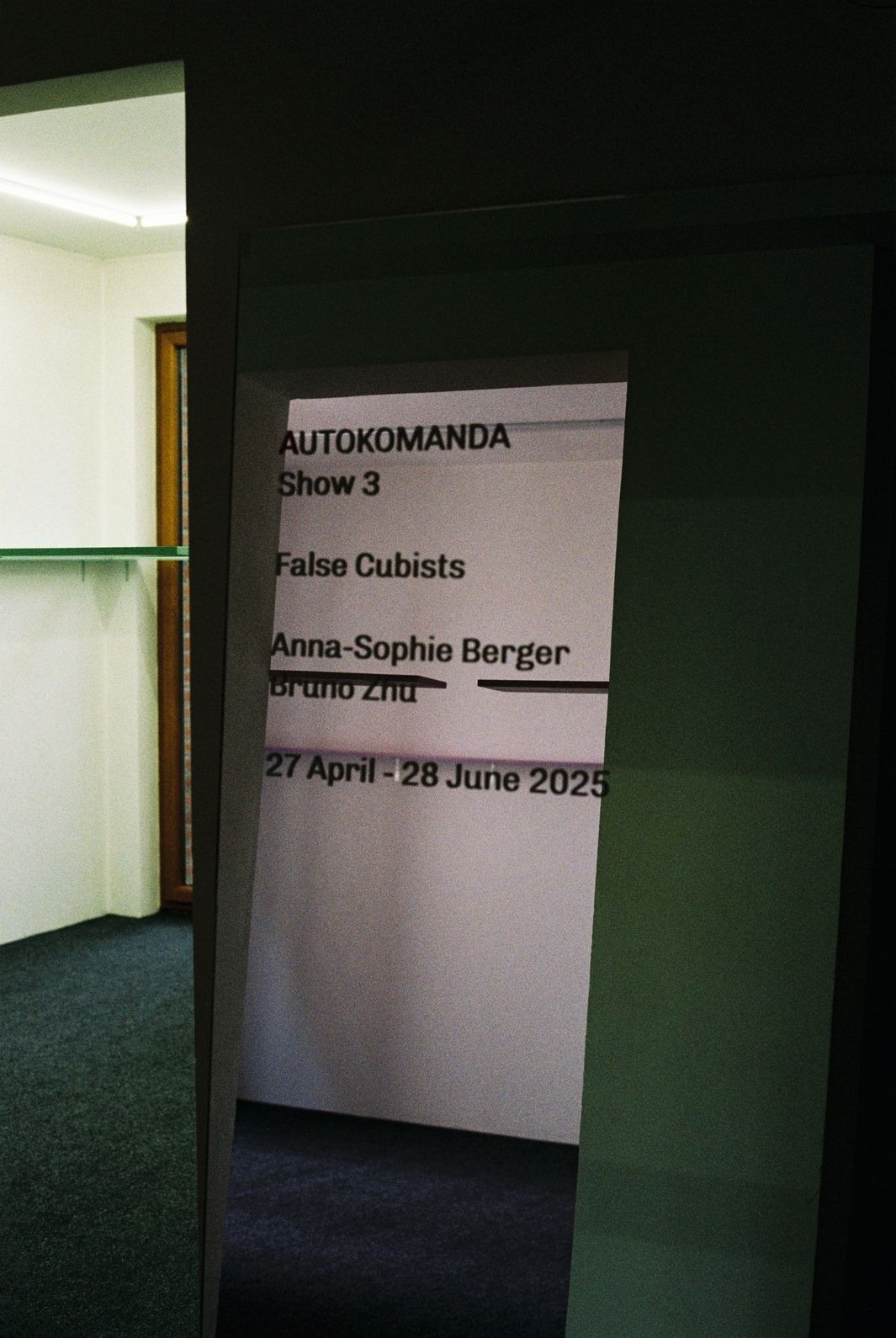

False Cubists in Belgrade raise questions about body standardization and symbols of power

