; and those most fortunate of all live a love story that becomes larger than themselves — one that enters legend. Among the latter, without a doubt, is the story of Marina Abramović and Ulay. You’d have to live under a rock not to be familiar with the complexity and depth of their relationship. This year, four years after Ulay’s death and nearly fifty since their first meeting — a span that encompassed love, cohabitation, a series of joint performances, an epic farewell on the Great Wall of China, years of silence, a reunion witnessed by millions both online and in person during Marina’s MoMA performance, and later, new cycles of debate, resentment, lawsuits, and finally reconciliation — a new chapter is opening, one even they couldn’t have foreseen. Partly because their shared manifesto Art Vital insists that there is no predicted end, and partly because any sort of reconciliation once seemed unimaginable. Yet their love and artistic partnership will find an unexpected epilogue in the exhibition ART VITAL — 12 Years of Ulay/Marina Abramović, opening on their shared birthday, November 30, at Cukrarna. The show is dedicated to their years together, their love, and their creative work — and marks the first time not only all their pieces but also their photographic archive will be displayed in one place.

Reflecting on my own great Encounter — where, even a year after parting ways, I’m still unsure whether such an important story begins from the start or from the end — and, truth be told, a bit nervous about speaking to the woman whose work gave meaning to my studies, I told Marina that I don’t know where to begin. How does one even begin to unpack the legend that is Ulay and Marina? From the beginning? “How many pages do we have? (laugh). There’s no need to go back to the beginning — everyone already knows how we met. Let’s go backward. I’d like to start with the book Lena and I did, Love. Hate. Forgiveness, which might be the thing I’m happiest about. My relationship with Ulay had every possible aspect of what a relationship can be: an incredible love story, separation, moments of absolute hatred, and finally, forgiveness. This exhibition is all of that. Four years after his death, I can say we probably never would have done this together, but I’m very glad Lena is involved. After all, she’s the one who brought us back together.”

I was never quite sure how it really unfolded, or whether they truly met for the first time in twenty-two years at Marina’s performance The Artist is Present, when was the moment when real, sincere reconciliation happened and where, then, the courtroom encounters fit in in this timeline. “That was indeed the first time we had contact after twenty-two years, but a lot of unpleasant things happened afterward. After that, after our trials and after I had lost everything, I went to a small, hidden Ayurveda hospital in India. I arrived after a thirty-six-hour flight, at six in the morning, completely exhausted, and he and Lena were already there. Pure coincidence. They didn’t know I was coming, no one did. They had chosen that place to rest, I had chosen it to forget the previous period of trials, which had been extremely stressful for me. When I saw them, I thought, ‘What the hell am I going to do?’ My first reaction was to leave. Ulay and I didn’t speak at all; we hated each other, and I was supposed to spend a month there. Then I began to think that there must be some reason why he was there, why I was there — some synchronicity, logic behind it, fate. How was it possible that we were in the same place at the same time? And that’s why I stayed. Lena deserves a lot of credit for creating the situation where we could start talking, and somehow we forgave each other. That’s why it’s so important to me that this is part of the conversation about the exhibition. Forgiveness is an incredibly beautiful word, but we use it lightly. Truly forgiving someone requires a lot; it’s very difficult.” Especially for someone of Montenegrin descent, I added, and I realized that, thanks to Marina’s incredible immediacy and directness, I had suddenly gone from being quite nervous to the complete opposite. “Exactly — especially for me. Montenegrins don’t forgive anyone (laughs). But this was really the moment when I forgave someone completely, and I felt in my heart that all the negative energy between us had disappeared, that we could be friends, truly heal from hatred, and move on with life.”

