The changing view of sex workers through popular culture

From saving the disgraced woman to her emancipation

ANĐELA VIDOVIĆApril 14, 2025

From saving the disgraced woman to her emancipation

ANĐELA VIDOVIĆApril 14, 2025

For twenty years of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, we follow the female detectives as they investigate brutal sex crimes. The victims come from all walks of life, but sex workers are often killed off early or portrayed as unreliable witnesses on the streets. These women face complex challenges, and their rights didn’t start to be recognized until the late 70s and early 80s.

As German veteran and activist Stephanie Klee points out in interviews, we’re used to the negative portrayal of sex workers in the media, as it’s typically the only image that’s offered. The violence we hear so much about, she believes, is a product of our own mindset and the image we create. According to Klee, prostitution isn’t the sale of a body—it’s the sale of a service, and it’s a personal choice. ‘There’s no such thing as love,’ she says, though life might unfold like a movie script, starting with a romance with a client.

The way sex workers are portrayed in film and television has evolved along with changing social dynamics. From rescuing a disgraced – ‘fallen’ woman to her full emancipation in American cinema, to complex, mysterious heroines in European films, we’ve seen a range of interpretations. But perhaps the biggest shift has been in public discourse. The realism of how a particular social group is portrayed now matters more than the personal experience of the film itself. The media’s influence is so strong that it drives broader social change, shaping our perception of sex workers and their place in society.

Belle de Jour (1976.), Getty Images

In such a progressive social climate, the iconic American journalist Gay Talese could only have dreamed of when he published his book on the sexual revolution, Thy Neighbor’s Wife (1980). Talese wasn’t just an observer; he actively explored and indulged in the world of massage parlors and nudist colonies, questioning how sexuality reshaped society’s moral codes. But despite the advances of feminism, American society remained under the strong influence of religious institutions. Unsurprisingly, his book was a commercial disaster. Writing about Hugh Hefner, for instance, nearly cost him his marriage and career.

Yet, social changes unfolded at such a rapid pace that those once labeled as public enemies became glamorous millionaires overnight. Canadian theorist and writer Lauren Kirshner captures this shift in her book Sex Work in Popular Culture (2024), highlighting capitalism’s many pitfalls and the longstanding stereotypes that have shaped the portrayal of sex workers in American films, TV series, and documentaries.

Fortunately, there are exceptions—films like Klute (1971) and Pretty Woman (1990). In Klute, Jane Fonda undergoes an extraordinary transformation from the campy sci-fi heroine Barbarella into Bree, a complex, intelligent sex worker. Sitting on a psychotherapist’s couch, Bree is everything her cinematic predecessors were not—self-aware, introspective, and emotionally rich. Yet, in a moment of raw vulnerability, she utters a line that encapsulates the paradox of her profession: being a call girl means maintaining only the illusion of control.

Julia Roberts with Vivian continues the series of characters best described by the phrase “tart with a heart,” those who easily get under your skin. She has a juicy sense of humor, practical intelligence that tells her—don’t trust when things are going well with someone to avoid getting hurt. Yes, it’s a fairy tale, probably weak comfort for cynics, but sweet for changing the paradigm of escorts in film. That’s why the ground beneath our feet completely shifts in the 21st century with Mikey Madison as the resourceful, adaptable, and quick-witted Anora. For her, every relationship is a transaction. She isn’t too afraid of being poor, nor is she afraid of spending her whole life as a dancer in a club—what she’s truly afraid of is truly loving someone. The eternal party will be replaced by tears, which have no place when it comes to Mia and Lucia in the second season of White Lotus. They are young, self-sufficient, carefree in colorful clothes, first and foremost friends, here to make us laugh at their wit, but also to cheer for them as they cleverly mess with the system and walk away with the money. They might be too much in the “me & my little bubble” of Generation Z’s mode, maybe completely detached from reality, but that’s exactly why they are so damn entertaining.

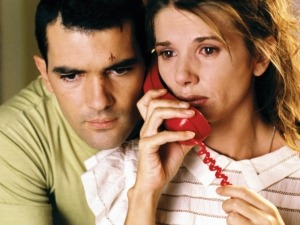

¡Átame! (Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, 1989.)

While the depiction of sex workers in American cinema has visibly changed, the European scene has always been a world of its own. In the 1960s, Sophia Loren in Marriage Italian Style portrayed Filumena, a daytime worker and a lover at night. She embodied the previously unthinkable combination—prostitution, femininity, and motherhood. Her face reflects everything: sadness, anger, worry, and even true happiness. She is unafraid to take matters into her own hands, going as far as faking her death to achieve her goal—making her employer her husband.

Catherine Deneuve in Belle de Jour, also in the same decade, portrays Séverine, a young, mysterious woman who fulfills her own fantasies in a brothel. She clearly separates sexuality from married life. Séverine’s passion is herself. While the husbands in these films are lost, the women rely on wild imagination and instinct.

On the other hand, Almodóvar’s characters, such as the soft porn actress Marina in ¡Átame! or the humorous transsexual prostitute Agrado in All About My Mother find love and support in unlikely places.

On the home ground of Yugoslav cinematography, it’s difficult to find an equivalent, as the films of that time were one of the ways we presented ourselves to others. Depending on the needs, a woman was portrayed as a combatant partisan, a housewife, or of loose morals.

Humanity and complexity have been captured in various ways in the volatile pop cultural field of sex work. This is why we remember and love good films. And it is also why it seems to us that in American portrayals of sex workers, as discussed by Lauren Kirshner, we can more easily count missed opportunities. Immediately, the hit Magic Mike from the 2000s comes to mind, which attempted to explore the position of male strippers. Channing Tatum is the typical protagonist from Hollywood’s dream factory – a roofer by day, a stripper by night. In an attempt to break a few stereotypes, inevitably, new ones are created, and we end up with a film almost identical to the infamous flop Striptease, where the skin is taut, the biceps firm, and everyone is just waiting to spend on what they love. But capitalism teaches us this, doesn’t it? Position, whether good or bad, is a matter of our own making. If we don’t succeed, we simply haven’t tried hard enough.

The magic of cinematic storytelling, no matter the territory, isn’t so rigid. It’s there to offer us nuances. Whether those are in the dark tones of human nature, as seen in Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, or embodied in real flesh-and-blood heroines like Anora and Severine. Before us lies a full spectrum, not simplistic black-and-white portrayals.