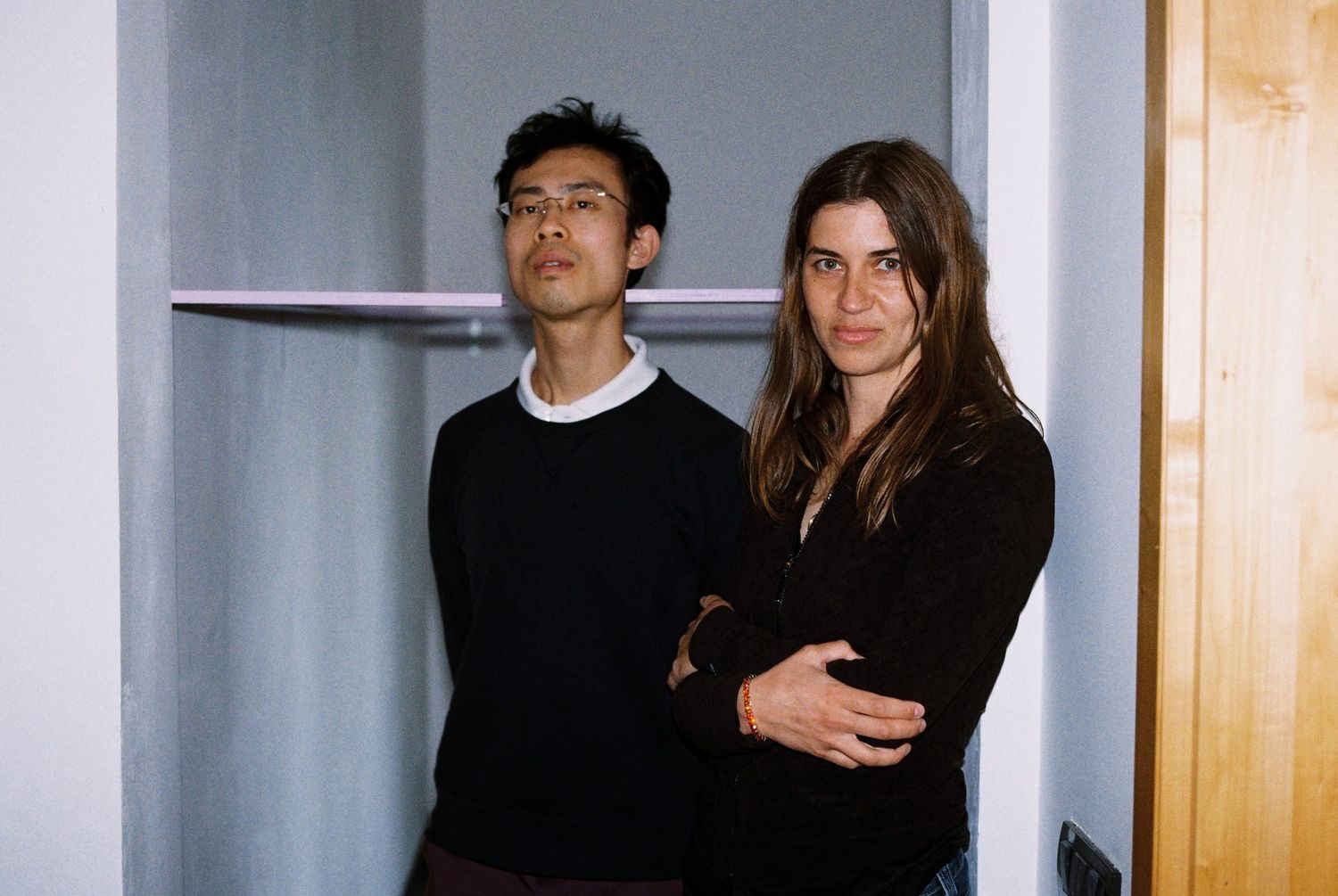

We spoke with artists Anna-Sophie Berger and Bruno Zhu about their new exhibition in Belgrade

Bojana JovanovićMay 7, 2025

We spoke with artists Anna-Sophie Berger and Bruno Zhu about their new exhibition in Belgrade

Bojana JovanovićMay 7, 2025

As I walked through the streets of the Vračar municipality (streets I clearly don’t frequent often, since at times I felt as if I were in another city) I noticed how, despite the traffic, they still preserve traces of urban greenery: tree canopies arching over sidewalks, cooling the concrete beneath them. They seem like rare remnants of care for space and the body in contemporary Belgrade. And right there, in that specific transition between the bustle of the city and an almost intimate atmosphere, lies the Autokomanda art space. A space that is unassuming yet determined in its mission to decentralize the city’s cultural scene and open up room for artistic practices that come from the margins—ones that may not be part of Belgrade’s dominant artistic narrative but successfully challenge and expand it.