During the period when the idea for a joint exhibition emerged, Ulay was already ill and, although the desire existed, he did not have enough energy to pursue it. Still, Marina and he managed to film the documentary No Predicted End in 2018 about their relationship, and after Ulay’s death, his perspective on the story was brought in by his wife, Lena. She and Marina worked together to tell the story in the book Love. Hate. Forgiveness, which is dedicated to Ulay and concludes with a conversation between the two of them. “It was incredibly interesting to work with Lena because her view of Ulay does not at all coincide with mine. We were with two different versions of the same man we had both lived with. Our perceptions differ greatly, and she also had a very difficult role, investing a lot of her life and energy in caring for him. With this exhibition, I am closing an extremely important chapter. It represents twelve years of life that have never been shown in their entirety. Whenever I have an exhibition, I display something from that period, but I have been creating for sixty years now, and twelve years is only one period, one phase. Ulay worked the same way. So, to have just our works and archive, with a catalog and eleven writers analyzing our work from sociological, spiritual, artistic, and political perspectives, is incredible. This exhibition is extremely important to me, and that is why I don’t want to start from the beginning, but from forgiveness. That’s also why I don’t want to be photographed as ‘me’ — this isn’t just about me; it’s about Ulay and me. The only photograph that could appear on the cover is one of the two of us at the moment we met. That’s the only proper way.”

