Camp against earthly boredom

Luna Lu explores the iconography of YU camp, kitsch, trash, censorship, and freedom of expression—and why “guilty pleasures” are key to shaping our personal taste and aesthetics.

Luna LuNovember 8, 2024

The story of the “Lepa Brena phenomenon” is far broader than a repertoire of popular songs; in a sense, it’s almost metaphysical, a saga of Yugoslavia, its rich pop culture, and a socialist society of 22 million ready to embrace camp iconography. To people today, it might seem strange to hear that the former Yugoslavia once had a legally regulated system to protect citizens from “trash culture”—essentially a tax on kitsch. This controversial law, intentionally or otherwise, fostered a unique creative climate where artists flirted with the boundaries of kitsch and art, creating what we now recognize as “YU camp.”

Defining camp is nearly impossible without delving into dry theory—and camp is anything but boring. It’s a counterpoint to overthinking; it’s about how you receive content, not the content itself. Exciting, shocking, exaggerated, loud, and self-ironic, camp is extravagance enjoyed with a certain degree of intimate discomfort. It’s a way of pushing your boundaries, a spice that quickens the sensory metabolism. “Guilty pleasures” are crucial to forming one’s taste and aesthetics. People who consciously deprive themselves of any “kitsch joy” often end up dull and preachy—Saturn’s disciples ready to impose their idea of “good taste” as if it were the eleventh commandment.

Somewhere between the desire to censor and regulate, a unique “YU camp” was born. In 1971, at a Congress for Cultural Action in Kragujevac, an initiative to introduce a “Law on Trash Culture” emerged. The Communist Party of Yugoslavia quickly gathered cultural workers, from Nobel prize-winning author Ivo Andrić to actress Milena Dravić, to discuss the idea of using sales tax laws to support works of “special social and cultural value.” Products that a commission deemed culturally worthless were branded as “trash,” making them up to 50% more expensive. The tax revenue collected this way was channeled into budgets for culture, arts, and education. Cultural workers were satisfied with the arrangement.

In theory, it sounded almost perfect. Initially, this law targeted “pulp” literature—popular romance novels, crime fiction, and comics that dominated kiosks in the early 1970s. We, the “children of communism,” grew up on comic book heroes, blissfully unaware of the extra cost. It was a luxury that built our sense of justice and the belief that good should triumph. Magazines like, Politikin Zabavnik, Stripoteka, and Alan Ford were our initiation into a camp worldview.

By the late 1970s, the biggest challenge—and temptation—for the law’s enforcers was the increasingly powerful music industry of the Yugoslav discography. Editorial censorship by record companies, followed by media censorship, became a strange playing field where terms like “art,” “kitsch,” and “trash” blurred.

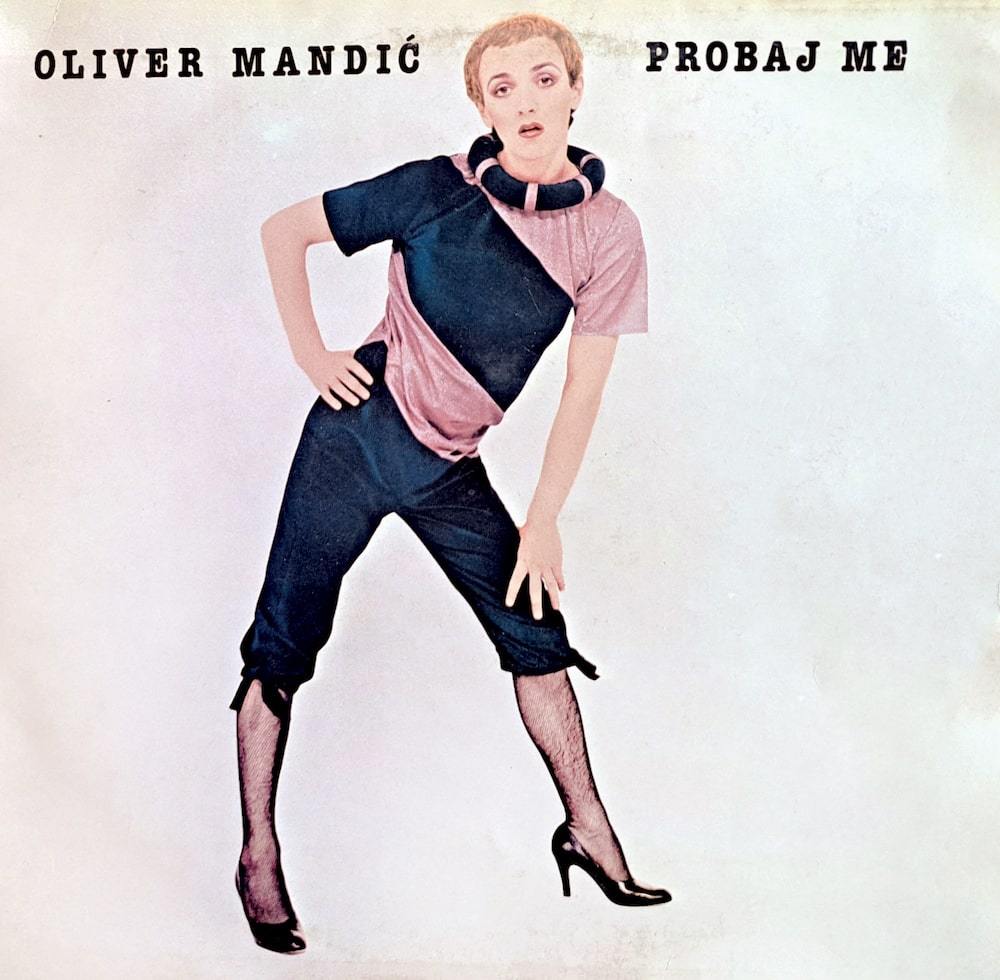

The era also coincided with the arrival of “new wave” music. Censors were, to say the least, confused. How do you tax punk? Its subversion left them bewildered, and in a panic, they branded records by bands like Prljavo Kazalište, Lačni Franz, and VIS Idoli with the “trash” label. Even icons of the neo-romantic camp, such as U Škripcu, were labeled trash—not due to provocative lyrics, but for the eroticism of their album O je cover . Thus, poets like Milan Delčić Delča, dark-humored song-writer Zoran Predin, and folk singer Mica Trofrtaljka ended up in the same category as bands such as Pankrti and Bijelo Dugme.

The attempt to shield Yugoslav youth from the thrilling music scene failed spectacularly, and camp was freed from the bottle. This spirit of music, images, visuals, and styles developed and inspired generations, creating a magnificent history of pop culture—an artistic expression worthy of a place in the Museum of Contemporary Art.

While camp worldwide is often linked to the underground club scene, it rarely became mainstream anywhere like it did in the Balkans, then known as Yugoslavia. Whether people like it or not, that spirit remains part of our collective memory and fuels many wonderful phenomena on today’s scene.

BONUS: YU Camp Markers x 10