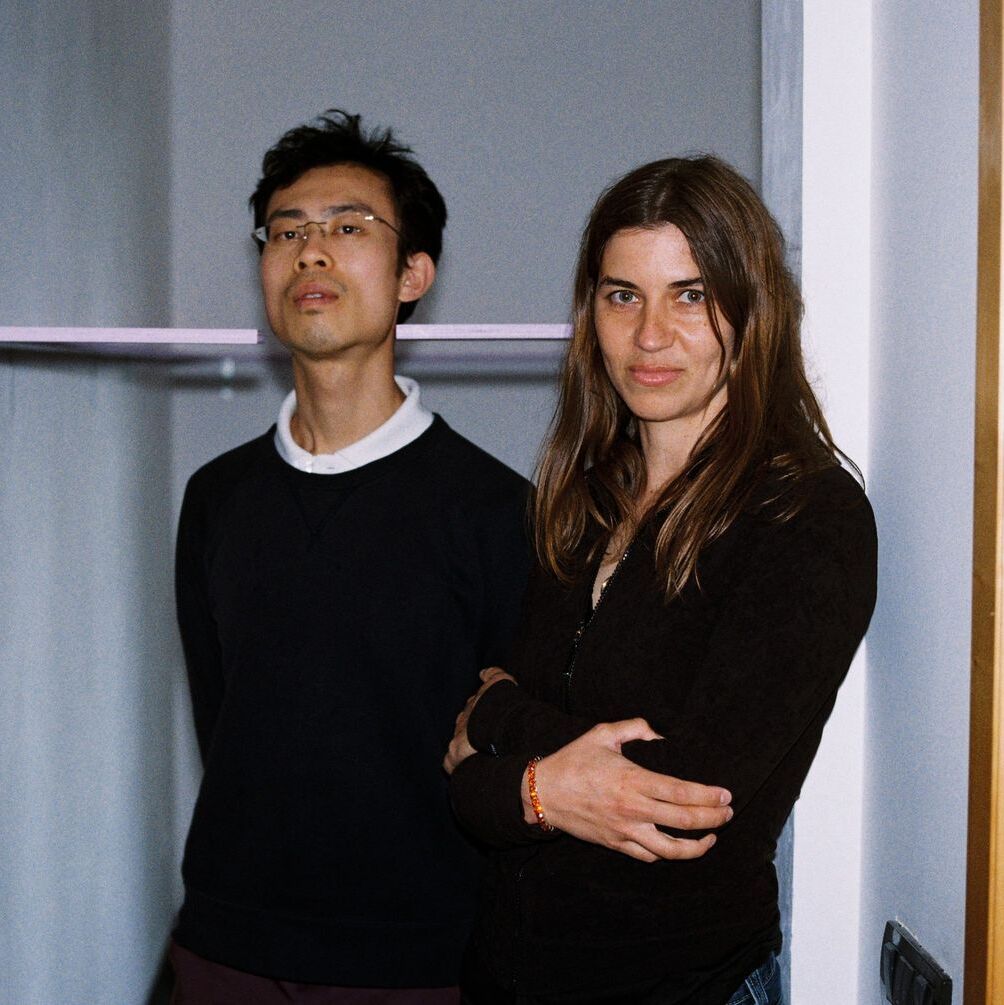

The conversation with artists Anna-Sophie Berger and Bruno Zhu mirrored the exhibition they created—thoughtful, layered, and at times restrained, yet charged with a deep tension between aesthetics and politics. Their work at the Autokomanda art space carries a title that is in itself provocative: False Cubists—immediately raising questions about authenticity, commercialization, and the institutional frameworks of art.

I first came across these two artists (on separate occasions and under different circumstances) nowhere else but on Instagram. Bruno popped up on my feed, and since I’ve recently been looking to refresh my digital journal, I enjoy following a wide variety of content and people from around the world. As for Anna—unsurprisingly—I discovered her in a similar way, only this time a friend sent me her work and asked if I had heard of her. Since then, I’ve been closely following the careers of both artists, and some of their works have particularly caught my attention. For example, Bruno’s I believe in you from 2024, which explores how audiences, filled with anxiety and unease, turn to the market to reshape their identity through clothing, signs, and attitudes. The installation examines dressing and addressing as interconnected political-aesthetic concepts, using a textile alphabet made up of sleeve-letters G, A, and Y, and a skirt shaped like an exclamation mark.

Anna’s project Don’t smoke from 2018, which is also referenced in the current exhibition in Belgrade, caught my eye with its compelling series of installations and symbols. The exhibition at the Emanuel Layr gallery in Vienna explored themes of national identity and consumer culture through a series of sculptural works. These pieces were named after European countries and made from materials such as plywood, fleece, thread, screws, and plastic wheels. These materials, often associated with mobility and transience, were used to create objects reminiscent of both furniture and luggage—suggesting a commentary on movement and the commodification of cultural identity.

So, you can imagine my surprise (and excitement) when I found out that these two artists are teaming up for a new project at the Autokomanda art space.