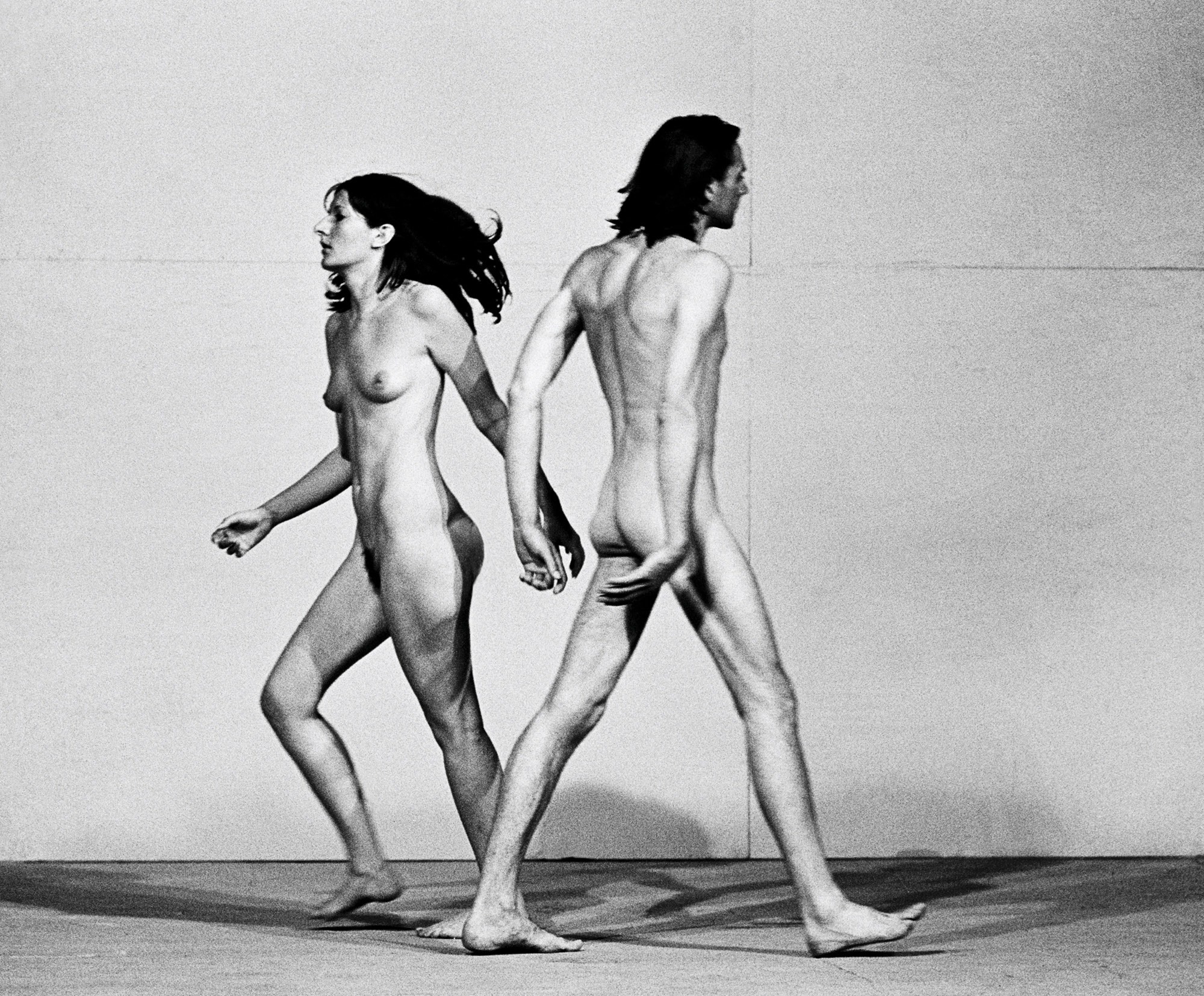

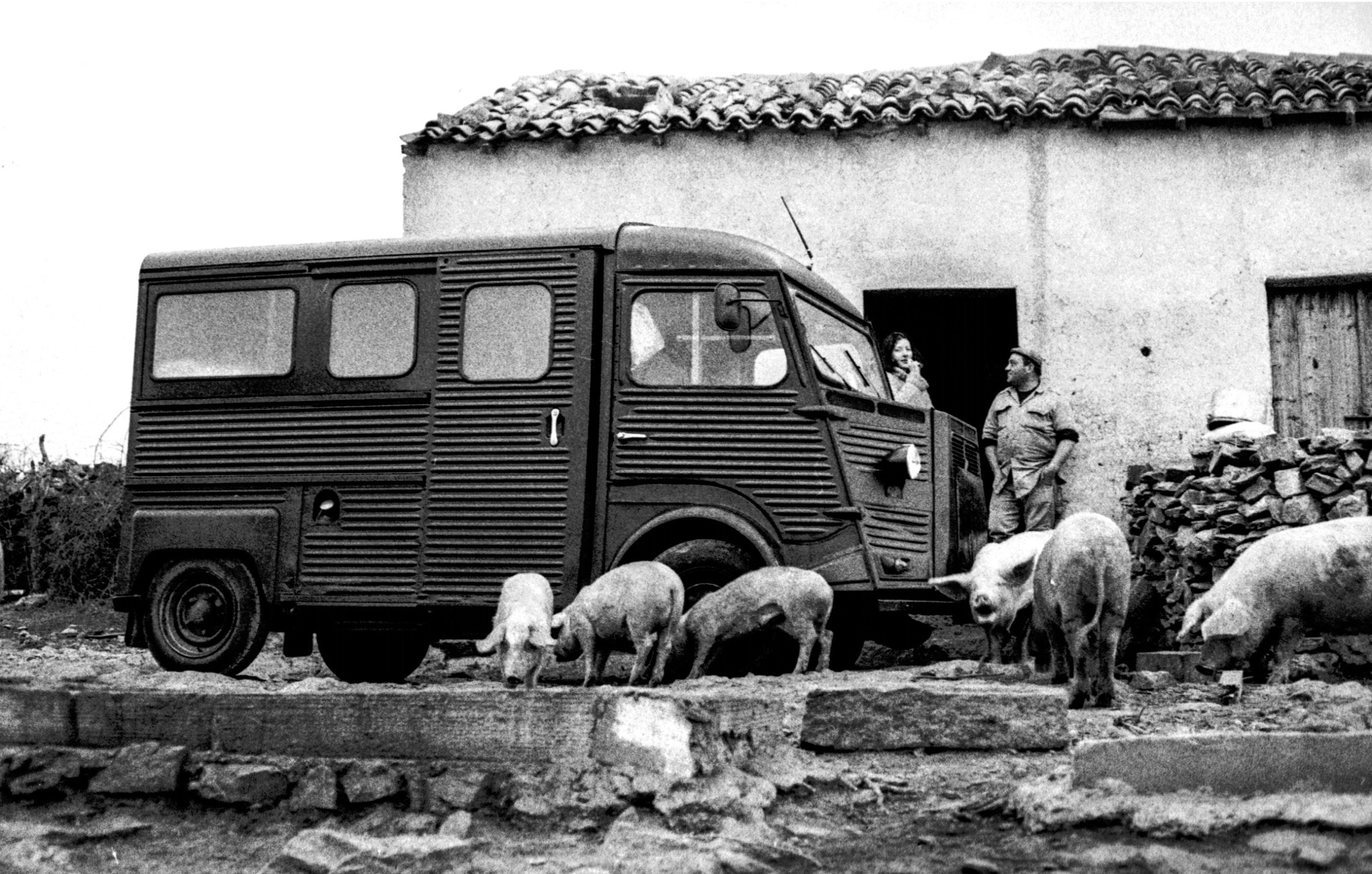

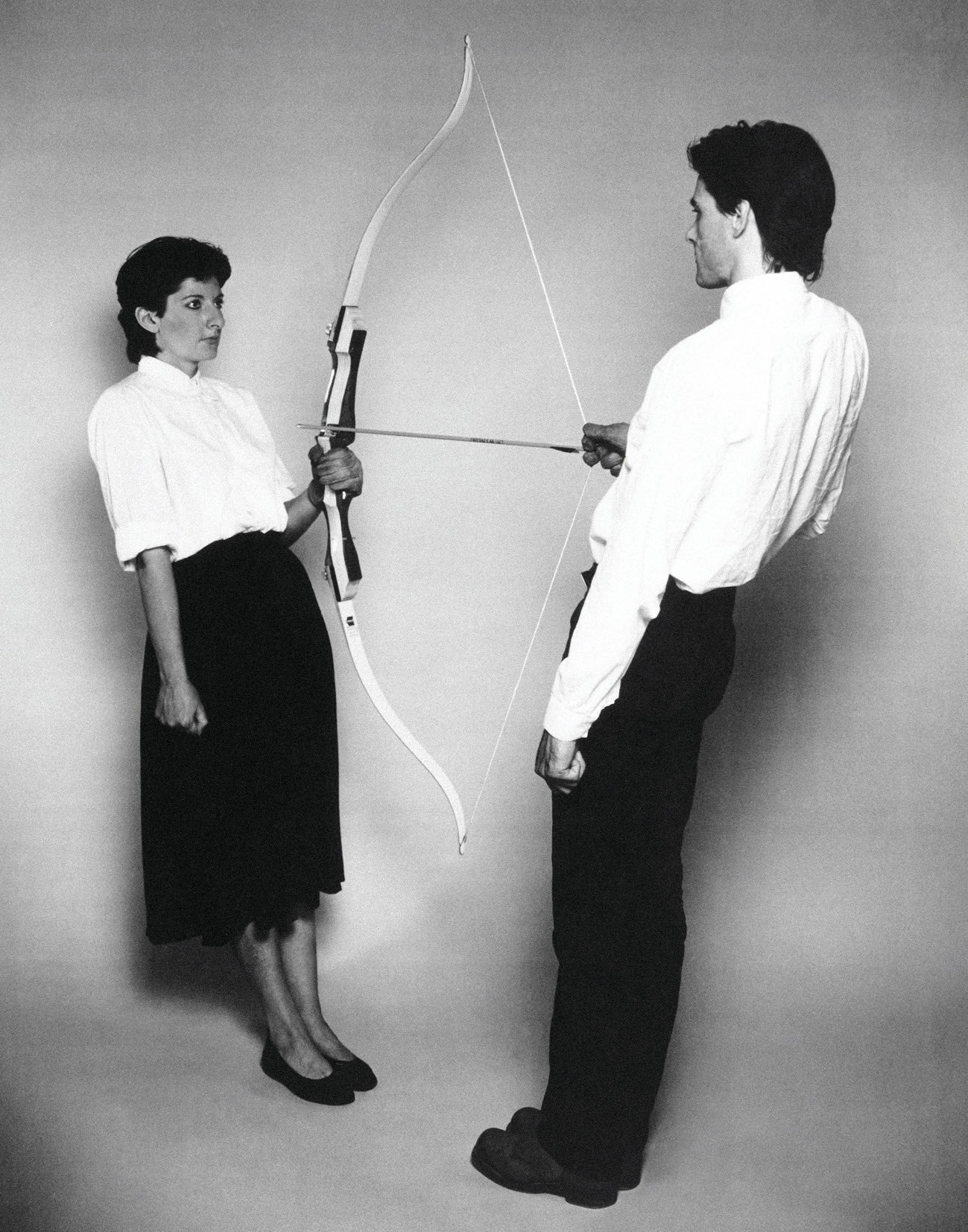

I nodded in agreement because I truly agree, and I promised that we wouldn’t go back to the beginning at all — yet it was impossible not to talk about works such as Imponderabilia, Relation in Time, Relation in Space, and Rest Energy, which not only marked their careers but also the history of contemporary art. About a period that may be just a small part of a bigger picture, but one that enriched both careers and deepened and intertwined their shared relationship to a level few could even imagine. Working together and loving each other — that is a very complicated thing. “The works of Ulay and Marina Abramović, the majority of which will be featured in the Art Vital exhibition, pushed boundaries, shocked audiences, and provoked wonder, disgust, surprise, anger, respect, and admiration. For five years, they lived in a van that served as their home on wheels, constantly moving, traveling, exploring, talking, creating, and living. Their nomadic spirit, immense energy, and the discovery of the connection between themselves and the world around them were the main driving forces behind their dedication to art. They were unstoppable; they were one. Simply put, for them, life was art, and art was life,” Alenka Gregorič, co-curator of the Art Vital exhibition, told me when I asked her to give me at least a glimpse of what she would write in the introductory text. “Exactly!” Marina nodded. “One of the reasons I forgave him, and he forgave me, is that we realized private life is one thing — and there’s a lot of nonsense in it — but our collaborative work is more important than that. We created that special chemistry, made performance history, and we cannot deny it. Only by doing so could we forget all that we invested of ourselves. I thought: ‘Enough with the nonsense, respect your work.’”

Yet reaching that phase is always difficult — to begin with, because every great love, like a revolution, demands that we give of ourselves fully. For incredible things to happen, one must surrender to them completely, and when the most beautiful and fruitful relationship reaches the point where everything becomes only hurt, with no way forward or back, it is hard to find balance. After a great love, usually nothing remains except returning to the starting point from which it all began — being strangers to each other. For Marina and Ulay, it was impossible both to stay together and to exist separately while somehow remaining connected. In 1983, Abramović and Ulay announced that they would create their final joint work, The Lovers. They would be the first people to walk across the Great Wall of China on foot and marry at the point where they meet. It took five years to obtain the necessary permits — and for the relationship to finally consume itself. They began their journey on March 30, 1988, starting from opposite ends of the Wall, also called the “Sleeping Dragon.” Abramović set out westward from the dragon’s head at the Bohai Sea, an extension of the Yellow Sea between China and the Korean Peninsula, while Ulay began at the dragon’s tail deep in the Gobi Desert. After ninety days of walking, they met, embraced, and parted ways. They returned to Amsterdam on separate flights, and after years of complete intertwining, twenty-two years of absolute silence followed. Anyone who has lived through that knows that while it is liberating, nothing is more frightening than a new beginning after such intensity. Reading about this work again and again, I always wondered: did she feel freedom or fear on the plane to Amsterdam? “Absolute fear,” Marina said. “I was frozen. There was nothing free or exciting for me. When we decided to live and work together, I was ready to do it for the rest of my life. I truly was. I imagined that we would exist forever. But life had other plans for each of us. We parted on the Great Wall, and afterwards, I sank into a deep depression. I was forty years old; all my performances had been done in pair under our joint name, and I was left simultaneously without my work and without the one I loved. It was terrifying. Normally, whenever something went wrong, I would turn to my work. But now I couldn’t, because I no longer had it. I had to devise a completely new approach. I realized that the audience was extremely important to me, and that’s how Transitory Objects began — a series of works inviting viewers to become active participants — and gradually, I returned to my performance practice. After many years, at MoMA, it all came together, and instead of Ulay, the audience was across from me.”