The exhibition is radically pared down: two massive forms installed at the entrances and along the walls of the gallery’s exhibition rooms resemble collars—almost industrial constructions, cold and precise—offering a physical experience to the visitor. This minimalism calls for contemplation; it’s not there to please the eye or offer a clear narrative, but to pose questions about the standardization of the body, normative measures of “human-ness,” and the symbols and power we wear—knowingly or not.

Precisely because of this stripped-down, almost architecturally precise clarity of the installation, the exhibition experience depends on the presence of the body—both the visitor’s and their gestures, hesitations, and reactions. As I watched other visitors, I noticed how the space transformed into something between a set design and a tool. People were constantly recording, entering and exiting, slipping their necks through the narrow openings of the structures, testing their own “fit” within the tightly defined dimensions of the work. This physical interaction—often driven by curiosity, and then by the urge to document—further highlights the tension of the work: what does it mean to be part of a system built to measure, but not to your measure? In that moment, the space becomes an experiment in normativity, where the audience unintentionally performs exactly what the work critiques.

The installation demands context but refuses to be explained. Its cold aesthetics and strict minimalism are not a lack but a method—one that provokes the question: what happens when an exhibition refuses to be comfortable? When it refuses to acknowledge the audience, and instead urges them to prove themselves, to claim a place that was never meant for them?

Starting with the idea of “False Cubists” — how did this term transform within your work? Was it more of an inspiration, a provocation, or something else entirely?

Anna: I stumbled upon the term “False Cubists” in Nancy Troy’s study “Couture Culture” (Nancy Troy: Couture Culture: A Study in Modern Art and Fashion. Mit Press, 2002). She looks at the shared strategies in the marketing of luxury goods in early twentieth century Parisian fashion houses such as Poiret and art galleries. She quotes the term “False Cubists” from Henry Kahnweiler, a seminal Parisian art dealer of the first generation of cubists such as Picasso or Braque. False Cubists according to him were those artists that chose to show their work publicly in salons while he advised his artists on making themselves rare as a means to secure their status.

When Bruno and I started to think about a collaborative project the term organically popped up again encapsulating both a nod to cubism’s basic modernist geometry but also the aforementioned commercial strategies and politics of display that both of us have investigated in our respective practices.

Bruno: We looked at Autokomanda’s rooms and realised how square they were. We drew a perimeter around them and superimposed a ‘false’ ‘cubism’ that inspired a train of thoughts – cubism, cube, square, height, horizon, perception, reception, consumerism, consumption, neck, neckline. That’s how we ended up with “room-size collars.” And given their scale they also resemble prototypes for guillotines.

Your installation uses the neck, asphyxiation and beheading, as a metaphor for boundaries, but also for standards. Does designing “for the human” still make sense in a world where the very idea of the “human” keeps shifting?

Bruno: The “human” in question has always been a contested generalisation because it is built on the image of a dominant majority. In my collaboration with Anna-Sophie, the human body is a strict scaling device, prompting an exaggeration of an ideal. It’s imposing and anachronistic. And it’s awkward. Unless you are approximately 1,75m tall like both of us, your neck will not pass through the space we left open. So it becomes evident that the very idea of the “human” has the capacity to alienate humans.

Anna: I would emphatically insist that we live in societies where the human body is the very material location – the literal body politics – of life, meaning and love as much as violence, deprivation and hurt – regardless of how speculatively altered our notion of the human may be.

How do you perceive the relationship between “ornament” and “weapon” in contemporary spatial design? Where does aesthetics end and control begin?

Bruno: Ornaments are aestheticised extensions of political projects. They embody codes for users to apply in their everyday lives. So the ornamental is less like a ‘weapon’ with a clear line of offense, and more like a ‘program’ that directs you how to move, think, and act.

Anna: The two cities I am most familiar with are Vienna and New York. While the first could still be described as a classical social welfare state city endowed with one of the most ubiquitous as well as fully city owned public housing projects, the second is the result of late stage North American capitalism. And while I am not interested to flush out the concrete nuances here, I would say as a benchmark ornament tends proportionally to be weaponized the more privatized a space or a city becomes. That said, even the most devious city planning device – a famous one being the metal dividers on park benches to prevent stretched out bodies from sleeping – can be reclaimed by usage and be redirected towards the ornamental by way of atrophy or destruction.

Your work plays with symbols that carry institutional weight (like the no smoking sign). Can art dismantle these symbols, or can it only redirect their power?