Precisely because of this intertwining, when speaking about their relationship and work, words like Alenka’s are often used: “They were unstoppable, they were one.” However, within that union lie the greatest dangers—both for the artist and for the individual—and the eternal question arises: how can one be both oneself and someone else’s at the same time? The people with whom we complement each other are recognized the moment they appear in our lives, yet it is not easy to find such a finely balanced shared language. How do you create together without endangering either yourself or the other? “It was very difficult. When we started working, we had that aura of the perfect couple who lives and works together. At that time, there were many couples doing the same, but after a few years, they would separate. At my age, only Gilbert & George are still working together. So, twelve years is quite a long time. We separated because of foolishness, jealousy, infidelity… But the question of how we worked together is very important. We truly combined the best of my work and his. You know, the fact that we were born on the same day is no coincidence. We share the same DNA in many ways, and one of the important things is how we control our egos. Every artist has an ego as big as a mountain, and we had to work on restraining it. We agreed never to say whose initial idea a performance came from, and neither of us ever revealed it, because our system was such that the idea would come, then we would refine, polish, and develop it together before presenting it. We called it ‘thatself’—it was neither mine nor his, it was something else. Once we established that, we created an alliance, a community. The other thing is, of course, Art Vital, the manifesto. We became modern nomads, constantly moving, doing different things because we couldn’t make a living from our art. It was hard, but at the same time, beautiful.”

In relationships where the professional and the emotional are so closely intertwined, once things go wrong, mental and emotional numbness borders on an inability to take any independent step. By sharing this experience, perhaps a little selfishly, I’m trying to feel my way toward an answer to a question that keeps returning to me: how much can we learn from someone’s absence? In the years of working on her own, what did she learn that she couldn’t have if her original idea—to work together forever—had come true? “When I finally stood on my own two feet, I think the first thing I decided was never again to do collaborative work with anyone (laughs). Occasionally it happened that I created something with someone—Igor Levit, Jan Fabre—but never again as the sole form of my work. That kind of trust I would never give to anyone again.” I couldn’t agree more. We seek love in every experience, believing it deeply that it will be enough, and yet it often leaves us tangled, dependent, pale, and afraid. Despite that, each time we encounter a new illusion we forget the pain. We live for death and resurrection. I couldn’t help but think of Seven Deaths of Maria Callas, which tells the story of Maria haunted by the seven operatic roles she performed throughout her life—La Traviata, Tosca, Madame Butterfly, Carmen, Otello, Lucia di Lammermoor, and Norma—and in every one the herioina dies for love. Love turns into hatred, hatred becomes love, and symbolic death becomes ultimate liberation. Maria was a woman whose life—and death—were marked by love, and in Seven Deaths death recurs endlessly. But is Maria Callas truly dead, or does she still lingers in all of us who suffer and oscillate on that thin edge, hoping for a new resurrection? “That’s really a great example. When Ulay and I broke up, I was in a very bad place—I was depressed and disappointed—but it wasn’t him who broke my heart. It was my next partner, my husband Paolo. I couldn’t sleep, I couldn’t eat, I just kept talking about it, my heart was completely shattered. It’s really an illness, it’s terrible. I wanted to make that opera about Maria Callas because she literally died of a broken heart in her apartment in Paris because of Onassis. She completely destroyed her career for him. In my case, my work saved me; in hers, sadly, it didn’t. That’s why I felt the need to do an homage to her. I show only the dying. It lasts just 1 hour and 36 minutes. The opera became incredibly successful and everyone insists I perform it again—but for me, once is enough. I will try everything once.”

As we talk, it seems to me that through the window behind her in northwest England, rain is beginning to fall, bringing me back to the reality that we are each drinking tea in our own rooms, two thousand kilometers apart, during a break as she prepares a new project premiering on October 9. How is it for her there? “Everywhere feels like home to me; every hotel is another home, because I truly believe that my home is my body, not the space you live in. It’s raining constantly, and the weather is terrible, but I’m working on the biggest project of my life—Balkan Erotic Epic, which draws on Balkan culture and pagan rituals. There are 120 people involved. It’s insanely large, and I work at a crazy pace every day. Balkan Erotic Epic begins with Tito’s funeral.” I laughed. “That’s not so far from an erotic experience,” I said, thinking of Horvat’s quote: “What mattered more was that sexual restraint provokes hysteria, which can be redirected into feverish belligerence and leader worship… All that marching, cheering, waving flags—it’s all repressed sex.” “ Exactly. When I was young, when all that happened, in my opinion, it was a very erotic experience. Tito’s death and funeral. Women were beating their chests and staring at the sky. Women in the streets, women in the villages. ‘Why did you take him and not me?’ they were really saying that. It’s funny what question they were asking—who did they address it to, who took him, God? We didn’t believe in that; we were communists. So all those elements of sexual energy and mourning for Tito found their place here.”