Anna: I should be frank: I don’t believe art dismantles symbols or redirects power and I do not attempt such operations with my art. What the don’t smoke symbol meant to me when I first used it, what attracted me, was the many conflicting aspects it encapsulated. First, smoking as a cultural technique laced with meaning by one of the most powerful advertising industries but also a simple symbol of visceral, oral pleasure. Sexiness. Then, the conflicting institutional parties: those who want to prevent smoking in certain places and their reasons, workplace safety advocates as well as health care providers and those who insist, in a Mark Fisherian sense, on a person’s right to a place outside their private home where to indulge in the freedom of an albeit dangerous pleasure. In my mind the person wearing the don’t smoke dress always naturally smoked.

Bruno: I don’t think Art can do anything other than be an expressive display of ideologies. That means that artistic production is usually expected to conform (to propagate the status quo) or confront (to go against, to be anti-) prevalent tendencies. The most exciting event is when someone does something absolutely deceptive. Deception is total opacity, so we can’t even tell if it’s dismantling or redirecting anything. It hacks symbols and signification to an undefined end, while its direction is strongly felt. A movement like that usually pisses off everyone and nobody wants to record it (write it into History).

When creating an exhibition, do you imagine an “average” visitor? Is that even a question that interests you — or do you reject the idea of universality altogether?

Anna: I do not reject universality but I conceive of it, philosophically speaking – as an approximation that is rooted in a shared notion of the human. However I do not imagine average visitors. I make my work knowing that it can convey more than simply the sum total of thoughts I have when thinking it up. That is what good art can do, “be something more”. At the same time, I also understand art to be a specific language, that should not be confused with an attempt to be the most easily read or communicated, like an international toilet sign.

Bruno: I picture only myself as that visitor. This motivates me to imagine exhibitions that can challenge all my senses. I understand exhibition-making as a simulation of a polity. Whether symbolic or not, they hinge on experiences of inclusion and exclusion that define one’s (dis)placement in the world.

Your work makes literal, physical contact with the body. How do you imagine the viewer’s emotional response to the installation? Are you aiming for discomfort, recognition, identification?

Bruno: I’ll be very pleased to see the viewer trying to match their neckline with ours.

Anna: This particular collaborative installation at Autokomanda is a rare instance for my work in which physical contact is possible, but it’s not what I am most interested in. I see the two collar pieces as visual-spatial that is to say formal interventions. The fact that a visitor passes through the gap in the custom built shelving units is fun and I am excited about it, but it’s not a recurring theme for me thus far. On the contrary, I am always supremely suspicious of participatory situations in the exhibition space. There is a theatricality in it that I am often not sure about.

Between drawing and dressing, do you see a parallel in the idea of the “pattern” as a method of control?

Anna: Any standardization has the potential of overwriting the specific instance, the exception, the individual.

Bruno: I would like to add that standardization enforces consensus.

How do you relate to standards — are you fascinated by them, frustrated, or both? Is the Yugoslav Standard for you a utopia, an irony, or something in between?

Bruno: I don’t think I can have feelings about ‘standards.’ As a dressmaker I will always depart from a preexisting form. I either drape a piece of fabric on a Body, or manipulate industrial clothing patterns. But what I enjoy the most is the making process, because to make a new form I must deviate from conventions set out by the old one.

Anna: From the vantage point of 2025 I have the great liberty to look at concepts like the Yugoslav Standard as a historic model. It is therefore not relevant whether they were functioning utopias or failed inhibitions, ethical or violent. In my work as an artist, I behave more sociologically: I study such concepts with strong visual representations as culminations of political desires, hopes and delusions.

Is it possible to create a space that is both inclusive and politically subversive? What would that look like, in your terms?

Anna: I would think that such a space cannot be created by one person alone but that it springs up where people gather with a common concern. However, that is the space of political action that I personally do not confuse with showing art.

Bruno: I see inclusivity as the end of subversion, which is not a bad thing per se: if we achieve a truly inclusive state where our livelihoods are fully supported, why would you want to subvert it? That’s why I believe no exciting contemporary culture is being produced in strong welfare states because there’s no urgency there. There’s no contrast, no paradoxes to be synthesised. But are we close to reaching such space? Right now, liberal circles in Central Europe are struggling to align themselves with their liberal ideals because inclusion has never felt so exclusionary.

What is luxury to you today — rarity, autonomy, silence, or something that still needs to be redefined?

Anna: I think autonomy.

Bruno: Real Luxury is having access. True Luxury is possessing Power which no one does.

Photo: Katarina Šoškić

The project has been generously supported by BMKOES Austria, Austrian Cultural Forum in Belgrade and The Embassy of Kingdom of the Netherlands in Serbia.