From a certain distance, we are not satisfied with some works, manage to revisit others and take them in new directions, and some we would rather forget. Just like loves. Balkan Erotic Epic reconstructs Marina’s work of the same name from 2005, just as Art Vital will reconstruct her and Ulay’s shared work and life. What does it look like today to go back almost fifty years, and how will she reconstruct her works this time? Seeing their reperformances at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade was a powerful and important experience, since reperformance is a new way of preserving, archiving, and even giving life to a work. “I think the same. If you’re just presenting an archive, it’s not enough. There has to be a living moment in the retrospective. At first, Ulay didn’t agree with it because he thought no one else could perform our performances. Later, when he saw how we train people and select excellent performers to present it in the best possible way, he supported the idea. You can have someone who plays Mozart completely off, or someone so brilliant it sounds like Mozart himself, but also brings their own charisma. The same goes for performers—great performers can add an entirely new layer to a work, enhancing it. So there will be people from my institute, mostly Slovenian artists. The performance has to live. In addition, there will be works that no one has ever seen. We had a piece made of bones and wire that we only showed once in Eindhoven. There will be our cars, in which we lived together. So much that the audience has never seen in one place—even I haven’t (laughs). I’m also happy to return to Ljubljana. I was there for the first time with Zdenka Badovinac, who at only 26 was the youngest director of the Museum of Modern Art. I love NSK, the OHO group, I love Žižek; generally, there’s so much good in Ljubljana. There are so many people from different ex-Yugoslav republics living there in peace.” I shared with her that I have a particular love for the city, and my lifelong fantasy that one day Slavoj Žižek and she would do a joint interview. Sometimes, when I don’t know what else to imagine, that image comes to mind. “I met him once, at the Slovenian Embassy in New York. We talked for less than seven minutes; he’s a genius. His brain works faster than he can speak, and he literally spits words at those who listen. It’s like an incredible performance of an incredible mind. He published two books about communist jokes—I have both. Humor is so important. To make sense of the horror of the world we live in, humor is a necessary tool, one that can save the world.” And art? Can it do anything useful?

“Art will save the world?” “That’s bullshit. Art has never saved the world in the past, and it won’t in the future. The only thing it can do is raise awareness about important issues, make people stop and ask themselves what we are doing, why we keep repeating the same mistakes, the same wars since the dawn of civilization. People have been killing each other all the time, from the beginning. Only if we manage to learn forgiveness—which we never do, something might change. That’s why perhaps one of my favorite interventions was the one I did at Glastonbury last year. In silence, 256,000 people were connected. It’s very risky, hard to perform, but I succeeded. Seeing so many people who don’t even know each other, connected by silence, understanding, and unconditional love in this terrible world, is something incredible.”

Silence has an incredible potential to heal. I witness that every time I stand surrounded by thousands of people at a protest, standing in silence. There is nothing more powerful than feeling someone’s presence and appreciating it in silence. To be silent together is probably the greatest measure of safety and love. “Serbian students are the heroes of today. You are going through hell, but they are persistent heroes.” I thanked her for publicly saying that and told her I hope we will see each other again after Ljubljana, under different circumstances. What are her plans in the meantime? “I hope so too. As for me, I truly believe that art is a mission. Next year I turn 80, and I wonder how much time I have to make everything I want. So everything I don’t want to do, I don’t do. Only what excites me. I don’t do stupid things. I’m currently developing an avatar; I want to see how I can connect better with young people, but I also want to see how it can help me slow down. My agenda is full until 2028, and that’s great. Life is a miracle, but you never know when it will end. So you have to work constantly. Something that guides me lately is: ‘let’s have more and more of less and less.’”

She left me with that sentence. I closed my laptop at the same moment the rain began to fall here as well, and I continued to sit for a while, captivated by the sheer magnitude of everything that had unfolded in our exchange. Exposed to that powerful energy intertwined with vulnerability, the strength that channeled the most emotional into work, the story of a relationship that marks for a lifetime, and the freedom and courage it requires, I felt throughout my body that a part of me—one I didn’t even known was waiting to be fed—had been nourished. Her love and openness to life, in which there is always so much more yet to happen and change, reminded me of one thing: “to be a true revolutionary, above all, you have to be a romantic”.

Foto: © ULAY / MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ. COURTESY OF THE MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ ARCHIVE